Marriage and Scandal in the Pre-Boomer Olden Days

Forget happily ever after. Some marriages were heart-wrenching prison sentences. Staying avoided scandal. But some scandals might be worth the risk.

Could online dating change civilization? I heard this lofty question asked years ago. To be fair, the expansion of dating prospects to a world-wide-web scale was difficult to fully comprehend at first. But there’s a weird assumption that new trends will always continue along at the same accelerated pace.

Then comes a new generation. “That’s so millennial” I hear the Gen Zers in my life saying — and this attitude might be showing up in their generation’s emerging dating preferences. According to a 2023 Harris poll, Gen Zers are shifting away from online dating. Some 44 percent of respondents “would rather clean the toilet than go on another online date.”

So what’s Gen Z into? They’re more likely to date a friend or someone they already know, suggests a 2023 American Perspectives Survey. Maybe that’s why Bumble BFF is becoming so popular. It’s easier to go straight to getting together IRL. And who knows? Maybe that friend will become something more.

Early-GenX and Boomer dating circles were similar — school, work, friend groups. Still common places to meet today, but dreadfully limiting when those were your only options. That’s why teens used to want to drive so badly — to look for someone from somewhere else.

Online or in-person, modern dating experiences sure beat the pre-Boomer olden days — especially if you were a woman. Your lot in life was determined by your husband. And choices were nearly non-existent.

Being at a crossroads between young and old, I’m reminded of my place in a long, continuous line of some things that change and some that don’t. Feeling more connected to the women before me brings a feeling of fullness, but also confusion. Thinking — lots of thinking — then writing, is the only thing I’ve found to help sort it all out so I can feel settled again.

This is a story about the women in my family born a century or more ago. The stories here are based on ones I heard growing up. But they’re only pieces of a bigger picture I’ll never fully know — obvious, but still important to say.

It’s also important to acknowledge that my family’s experience was shaped by being white, which had relative advantages and protections. Hard as their lives were, I can only imagine how much harder they could’ve been.

Family are the people you carry into your own life in some way or another. I think it’s helpful to understand that impact. And sometimes learning someone else’s journey can help you figure out your own. That’s been true for me.

Their names were Nilla and Safronia

My mom’s grandmas had shit “choices,” shit marriages, and tragic lives. One emigrated alone from Norway and ended up marrying an abusive man. Why did everyone in town gossip about it, but nobody did anything about it? Recently, my mom was sorting old pictures while I was visiting and she came across her grandma’s death announcement from the 1950s — it didn’t even include her name. My great grandma was listed as Mrs. (Husband's Name). Her name was Nilla.

My mom’s maternal grandma married her mom’s 20-year-old cousin when she was 12. That’s right 12. She had her first of six babies — my grandma — at 15. Then, in her 20s, my great grandfather threw her out on the street when she got pregnant by a “well-to-do” man she was making a suit for. Even her own parents wouldn’t take her in, though they did take her baby.

My grandma told me about the last time she saw her mom, having sex with an unknown man out in the woods and then disappearing with him on horseback. Her mom died a few years later at 28. Her name was Safronia.

My grandma Odessa

Things weren’t much better for my grandma. Her dad made a living selling snakeroot and peanuts. He’d lost his leg in his 20s working as a log roller, and later spent time in jail for bootlegging. When my grandma was still a teen, her dad lost their home. It was 1940 and the government needed the land to build Fort Polk.

My grandma, barely literate, worked in the commissary by day and ended up dancing on tabletops for servicemen by night. She married one, had a kid, and moved in with his family while he was serving. After my grandma moved with her in-laws from Louisiana to Wisconsin, she ended up on the street, when her husband stopped sending her money.

My widowed grandpa took my grandma and her son in as paid help. Soon after they married. She took care of the farm animals, worked in the tobacco fields, and kept house in a home without running water. The marriage worked out well for my grandpa. Free help, and he still got to keep his mistress on the side, or in the middle, or wherever he damn well wanted her to be.

