AI Word Monsters Eating Us All

AI Authorship and authenticity: Why I finally joined the AI conversation—and how to navigate it with kids

I’m not an AI expert, *top voice*, or anything like that, even on a purported level. This post is for someone who is trying to figure out what to think and wants to hear how another writer or parent in a similar place is handling the AI monster threatening to eat all our words and maybe much more.

Comments of the kind kind are very welcome, and criticism that’s constructive always counts as kind. So if I’m wrong about something, please, please do share. I love hearing other thoughts and perspectives, but also totally get if you’re tired of giving your words away and would rather not.

Decades into the internet age, we’re on the cusp of another massive jump that’ll make the changes seen so far seem like minor bumps.

AI is at a fever pitch, spanning all ages and sectors. It feels consuming or exciting or like a harbinger of horribleness. Aside from people angling themselves as experts in the space or strategizing savings that it’s purported to provide, most people I know fear it and don’t really know what “it” even is (myself included).

Even among skeptics, there’s a growing sense of defeat as they’re succumbing in droves. Are you jumping on the AI bandwagon, and if so, which ones? Do you want to be there? Or do you feel like you need to be on just to hold some sliver of relevance, enough to stay employable and in the game (for now)?

“AI is not going to replace humans, but humans with AI are going to replace humans without AI” — Harvard Business School professor Karim Lakhani

The insufficiency of our human capacity to hold information is undeniable. Some estimates suggest that 90% of data in the world was generated within the past two years. As AI generates more, it’s incomprehensible how quickly that timeframe will shrink. It used to be: here’s a problem, here’s the data, now find a solution. Two heads are better than one, and three or four or more are better still. Sooner or later, something will be solved (at least on paper).

It’s increasingly becoming beyond the scope of human intelligence to find a relevant solution that takes into account the already known knowns and can be delivered within a reasonable timeframe—which today means like now. But even if someone comes up with some smart-sounding solution, how quickly does it sound antiquated when “rapidly evolving” applies to everything yet feels understated in describing the pace of change?

But it’s not just our brain’s limitations to keep up with change, computing capacity, and storage. There’s a growing consensus that humans are fools, unable to get along—even when interests are shared, stakes are high, and solutions are obvious.

So why not hand more over to machines? We’ve already outsourced our memories, connections, and attention, so why not let them take our entire heart-beating bodies? Why not give up all our words? They can tell us what to say, what to write, and even what to think or feel and who to like or love.

“Use your words,” toddlers are told. Learning language begins with finding and taking ownership of your own words. You can keep them in your head or choose to share them or scream them into the void. Writers can sell them or give them away (or “sell” them while giving them away). But now, it feels our words are being taken, or more like stolen, only to be fed to an AI monster that will one day eat us all.

“The longing is too large for one object. It is not aimed—it is ambient. Atmospheric. It asks not for this or that, but for everything. There is no ridding the world of this feeling, so I join it.” — “In defense of longing” by

.

Writing is a place to sit with longing. You can read other people’s words and join them in their longing, which may exist in the same atmospheric ambience as your own. And if you’re 50 and in peri and your longing just so happens to peak around your period, it might even feel uncannily familiar.

I’m already longing for the days when my words were mine and yours were yours. And when you could trust that other people’s words were theirs. The time when you count on at least some parts of the world being measurable and comprehensible—if not by you or me, by somebody in some body.

Longing to write

Anyone can write, even more true with talk-to-text, but few people want to be writers, especially after they try—or after they find out how crappily writers usually get paid.

Plus, most people don’t want to stay stuck in a thought bubble until an idea coalesces and then fuss around with words and syntax in between short bursts of flowing formed sentences that seem spot-on until you read them the third time. And most people don’t desire to have their work picked apart or mind having it handed back with hints on how to make it better or maybe advice to scrap it and start over.

Longing may have led me to writing, but the process itself is what made me want to stay. Because if you don’t like the process, what’s the point?

Letting go and pushing on—that’s being a writer.

When I started writing four years ago, I purposefully wanted to learn the same way my kindergartner was learning to read and write: tinkering time and thinking time, human feedback and support, and mostly 20th-century tools. After two decades of having kids in K-12 school, I still think that’s the best 21st-century way to learn too.

