Gen X Health: What the hell is happening?

Get-real approaches to coping with anxiety over getting sick and growing older. Plus, why should "staying healthy" be all on me, you, or anyone else?

Growing up Gen X meant growing up fast. Ready or not, you jumped in without supervision, protection or guidance. And then you kinda sorta figured it out using whatever was already inside your own head.

There were no training wheels or adults around helping me learn how to ride a bike. No helmets, sun protection, or soft landings. We had edgy stones underneath our monkey bars at school. The first time I tried a penny flip off the high bar I got a big fat lip that’s left a lumpy bump to this day. The next time I tried a penny flip, and every time after, I landed on my feet.

Whether you learned the hard way or not, you learned whatever seemed to matter in the moment.

The same latchkey-kid feeling is back. I feel pushed into the next phase of life too soon. Ready or not, it’s Gen X’s turn to start getting old and even die. My brother Patrick dying at 52 was a wake-up call for me.

I was reminded of Gen X’s mortality again this past summer after the passing of Shannen Doherty. Seeing the photo shares of her pictured with Beverly Hills, 90210 co-star Luke Perry (who also died in his early 50s) felt generational. Time is running out on timelines not of our choosing. I wrote about that last month:

What’s happening to health?

Because I am one, I’m sure I’m noticing more Gen Xers newly diagnosed or suddenly gone. But, it seems like more than that, and like it’s not only my family with declining generational health. I’m also seeing non-scammy headlines like, “GenX Faces Higher Cancer Rates Than Any Previous Generation” and studies like “US exceptionalism? International trends in midlife mortality.” The uptick seems to be more than my own cognitive bias.

Last month, the American Cancer Society (ACS) published a study about an increased cancer risk for post-boomer generations. The data set they studied extended up to the birth year of 1990. Researchers found 17 of 34 cancers are occurring at higher rates among Gen Xers and millennials than they did for boomers when they were the same age.

Whenever I see scary-sounding statistics like this, I remind myself that while these types of numbers have salience on a public health and policy level, they usually don’t change what I should or shouldn’t already be doing. And then, I go past the headline to the study itself or another trusted source.

Dr. Karen E. Knudsen, CEO of the ACS, summarized the findings in this PBS NewsHour interview:

Dr. Knudsen closes the interview with these reminders:

Adapt a lifestyle and diet known to lower the risk of cancer.

Follow cancer screening guidelines based on your individual risk factors. Age is only one risk factor, so it’s “never too early” to discuss a cancer screening plan with your clinician.

Get signs or symptoms checked out no matter your age (no one is “too young” for cancer).

The ACS estimates that around 40% of cancer occurrences are considered “preventable” because they’re linked to diet and lifestyle. You can find a bar graph of modifiable risk factors in Figure One of this ACS study. Preventing cancer involves the stuff most people know. Avoiding alcohol and following vaccination guidelines for HPV and Hep B are probably the ones I see most overlooked.

Dr. Knudsen reminded not to let fear of bad news keep us from getting screened or checked out. Even if cancer is found, in a growing number of cases, cancer can be treated as a chronic illness that’s managed over years. And the earlier many cancers are caught, the better the outcome.

While many of the types of cancers that are increasing are linked to known lifestyle factors, Dr. Knudsen also pointed out that there “must be something else” in addition to them to explain the overall trendline in their study.

If someone tells you they know exactly what that “something else” might be, especially if they’re selling something, don’t listen. It may be lots of things, including timing, unknowns and individual differences. So I’d rather focus on known modifiable risk factors than buy into unproven claims that may have negligible benefits (if any), aren’t practical to do (or avoid) and may even cause harm.

Fear of getting sick

Fast fixes and easy explainers of how to avoid becoming ill are everywhere as wellness seeps into everyday conversation. The appeal is understandable. Getting sick is scary. Feeling crappy is crappy. But worry alone doesn’t stop anything from happening. And it might make it worse.

I’ve totally been in that Google swirl of misinformation at times in my life, especially vulnerable ones—who hasn’t? And, I’m a sucker for testimonials. Not the pushy, heavy-handed selling kind, but the genuine ones or the ones that seem genuine. And yes, I do know one random person’s experience is not an indicator of what mine might be. But still, I’m human. And the older I get, the more human I feel.

I’ve got my start to a growing “problem” list and my mom’s list is so long it even surprises her doctors. People can live a long time with lots of “problems,” sometimes surprisingly well.

Undercurrents from the past

Modern medicine is far from perfect, is often inaccessible and (even under ideal circumstances) can’t address every need or problem. Still, it saves lives, boosts the odds for better health, and helps many people live longer and better.