Eventually, my grandma couldn’t take it anymore and left my grandpa. She took the pig money and gave it to a lawyer who promised her she’d get custody of her kids. My grandma lost everything. And my grandpa got to tell her story, rip up her letters, and not allow her name to be said again. Her name was Odessa.

There were no backsies to anything in life. Nor sympathy. You made your bed, you slept in it, you had no choice.

My grandma Marie

My grandma Marie from my dad’s side grew up a whole world of stability away. She was my only grandparent who went to high school. The only one who lived a long life, making it to almost 94. My other grandparents died at 54, 66, and 71. But still, her life wasn’t easy. And her marriage choices were limited too.

She turned 18 in 1942, during a war when any young man who could go went. The pool of young men in her hometown with fewer than a thousand people grew even smaller.

It also didn’t help that she completely ruled out dating anyone outside of Plain — a town mostly filled with Catholic families who originated from the same Bohemian-Bavarian border region near Waldmünchen, Germany. (The concept of pedigree collapse was always easy to understand because almost everyone was a recent cousin.)

My grandma told me she hid upstairs when a young man from another town came knocking on her parents’ door after seeing her at a local dance. Instead, she chose the “funny one” who delivered milk to her family. The one who dropped out of school in junior high after his mom died of cancer. The one who worked in his brother’s cheese factory and had a familiar family name.

It’s strange how random little things can determine life-changing decisions. Like how my mom — a foster kid “ward of the state” — chose work over college because she was afraid of not having enough money to buy lotion for her very dry skin. Or how a few of my grandpa’s jokes convinced my grandma that he was the one — ‘til death do they part.

My grandparents were like a Catholic, rural Midwest version of Archie and Edith. My grandma was always cleaning or cooking and my grandpa returned from work each evening wearing a working class button-up shirt and polyester pants.

Married in 1946, my grandma had a baby every year or two after my grandpa returned home from serving overseas. They started out in a rented room and then bought a house. Early on, they lived on one floor and rented out the other.

My grandma chose the fancy, turn-of-century Craftsman. Kitty-corner from a tavern and a butcher in the front. With a construction company in the back. She soon regretted the choice, which turned out to be a big, loud mistake … just like her marriage.

“Well you married him,” my grandma’s mom told her when she voiced her dissatisfaction with married life. There were no backsies to anything in life. Nor sympathy. You made your bed, you slept in it, you had no choice.

My grandparents stayed together. But I always understood why they slept in separate bedrooms, on separate floors. Distance was better than drama.

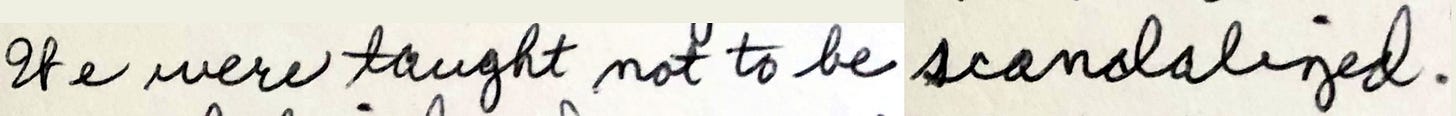

“We were taught not to be scandalized” felt deeply disturbing, deep in my bones. I felt the two lineages of women in me come to a crashing point.

A stayer, avoiding scandal. And a leaver, being scandalized.

Haunting words

My grandma Marie’s been on my mind after coming across a card she wrote. In the middle of a paragraph talking about her 1930s childhood was the sentence: “We were taught not to be scandalized.”

