Late '90s look behind the Walgreens counter on Chicago's North Shore

Walgreens was emblematic of major problems in the larger work culture and a professional ethos of staying compliant, agreeable, and always businesslike.

This story is Part Two of “My late '90s choice: Have a baby now or wait? Whose body is it anyway?” After backing out of a fellowship at the last minute, I needed to find a job fast after graduating pharmacy school January 1999. So I called Walgreens, knowing they hired quickly.

When I joined Walgreens in 1999, they were rapidly shifting strip mall stores to newly built drive-thru ones later called “at the corner of happy and healthy.” The number of stores were growing as prescription volumes were increasing at the start of two important changes: boomers were hitting middle age and the FDA just began allowing prescription medications to be advertised on TV.

On the one hand, Walgreens was frontline in terms of change when it came to technology, consumer demand, and anything related to their bottom line. My mom became a loyal Walgreens customer more than a decade earlier when Walgreens first shifted to having 24-hour locations. After ten o’clock was usually the first moment in the day when she remembered she had needs of her own.

On the other hand, Walgreens’ “trusted since 1901” culture seemed stuck in the 20th century.

The Weirdness of Walgreens

When I called Walgreens for a job, I must’ve set aside my maddening memories of working there as a cashier in high school . The smell of sugary, perfumey disinfectant always gave me a headache. The repetitive background noise of overplayed and outdated pop music or a replayed out-now-on-VHS movie was bad enough without the grating in-store announcement interruptions. I’d reached my sensory limit hours before the end of an 8-hour shift.

But the weirdness of Walgreens was not only the sensory annoyances—it was their culture. Walgreens’ old-school, traditional hierarchy didn’t evolve along with its other changes. One that was still too common then, but was starting to seem outdated.

A 50-something grandma working as a cashier was required to show deference to Mr. Assistant Manager half her age. But in the top-down culture, respect only went one way. And it's that same resistance to cultural change coupled with a bottom-line focus that has them still selling tobacco products under the same roof as blood pressure medication and kiddie toys.

During pharmacy school, I’d heard about the drawbacks of working in retail. “But how hard can it really be?” I wondered. In truth, I’d never been behind a retail chain pharmacy counter before. My community rotation was at an independent pharmacy. And when I worked as a Walmart pharmacy technician, all I got to do was shelve OTC products. Still, I was excited about starting a career as a Walgreens pharmacist.

I felt so honored for the opportunity and never wanted to forget how lucky I was to work as a pharmacist—instead of in a raincoat factory or tobacco field like my grandma Odessa. Or, like my mom, as a third-shift key-punch operator caring for little kids during the day.

And I knew community pharmacists were vitally important for protecting the public from medication harm while supporting proper uses. Plus, I knew they filled more needs than prescriptions.

Chicago’s North Shore

I started as an intern at a Walgreens smackdab in the middle of Chicago’s North Shore, just a few miles from Walgreens headquarters.

If you’re unfamiliar with Chicago suburbs, the North Shore is known as the premier place to live—and is likewise despised for this. It wasn’t that outsiders were jealous of the “rich people” who lived there—no, they resented the exclusive access to resources and security that came with those addresses. And the feeling of being looked down on by those who lived there.

The North Shore was in a league of its own at the top of the map and the top of the hierarchy. In a location, location, location real estate market, a North Shore address could easily triple the value of a home.

Perfection, precision, and protection permeated every nook and cranny. Even a public garbage can symbolized aesthetics and strength with its ornate forged steel design. No detail was too small. No size too big. And no other place could outcompete their schools, success and house-lust real estate.

Even with the privilege of blending in, I felt an uneasiness being there. Like I didn’t belong and maybe didn’t even want to. Like I was betraying the “What you think your shit don’t stink?” side of my family roots.

I grew up in primarily working-class Des Plaines. Families I knew seemed happy to be there. My mom has been a loyal resident for more than fifty years. Still, everyone understood its place in the Chicago suburban hierarchy. Des Plaines was below neighboring Park Ridge and Mount Prospect, where more professional-class families lived. But the hierarchical map’s weirdly shaped boundaries—which I’ve since learned were classist and racist by design—weren’t based on zip code alone.