I work in a traditional healthcare setting and follow evidence-based health guidance for myself and kids. Of course, that depends on having usable health insurance and meaningful access. Even with that, not everyone in my life and family feels this way. But I don’t feel like we’re on different “sides.”

Aside from the entrepreneurs in attention, money, or conflict is everyone else—people trying to get by or get well while figuring out who or what to trust for themselves and loved ones. Respect and empathy should be shared with everyone when it comes to their personal health decisions and bodies.

Not everyone thinks about health decisions the same way. And a person’s health decisions can change over time. I’ve been all over the map at different points in life. That makes me more curious about other people. Because when feelings and past experiences are shared and acknowledged, it seems easier (or at least possible) to have forward-moving conversations.

Crisco and a cloud of smoke

It’s mind-boggling to think about all the ways modern medicine has been life-improving, saving and extending just among people I know, myself included. But I can also understand why some people feel mistrustful of health-related information. Everyone and every family has stories. In my own, I hear so many.

My grandma worked in a raincoat factory while pregnant. No one told her that might not be be safe. Everything was “safe” unless something big and bad happened, and the specific outcome was unequivocally linked to the specific cause. Many people I know feel some sense of violation or being “lied” to.

My brother’s childhood friend was born without arms because his mom was prescribed thalidomide during pregnancy for morning sickness. People remember tragic public health errors like that because it wasn’t that long ago. And it’s human nature for those to be remembered the most and longest.

My mom will always bring up the margarine-butter debacle. “They say one thing, and then they say the opposite,” she says.