I know there’s some precise theological meaning to those words. I could vaguely hear my conservative Catholic brother explaining it in my head. I gave up having IRL dead-end debates with him after reading High Conflict by

. But after having so many, the start of hypothetical ones occasionally pop up in my head. I wasn’t thinking about a religious perspective anyways. And probably wouldn’t have been able to understand one — the words only sounded wrong to me.“We were taught not to be scandalized” felt deeply disturbing, deep in my bones. I felt the two lineages of women in me come to a crashing point. A stayer, avoiding scandal. And a leaver, being scandalized. I also knew those words explained something important about my grandma Marie’s life, and maybe my own. She was the relative I was told I was the most like. And I always knew that wasn’t necessarily a compliment.

My mom says she could tell I was like my grandma Marie even as a baby. Maybe that’s why she chose Bernadette for my middle name. “Your mother got my name mixed up,” my grandma used to tell me, because technically our middle names didn’t match. But I always knew — and was thankful — my mom chose Bernadette over Bernadine. As I grew older, the comparisons with my grandma continued. Too picky, too stubborn, too high-strung — just too much in general.

Now I can feel my grandma Marie in me. As I look down at my nearly 50-year-old hands, seeing my thinning skin not fully concealing the branch-like veins underneath. Or as I see the reflected new lines forming on my similarly long-shaped, too-serious face — giving away every dissatisfaction that’s been on my mind for the past decade. My paralleled life is catching up to places I never imagined I’d reach when I was a little kid and first learned what old looked like by watching her.

The myth of perfect

Like my grandma Marie, I’ve lived my adult life following rules, avoiding scandal. I never wanted to end up like my mom, or her mom. I wanted security and status. I became a Talbots-dressed Catholic mom living in an immaculate colonial success home with everything perfectly placed. I was that version of myself five years ago when my family gathered in my grandma’s house to celebrate her first birthday shortly after she died, an event that felt celebratory for a long-lived life.

Just after singing Happy Birthday, the conversation shifted to high school years. And soon someone brought up my “badass” scandalized time of life. As if it were funny. Wanting me to join in and shame that young version of myself. The time of my life I mostly forgot about and was glad few knew about. A time when I was slut-labeled like the women on my mom’s side. But also a time I was crazy-labeled like my grandma Marie.

Like her, I was the one in the family who was unwillingly put in a psychiatric hospital. We both became unhinged trying to meet bullshit, unrealistic expectations during times of internal hormonal change. For me, it was as an overwhelmed, runaway 16-year-old. For her, it was as an overwhelmed mom after her sixth was born. My grandma never talked to me about it, but I can only imagine that like me, she left with more trauma, without getting any real help. But I also imagine her 1950s stay was much worse.

I’m not like other girls

The good thing about my experience happening at a much younger age, is that I factored my mental health into many choices during early adulthood — choosing a sensitive partner; spacing my pregnancies further apart; having a career outlet for my fastidious tendencies.

Choices that were only possible because I had privileges that none of the women before me had: access and acceptance for birth control; growing emotional awareness in the Oprah age; feeling safe enough to be able to think on a longer-term basis.

I’ve spent the past few years trying to integrate both lineages of women. And part of me wonders if there’s some sort of internalized misogyny happening on a biological level, as the two lineages on the 23rd chromosome fight for control of expression. One X-chromosome directly from my dad’s mom, and one from my mom’s side. Is that why I always feel torn inside? In truth, my life has always paralleled both my mom and dad’s mom, which meant doing a 180 always felt possible.

While reading through my old diaries this past year, one of the saddest lines I came across was this: “I’ve been slutty before, but she’s the ultimate slut.” At 16, I was accepting a label for myself no one deserves, and then placing it on someone else, while trying to position myself above her. I’m not like other girls.

Internalized misogyny is so shitty. But that’s what fear of being scandalized causes. And that’s one reason why “we were taught not to be scandalized” bothered me so much.

After someone dies, it can take years to process the loss. Years to sort through what’s left behind, the physical and emotional. And years to figure out what to hold on to, and what to leave behind.