Up until sixth grade I lived in an unincorporated, highly diverse townhome subdivision. And then we moved to a mostly Catholic, entirely white neighborhood with split-levels and ranches. Both were developed in the early ‘60s. Both were in Des Plaines. This is when I started noticing how much address mattered. It changed who you went to school with, which meant it changed who you grew up with. And years later as an adult, can affect where you feel like you belong.

Harder than I expected

I trained alongside two pharmacist men in their 50s. The gregarious one was the manager. The hilarious, mumbling-under-his-breath one was the staff pharmacist. “There’s a bunch a shit that you have to deal with, and it sucks, but life does too,” was their advice for me on how to adapt to the environment.

I’d worked in restaurants, doctor’s offices, and retail clothing stores. But hands down, this was the hardest job I’d ever had—then and now.

People on your left, on your right, and behind you watching you from their cars. The phone’s ringing. Voicemails and piles of scripts are growing. Everyone’s waiting. No one’s happy. And you’re trying to focus on checking one of the hundreds of prescriptions you’ll be signing off on that day, knowing no mistake is okay, and some could even harm someone. Oh wait, I forgot to mention the plethora of insurance problems that I don’t think anyone fully understands—and definitely no one wants to.

The physical demands of working in retail pharmacy are hugely problematic too. The first month working at Walgreens I nearly fainted. I couldn’t even speak. No words would come out. I thought I was having a stroke. A co-worker drove me to the ER. Still being an intern, I could leave without deciding to close the pharmacy down.

After a liter of saline, I felt much better. I was so dehydrated and didn’t even realize it. Having no breaks while working in a constant fight-or-flight state isn’t safe for anyone. Plus, being on your feet all day is even harder when you’re only standing in one place. I postponed trying to get pregnant because I feared being pregnant while working there.

As soon as my pharmacist license went through, I joined the floating pool of pharmacists in the North Shore region.

As a tradition, new pharmacists were “broken in,” scheduled every weekend and mostly late shifts. You got sent to the least-staffed stores on the least-staffed days. You got your schedule last minute so you couldn’t make any plans.

Lots of professions work this way. In part, the purpose seems to be to make the employees who get through it never complain out of fear of being sent back. And as a retail pharmacist, working alongside grossly underpaid pharmacy technicians doing similar work under similar conditions, complaining about your own situation seemed especially wrong.

No matter the volume, wealth is always heard. Whether it’s whispered or whether it’s in the form of someone threatening to tell Mr. Walgreens on you.

Fear of Mr. Walgreens

Wealth is intimidating, especially old money which has a culture of its own. Back then, some monied people wore fur coats and loads of jewelry just to pick up a prescription—a sharp contrast with today’s norm of signaling wealth quietly.

But no matter the volume, wealth is always heard. Whether it’s whispered or in the form of someone demanding you fill their prescription first or bend the rules towards them as they threaten to tell Mr. Walgreens on you after church. I watched the seasoned pharmacy staff manage to appease them while staying within legal boundaries of pharmacy practice.

The bigger fear came from Mr. Walgreens himself, though I think there were multiple of them. Fear started days in advance of a rumored visit. While floating, I worked a shift the day before “the visit,” and the pharmacist kept calling me with things to do, wanting me to stay hours after my shift ended to make sure everything was faced perfectly. Why was she that worried? It seemed the least important thing to worry about while juggling clearly more pressing matters.

Keeping up appearances always came first. Perfectly facing products covered up messes. Fake smiles and greetings glossed over genuine feelings. And “unbiased” metrics were used to justify biases. But adapting to the culture was part of the deal when you accepted a professional position and paycheck. Speak up, sure—only if it’s aligned with corporate culture and goals.

Then, one day, Mr. Walgreens came to visit while I was working. I couldn’t bring myself to say anything or even make eye contact with him as I stood in my station checking prescriptions—inside the two-by-two square box duct-taped to the floor. Always staying inside the box.

I got pregnant after leaving retail pharmacy for a home infusion position. We picked a name out in a baby-names book at Borders. Nora means light, and she has been a light in our lives. Nora started her first after-college job last month. Life is feeling very full circle.