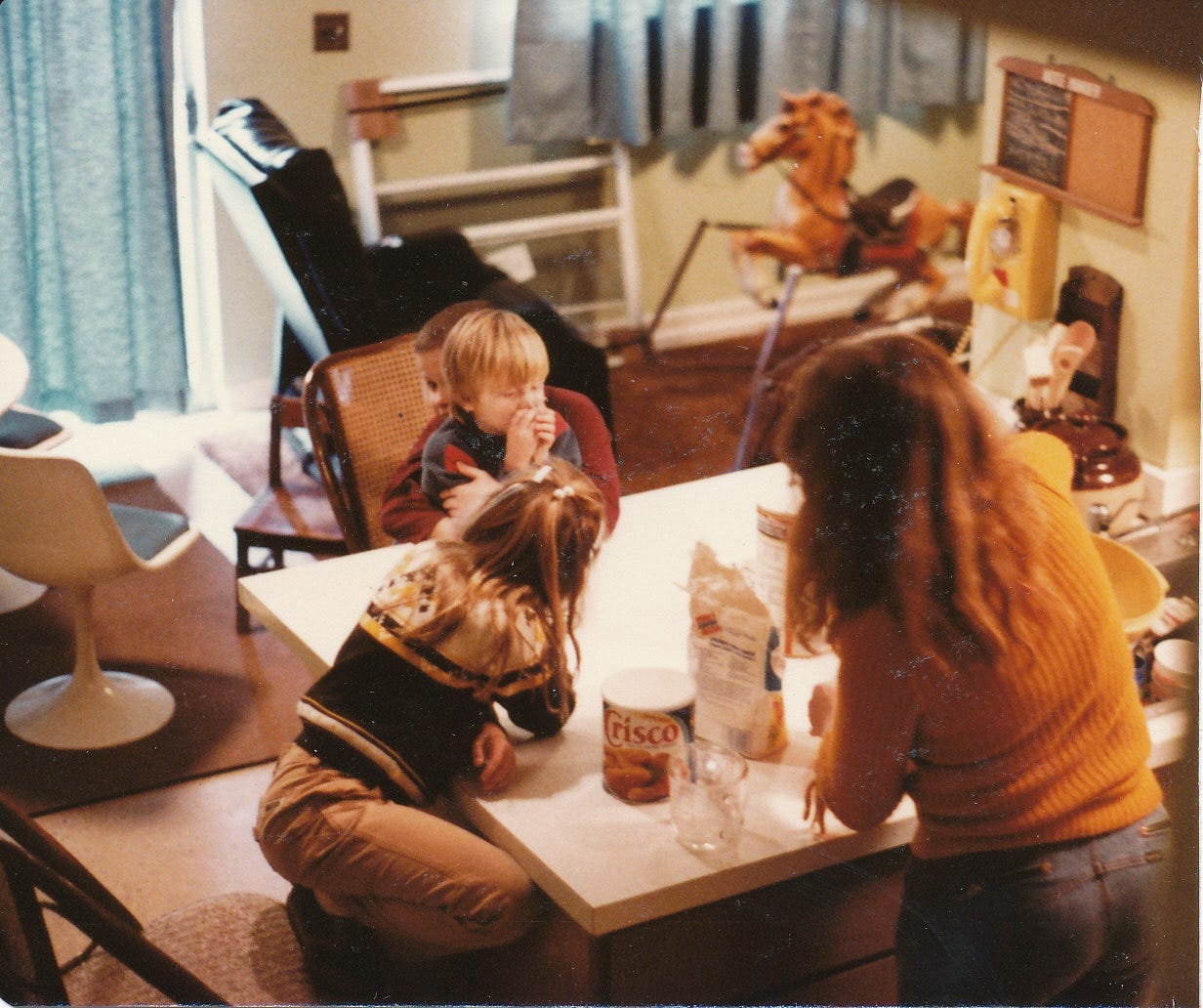

Crisco was the good stuff when my mom was growing up. The stuff at the store. The stuff her family couldn’t afford. Lard was given out with free food for families in need. My mom felt good buying Crisco and giving me and my brothers the good stuff. She still talks about the prize-winning pie crusts she created with original Crisco.

Around the time word spread her Crisco was bad, lots of other good-turned-bad (or bad-turned-good) things were being reported—at an increasing pace. Meanwhile, “trusted” sources of information were splintering into websites and cable outlets, which increasingly reported with quippy, punchy tones that hit very differently depending on whether you related to the brand—or on how you imagined them perceiving you or someone close to you.

It felt dizzying for my mom, and she didn’t know what to believe anymore. She always asks lots of questions and is skeptical because she’s learned to be. I share information with her when she asks, but I can’t tell her what to do.

Seriously though, that Crisco mistake—saying trans fats were “healthier” because they were free from cholesterol—did cause harm to people’s health. In 2006, researchers estimated that removing trans fats from diets could prevent 250,000 heart attacks in the U.S.—in one year alone.

Mistakes happen. New information comes about, and that’s a good thing. The frustrating part is the lag time between when a problem or error is first known and when corrective action is taken. Or when common sense is ignored.

For me, 1986 is when I first experienced that feeling of mistrust. A big public health announcement came.

After growing up in fumes of cigarette and cigar smoke, a report from the Surgeon General titled “The Health Consequences of Involuntary Smoking” declared that “it is now clear that disease risk due to the inhalation of tobacco smoke is not limited to the individual who is smoking, but can extend to those who inhale tobacco smoke emitted into the air.”

This “insightful” finding came after a study that began—in 1972. Even as a tween, I was like, “Duh.” What non-smoking person wouldn’t somehow know that smoky air wasn’t good for them?—even more so for the many people like my husband with asthma or other lung diseases. Of course, the details needed to be researched in-depth, but why did it take so long to state the obvious and spare countless lives?

Over the next decade, the second-hand smoke announcement led to limits on indoor smoking—and that caused more people to quit (or cut down), more than anything before. But it was too late for the two people I knew of who were dying of lung cancer in 1986.

A few days before the year began, we moved into an early 1960s split-level just after my mom and stepdad were married. Every surface in the house was saturated with nicotine stains that penetrated layers of wallpaper on walls (and ceilings) and inches of shag on the floors, including the plushest Cookie Monster blue pile in the living-dining room—the floor that had a moonwalk bouncy feel.