Risks worth taking

My grandma Odessa’s whole life had been scandalized. I couldn’t pretend not to know what she went through. She opened up and shared her pain with me. She’d been married four times. Lost all her teeth at 28 and lost all her kids at 38. She served time in jail for petty crime while pregnant. And she carried the weight of a large benign growth that began in her early 30s. I used to explain to my friends: “No it’s not a baby; it’s a non-cancerous tumor.” And since then I’ve wondered: Was that from working in a raincoat factory?

But one story my grandma Odessa told me stuck with me more than almost any other in my life. When my grandma’s dad went to jail, she was sent to stay with her uncle’s family. Her school was in permanent disrepair so she worked in the fields to earn her keep. Her uncle repeatedly raped her. She tried to get help and told her aunt. After she did, her uncle took her in the barn and beat her.

I’ll never forget my grandma’s face, or the pain I felt for her, or the disgust in how evil a person could be, or the not understanding why bad things are allowed to happen. But I know she confided in me because she wanted me to know it’s okay to talk about bad things.

My grandma wanted me to know: what happens to you, and what people do to you, are not who you are.

After someone dies, it can take years to process the loss. Years to sort through what’s left behind, the physical and emotional. And years to figure out what to hold on to, and what to leave behind.

Here’s what I’m thinking now: I don’t want to live a life so worried about what people think that I become someone I don’t even like. I’d rather live fewer years, have fewer things, and find fewer comforts than turn my back on something important, just to avoid risking scandal, or seeing something I don’t want to see. Some risks are worth taking.

What’s next?

Shortly before my grandma Odessa died, she had the large tumor that had been growing for four decades removed. Due to its large size, her belly button was also removed, leaving a permanent hole. When she visited, I’d pour hydrogen peroxide into her navel hole when changing her bandage.

My grandma could've had the tumor removed years earlier, leaving her body intact. But she didn’t, because she didn’t trust doctors. And her early life experiences, including traumatic childbirth, explained this. Access to healthcare is incredibly important, but access alone is never enough.

For my next interview, I’m excited to talk with Medium writer Soojin Jun. She’s co-founder of Patients for Patient Safety US and editor of I am Cheese. She calls herself a “dreamer of empathetic and humble healthcare.” She a “caregiver turned pharmacist” and an advocate of trauma-informed care. I’m SO looking forward to learning from her and sharing her insight with others!

The strangeness of being in the middle of your mom and her mother-in-law

Mother-in-law and daughter-in-law relationships are complicated, even more so after divorce. I was stuck in the middle — between my mom and dad’s mom — for decades. I felt fragmented and wondered: Why are the women who stay sometimes the first to judge? Why do they set the standards other women are compared to?

My Grandma Odessa

My grandma had a stillness of one moment, followed by another. And in those moments she shared her stories from long ago, in full color and tell-all style. There were joyful stories that warmed her face into a wrinklier one that smiled – and unbelievably, tragically sad ones when she would pull out her handkerchief hidden in her bosom, to wipe away the tears that followed. But unlike the drama I watched on TV, when bad things happened in her stories, they were barely noticed and life just moved on. No dramatic music, no happy ending, not even a conclusion.

Daphne, I finally had a chance to read this incredibly moving post. Wow. There is just so much here! And yet I want more! I hope you will write more, though I am sure it is hard to share. I really love the lines you've threaded between your grandmothers' lives and your own. These women's stories are riveting and also very painful, because in a way I feel like if we look more closely, the misogyny at the heart is very widespread, probably for most women of these generations. Thank you for sharing.

Thanks Sara for your encouragement! These stories have been in my head and heart a long time. I’m grateful that my family was more open than a lot of other families I know. It’s so sad to imagine all the stories that will never be known. Sharing stories can help because one person’s or one family’s story usually overlaps and connects with lots of people’s. And even though it’s known that misogyny filters down through generations and into the present culture, stories from the “olden days” really help show these connections.

Reading your Substack always brings such joy! After I read your last post, I started thinking about some essays on lighter topics. I still have more difficult stories to write, but I like the idea of keeping a balance. Your writing always inspires me!