Early on, I moved away from pen and paper. My handwriting’s gone to shit, and I’ve grown too impatient and tired with fine motor tasks. I don’t think it’s just my age. My younger kids don’t like writing by hand either. Handwriting is terribly tedious. Still, it’s exactly how I want my kids to learn to write because I know it’ll also help them write to learn.

A digital writer

When I shifted into medical writing, I moved into Google Workspace and spent long hours immersed in PubMed, basically reading anything recently published that had anything to do with the topic I was covering, along with a mix of older sources that might add perspective. Video and podcasts worked well while washing dishes. Anyone can be a quick study on anything; how cool is that?

As I practiced translating thoughts into words and combining sentences into paragraphs, I also practiced finding ways to back up every fact-based point with linear lines to credible and relevant evidence.

Although time-consuming, I love tracing information through sources and sites, comparing how different publishers and authors cover the same data set, noticing how data are described differently over time even when there are no significant differences in the data. Information is misused and misrepresented. Outdated data gets passed on as new. And many known knowns can’t be found online or explicitly stated in sources—anywhere.

Everything is not online

Most history is never recorded. Few voices are ever heard and unspoken truths don’t get documented or even acknowledged. Art acts as a vessel for carrying and passing on precious knowledge of these kinds—when it’s allowed to.

“Art gives a voice to the voiceless; those in power are fearful of the currents that it can unleash. Anything that gives a platform to marginalized people and challenges social norms and power structures can be considered a threat.” — ”Art matters, but nobody wants to fund it.” by

.

Everything is not on the internet and lots of things on the internet are not true. Everyone knows this. Kids know this.

“Basically, the only thing it responds to are on the internet,” my nine-year-old recently said, explaining why he doesn’t think AI is the be all.

“Is everything on the internet?” I asked him next.

“No,” he said.

“What’s not on the internet?” I followed up.

“Important things,” he said with certainty.

An avalanche of nonsense

Literacy, critical thinking, number sense—foundational skills have always been more important than advanced ones. The problem is that AI tools convince people they can skip over the basics and go straight to advanced. And that seems especially bad given that the basics are often what AI tools are the worst at. Two copilots and no captain with common sense sounds like a disaster.

It was important to me to develop a foundational understanding of writing and research so I could enter the AI realm more clear-eyed, selectively taking what’s useful and leaving the rest. Skepticism is warranted.

Since I’ve spent more time searching online, I feel even more aware by how much can’t be found online and how much that is there just isn’t true. And because of that, I’m more cautious about AI-generated content of any kind, especially when it comes to information used to make important decisions or about sensitive topics and needs to be trusted.

Anyone should be skeptical about a summary amassed from a compilation of top search results found from a limited number of typical Google queries neatly arranged into what sounds like a college freshman writing to pass a class rather than to learn or think with nuance and depth.

AI tools assume everything’s online so of course they hallucinate, filling in gaps with whatever facts they find that best fill the hole from their limited data sets.

I’m dreading the avalanche of AI-generated content that’s already started to flow. It reminds of the shift from paper medical records to electronic ones. The advantages of digital were obvious and plenty. I especially didn’t miss the days of having to page a pissed-off prescriber to clarify their handwritten prescription that was illegible.

However, soon, copy-and-paste and dot-phrase shortcuts led to medical charts filled with redundancies and CYA legal wording, making the most clinically relevant info hidden within. Also concerning was that an error in one place easily got pulled into others. When you wrote by hand, you had to be precise and to the point. Things have improved since then, but the transition was messy.

More information does not mean more knowledge or efficiency. Often it’s quite the opposite.

As more quality content developed by experienced editorial teams is pushed out by the cheap and easy stuff, I’m dreading the decline in quality that’s likely to follow as content collapses in an AI-generated cesspool. Of course, no one knows for sure what will happen.

GenAI tools are like Cookie Monster—disruptive, messy, and unpredictable. For people and industries in their path, they’re downright destructive. (About a third of U.S. adult workers are worried about AI impacting their job opportunities.)