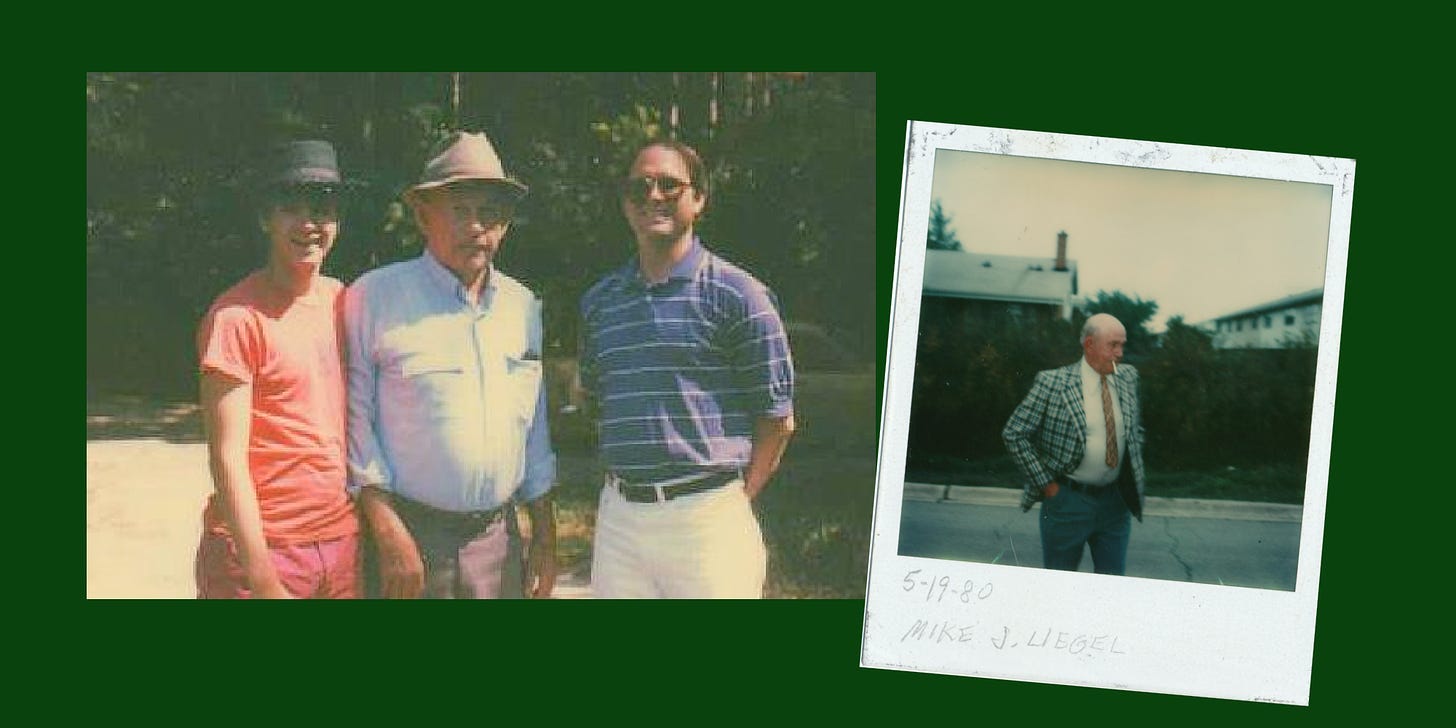

Just before moving in, we met the previous homeowner, a sweet older woman not that much older than my new stepdad. She gracefully explained that she had lung cancer and was moving to Florida to spend her final months. She was the first person I’d ever talked to who knew they were dying. Soon after, I found out my grandpa Mike had lung cancer.

Sitting in the backseat while Dad drove Grandpa to an oncology appointment, my dad bluntly brought up the elephant in the room I was still trying to accept. I was horrified by the back-and-forth banter that ensued between my dad and grandpa, especially the dark humor. How could they joke about dying? Isn’t death the worst thing that could happen?

But somehow, Grandpa seemed comforted by the conversation with his oldest son. I didn’t understand then. I get it now. Dad was talking about death as a normal part of life. And he was talking to Grandpa like normal too, the same way they always joked around. Grandpa seemed to feel better, less alone and more respected by Dad treating him like he was a real living person still here. Grandpa was just getting ready to go to the same somewhere we’re all going.

No matter how against smoking I was as a tween, I still ended up smoking from 1988 to 1994. I was copying the behavior I saw, including the thin-at-all-costs mentality of the time. But also, I liked smoking. Not the first time I tried smoking when my friends and I bought a pack in a bowling alley vending machine.

Soon, I found the coolness and thinness of menthol Virginia Slims, which made me cool and thin too. Then I learned their nickname. But by that time I was hooked, so I switched to Marlboro Lights with their lovely, rich harvest gold color package. That color still draws me back to the goodness and something more feeling of being a kid.

I might still probably be smoking if I wasn’t pushed outside during work or college when the smoking lounges went away.

Humans are meant to need other people. So why is it so hard to ask for help? And why is it even harder to find it?

The toll of getting sick

Most people I know aren’t afraid of dying as much as they’re afraid of getting sick and the financial, emotional, and life-disrupting toll it would take. Needing help might be normal, but finding it—no matter how great the need—isn’t easy. And anyone can shift into that category from one day to the next.

I’m 50, so according to the Social Security Administration’s Actuary Life table, I’m expected to live for another 32 years. If I were born male, that number would be 28 years. Health years, however, are much harder to measure, predict and plan for.