Moving on

After several clinical pharmacy interviews I found someone who hired me with only a bachelor’s, no clinical experience, and no residency—something that’d never happen today. The onus today is on the employee to fund their own on-the-job training.

But before I left Walgreens, I called the district manager, another man in his 50s. I spent a day filling up a spiral notebook with complaints. Things like not having access to a clean bathroom while not being able to leave the pharmacy to use the better public one. Or how the “customer is always right” is so wrong. And the general dehumanizing treatment of their employees. “We’re treated like bodies, not people.”

He listened without interrupting. Nothing I said was news to him. He’d heard it all before, and I’m sure countless times again. The call ended with “Sorry it didn’t work out” and an inferred “Don’t ask to come back.” An unsatisfying end, but expected.

I’ve spent most of my career working as an infusion pharmacist. Lots of people think that it’s harder to verify IV therapies because of potential risks. But any medication can be risky if it’s prescribed or dispensed improperly. And the volume I check is so much smaller.

In retail pharmacy, checking lots of orders quickly is especially draining. It’s hard to make your brain focus repetitively in a fast-paced setting, ensuring that you’re seeing what’s in front of you rather than what you just saw. Plus, you’re working with loads of watchful eyes on you. And unlike the pharmacists today, I wasn’t having to fit in vaccinations while worrying about an angry individual shit-posting something about me or looking up where I live.

The fear of losing out leads to selling out. And I know at times I’ve sold out too. But I’m becoming less interested in buying into increasingly more things.

Regretful tradeoffs

Looking back, the weirdness of Walgreens was emblematic of major problems in the larger work culture. The professional ethos of staying compliant, agreeable, and always businesslike enabled corporations to ignore crappy working conditions and employee mistreatment. You were supposed to exemplify some superhuman form of excellence, getting the job done—fully and on time—no matter what.

Even before social media, people did speak up. But no matter how many people complained, nothing was done, ever. Because it seemed like once people became decision-makers, they got quieter. They tended to look the other way and avoid anything that might rock the boat. Which might seem odd. Shouldn’t someone in a more secure position be willing to take more risks for the right reasons?

Maybe they got too comfortable: nice-to-haves became must-haves. Or maybe they didn’t wanna risk losing out on stock options and now non-existent pensions that were akin to winning a lottery. Leaving money on the table is always hard to do and often leads to people making tradeoffs they’d later regret.

The pressure to always say “I’m fine, I can handle this” wasn’t helpful for anyone. Self-compassion isn’t selfish. It actually makes you more able to empathize and give.

I wonder about the older pharmacists that were my dad’s age. Did they push through to the end and have a happy retirement? Or were they like my dad who died of a heart attack shortly after reaching the finish line? I saw the effects that working 60-work weeks under constant stress had on his body, especially after 50. But no matter what, he showed up, never complained, and got the job done.