But GenAI isn’t the real monster threatening to eat us all. Artificial general intelligence (AGI) is, or the even scarier ASI—artificial superintelligence. However, in a Marvel-style plot twist, some believe the AGI monster will end up being the superhero, swooping in to tackle humanity’s biggest challenges.

Fear of what might be is hard to ignore when the stakes are stark and the situation so otherworldly surreal. AGI is both scary and fascinating, which means hype is inevitable. But how much is hype? Do you think AGI is imminent? Do we even know for sure that it’s possible? And what measure is used to determine when AI has definitively reached human-level intelligence?

Growing up with AI

I’m about equal parts hopeful about the potential that AI can offer, as I am concerned and skeptical. According to a 2025 report by the Pew Research Center, about a third of Americans fall into this camp. Another third predict a net negative, while AI experts have a majority positive outlook.

Whatever discussions you may be having (or not having) at home, kids are hearing about AI fears everywhere. There’s too much negativity and hype, especially for young kids who are just learning about the world and only starting to think about their future place in it.

My younger two don’t remember much before COVID. During the pandemic, our family didn’t experience the loss of a loved one or even a job. (Five years later, the hardships suffered and lives lost still haven’t been fully acknowledged.) My kids would say virtual school is the worst part of the pandemic they remember. That alone may explain why they’re skeptical that AI tech will make life better.

“What will life be like in the future with AI?” I asked my nine-year-old.

“It’ll be like the Great Depression, but maybe worse or a little better,” he solemnly said.

How could young people not be AI-weary when they’re told AI will be able to do anything better than them even before they even know what they want to do? Plus, there’s an inherent unfairness factor to AI that kids are very attuned to. Why even try if it feels like everyone’s cheating? And what’s the point if any skill you might be able learn and get good at will be outsourced to AI no matter how hard you try?

Some kids are ChatCPT-ing their way through school. Others are turning to conversational AI for advice and companionship (concerning x100). But some kids are also avoiding AI like the plague. Does that digital divide lead to a culturally significant one? And do parents or teachers even know what their kids are doing?

As AI freak-out pushes kids away from certain careers and fields of study that seem destined to be replaced by AI, what if AGI doesn’t develop as many expect, and AI alone can’t do the job? How will shortages in those areas impact everyone?

Trying to funnel kids into areas of study based on projected job outlooks always seemed flawed. And if you have kids like mine, you know, not all kids are funnel-able. I’ve tried. I’ve also learned that kids these days are resilient, creative, and willing to work without needing the work to define them. That’s actually a decent outlook to have and one older people like me can learn too.

Talking to kids about AI is super important—the ethics, the promises, and concerns. I’m still trying to figure out how best to guide my younger ones. But I’m reminding myself to be careful with the tone. Panics and doomsday predictions are only harmful. Kids should not be burdened by that. Grown-ups need to act grown up and lead.