Although there’s a desire for neat storylines with first-next-last sequences and clear endings, illness doesn’t usually work that way. There may be lots of uncertainty, unknowns and unexpected outcomes (sometimes for the better). Meanwhile, ordinary life goes on. The grind is tiresome even when you don’t feel like you have a reason for it to be. It keeps on and piles up, whether you feel ready to participate in it or not.

Sick while you’re sandwiched

My mom was a sandwiched caregiver, taking care of her mom, her husband with late-stage liver disease, and her three teenagers—while working full-time plus. As a commissioned recruiter, after-office hours meant conversations with candidates over her kitchen phone while doing whatever tasks her curly cord could stretch to.

My stepdad Gene couldn’t work and had no health insurance or pension. It doesn’t make sense why it’s harder for someone in midlife to get help than someone in retirement. If you need help, you need help. Why should it matter your age?

The way that financial hardship compounds the stress of illness is nothing but heartbreaking. I remember seeing the mix of guilt and grief—Gene anguishing about the medical bills he’d leave behind and Mom wanting him have the best chance to live better and die with dignity. Mom ended up in medical bankruptcy after Gene died, which itself (grieving aside) was a long, harrowing process.

The stories that don’t get discussed enough is what it’s like to face serious illness when you’re sandwiched between generations that both need your physical and financial help—especially for people who are unpartnered or have few resources and reliable support. More people experiencing cancer in midlife also means more kids living with someone seriously ill.

Patrick lived with our grandparents during Grandpa’s illness and was 17 when he died. Patrick was also made a caregiver, bringing a unique kind of trauma. I lived with our mom during our stepdad’s illness and was 17 when he died. Being a teen can already feel isolating and depressing just because.

Illness and death were pervasive in movies and on TV, but there was no space in the culture to talk about day-to-day living through it. Having more comfort and openness to treat death and illness as the normal part of life it is, seems important for helping everyone feel included.

Community care matters

Even when there’s a diagnosis in a chart or a cause of death on a certificate, there’s a whole story behind it that even family and friends might not know. Further mystifying is how an individual’s story is interwoven into their community’s.

Everything I’ve ever seen from anyone I’ve ever known is that the preventable side of illness—diet, lifestyle, health-related behaviors—seems more about community health and mental health than an individual’s “choices.”

So why does “staying healthy” feel like it’s all on me, you or any one single person? And how is that even possible? To start, many health outcomes aren’t entirely (or even partially) preventable. And even when there is a preventable cause, I can’t undo the irreversible changes in my body I’ve already accumulated over 50 years of real-world living, which of course included some regrettable “choices.”

“Social determinants of health” are finally beginning to be formally recognized as a real thing. Knowing is a necessary start. Now the challenge is to make actionable changes.

Final thoughts

As I grow older, I keep learning how important understanding the feeling side is to any conflict, decision or outcome. Fighting with facts never panned out well in my real-life relationships. And I’m much more careful and nuanced talking about facts in general.

Nuance might not “sell” well, but it can be explained in a way that’s helpful and appreciated, ideally by a wide range of messengers. And ideally engaging—but without a quippy punchiness that oversimplifies and divides. Also, I don’t want to become so loyal to any facts that if new contradicting information comes about I can’t consider it and always be ready to let go and move on.

Gen Xers may be too young to die, but maybe we’re ready to get old, figuring it out on the fly while staying young at heart, just like we’ve always done.

Decades later, I still have cravings for cigarettes. This CDC website provides links to resources and treatment options for anyone interested in quitting. Though still not easy, having support might help.

Related recs:

In “Health insurance in America is a gamble,”

writes about the dysfunction—and resulting anxiety—of getting (and staying) insured.I started reading The Anatomy of Deception. Dr.

’s thorough research, including interviews, helps explain the relationship between medical mistrust and political divisions. Importantly, she offers thoughts and ideas on “what to do” to change this dangerous dynamic.Next post: My body at 50 feels 50—and that’s OK. How I'm thinking about health and well-being after 50.

You have no idea... I have been thinking "what's going on..." for a while now! This hits deeply for me, Daphne. Today marks the anniversary of my brother's birthday, one year after he left at 59 years old. He never got screened for colon cancer and that rapidly attached to his liver. It was a tough ending that lasted 3 months too long. I miss him AND your timely article hits home for me since I follow evidence-based health guidance for myself and have been for years. I worry too much about health, having seen him suffer and my dad as well. I appreciate this and no, it shouldn't be all on us. This is America for now. Thank you. p.s. my mom wanted to keep that wallpaper on her house's walls until the very end! :)

There's so much here in this newsletter, Daphne. Thank you. You also got me thinking about orangey-brown wallpaper. I think you're onto something!