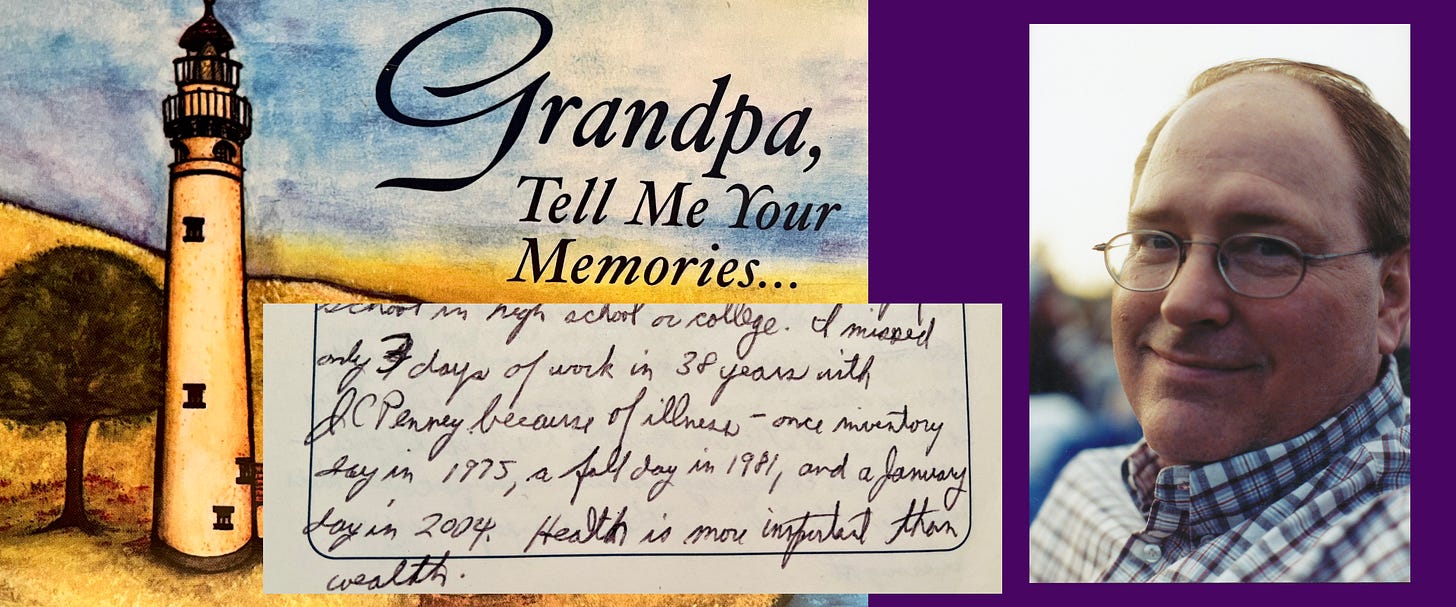

In 38 years working in retail at JCPenney, my dad used two and half sick days—”one inventory day in 1975, a half a day in 1981 and a January day in 2004,” he wrote in a Grandpa, Tell Me Your Memories book just before he died, adding in “Health is more important than wealth.” When asked to describe himself on another page, he writes “RETIRED AFTER JOB BURNOUT.”

One of my last phone conversations with him was about his recent physical showing his numbers going in all the wrong directions. In between making PB&J school lunches and folding laundry, I think I told him to do something silly like “eat salmon and blueberries” and “try out spinning”—it was 2008. His body would be something he’d take care of later, he told me, after he retired and had more time.

I know my dad would’ve walked away from that job had he known the tradeoffs to his health and lost time spent with his precious grandkids, most of whom he’d never meet. Maybe he still would’ve died at 60, but at least would’ve spent his last years doing what he wanted. And maybe he would’ve set an example, showing that it’s okay to let go.

Striving and stretching

In 2006, my husband and I made the stretching and striving move into the North Shore with our two young kids. If you can afford the best schools for your kids, why shouldn’t you give it to them?—a question that no longer feels rhetorical.

Seeing the North Shore from the inside, I learned, of course, they’re just people. There’s no such thing as a monolithic group, period. There’s no singular story. Lots of individuals with lots of complicated reasons that only they know, but like everyone else, are probably too busy to understand at the moment. And like everywhere else, people are generally nice and nice to be around.

After my dad died though, my husband and I started rethinking the tradeoffs of grind culture and the performance pressures our kids faced being in a top-1% school. We moved away just before our oldest went the seemingly sacrilegious route of going to community college after high school.

Final thoughts

Approaching 50, looking back half a lifetime ago, I have a mix of so many feelings. I regret selling out for things I definitely didn’t need and sometimes didn’t even want. I’m growing less concerned about fitting in. And I’m becoming less interested in nice-to-haves.

I’m also too old and tired to ignore my instincts. It doesn’t mean I’ll always follow them. But I’ll at least listen over the stream of sometimes rational and other times creative ways to justify something you’re told to think is true (or at least pretend is true) though your gut says it isn’t true.

The most frustratingly shocking thing is how long it takes from the time a serious problem is identified to the time it gets addressed in any meaningful way. But that can’t be an excuse to accept the status quo “as is.” Yes, the older pharmacists were right: There’s a lot of shit to deal with in life, and it sucks. But lots of sucky parts in life can become better and fairer. That I know.

Dr. Bled Tanoe Says Fix the Pharmacy, Forget the Pizza

“Yes, I love pizza, but it is no longer cutting it,” pharmacist Dr. Bled Tanoe wrote three years ago in an open letter to retail pharmacy upper management. “You can’t expect people to survive this amount of work with no help. We are drowning.”