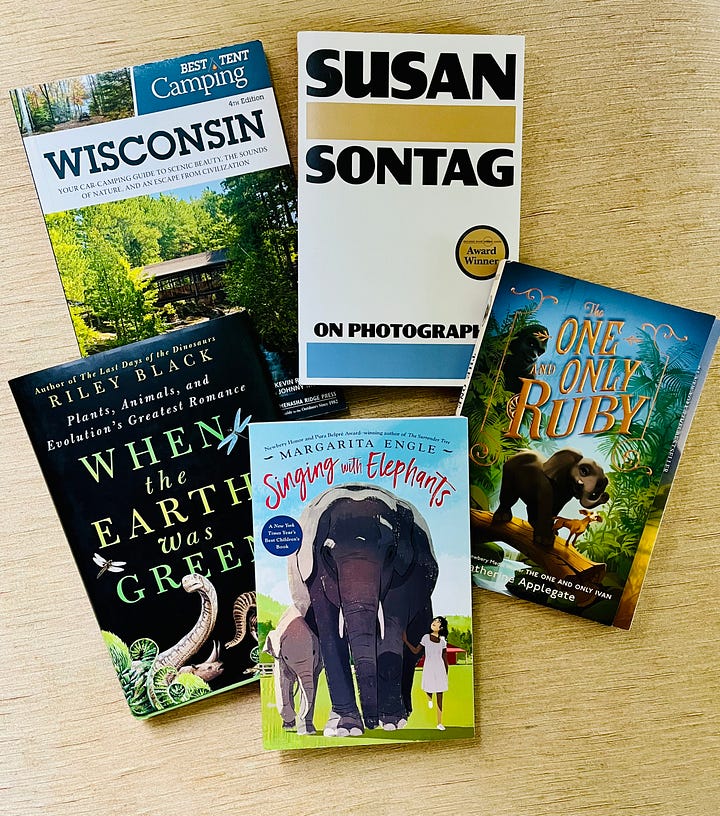

Our summer plans: Find hills to climb, ice cream to savor, and, lots and lots of books. If you’re ever in Spring Green, WI, check out Arcadia Books and The Frozen Local—the ice cream is heavenly! For the store-bought kind, my kids are good with the cheap stuff, Van Leeuwen’s is my new fave. And if I pick a flavor that says Earl Grey Tea, they won’t touch it.

Coming up: Next week I’ll post “AI-Powered Writing: 15 Practical Tips” (that focus on maintaining integrity and voice). Then, my fashion stylist daughter, Nora-Kathleen, recently went shopping for makeup and clothing with me to give me advice, which I’m looking forward to sharing here. Other posts I’m working on include “From tiny shapes to whole new worlds” and “Feeling Invisible? Here's Why It's Okay (and Sometimes Necessary).”

Links to more on AI

Empire of AI by Karen Hao is a book just out that seems to be on everyone’s TBR list—added it to mine.

Americans largely foresee AI having negative effects on news, journalists by Michael Lipka: According to Pew Research Center polling, “virtually identical shares in both parties say they are extremely or very concerned about people getting inaccurate information from AI (67% of Republicans and 68% of Democrats).”

What A.I. Offers Our Kids, and What It Takes Away by

: thoughts and links to AI’s impacts on kids.Explained: Generative AI’s environmental impact by Adam Zewe: “Rapid development and deployment of powerful generative AI models comes with environmental consequences, including increased electricity demand and water consumption.”

Why OpenAI’s Corporate Structure Matters to AI Development by Kevin Frazier: “The OpenAI saga underscores a critical vulnerability: Our governance frameworks are dangerously outpaced by AI’s relentless advance. Moving beyond patchwork state oversight to a federal charter system for labs developing AGI is no longer a theoretical ideal, but an urgent necessity.”

Copyright alone cannot protect the future of creative work (commentary by Brookings): “If current expectations of transformative AI prove accurate, however, the challenges to the future of work and the place of human creativity in a radically altered workplace will be genuinely hard to manage.” But they also say, “Of course, all of this might be just overblown AI hype.”

Millennials are leading the charge on AI skills development by Nicole Kobie: “A study from Workday found the cohort had the strongest belief in AI and was taking a more proactive approach to capitalize on the technology through skills development — though millennials and Gen X staff both largely agreed on the matter.”

Why Perplexity’s Cynical Theft Represents Everything That Could Go Wrong With AI by Randall Lane: “Perplexity generated more readers from the one Schmidt story it plagiarized from Forbes than it sent to Forbes from any and every post for the entire month of May. In AI nowadays, that trade gets you a billion-dollar valuation.”

Google and YouTube now control 25% of the world’s web traffic — but ChatGPT is quickly moving up.

Machines of Loving Grace by Dario Amodei: “It’s therefore up to us as individual actors to tilt things in the right direction: if we want AI to favor democracy and individual rights, we are going to have to fight for that outcome.“

From the Early Internet to AI Everywhere

It’s fascinating how many young people are drawn to the pre-internet era—or at least the idea of it. Although I remember lots of young 1960s obsessions in the nineties, so I guess it tracks. The sixties seemed so vibrant in contrast to the beige, bland, and corporate-ized aesthetics I saw every day. But not all boring is bad.

This is a well researched piece, Daphne, thank you. I've been sitting on my own newsletter about AI and all my conflicting feelings about it. The writing's on the wall of where we're headed and there's no stopping it. The world is going to change so much in the next few years.

I appreciate this thorough inquiry. And agree with you, we need to be equally curious and cautious. And want to believe that humans can and will find a way to utilize this powerful tool to benefit society, humans, the earth… maybe this it s naive?