My parents' cost-of-living struggle in the '70s. Why is help still so hard to get?

Hearing my parents' voices in letters from 50 years ago has got me thinking about the impossible choices too many families face. Did the '70s really ever end?

Our home is filled with all sorts of anticipation. Yes, the holiday kind—our second-grader is antsier than usual, counting down the days to Christmas. Our seventh grader is more excited about a winter break from school and its junior high-ish annoyances. My husband’s looking forward to a few treks through Wisconsin’s winter woods. My own anticipation is somewhere between low-key dread and grateful contentment, depending on the moment.

Christmas has lost its sparkle, little by little in recent years. And now, poof, it’s gone. Is that just part of growing older? Like after some threshold of repetition, boredom becomes inevitable. Or maybe Christmas seems duller as the veil of estrogen is lifting off in my late 40s. A veil that once made the delusion of holiday magic possible when the hazy multi-colored lights glossed over my discerning side—at least on some days of the month-long season.

Our grown kids hold the most interesting anticipation right now. Our daughter is getting ready to start her first-ever full-time job. And our high school senior is waiting to hear back on his early-decision college apps. Seeing them in this life phase stirs up memories of my own experiences. But it’s also making me think even more about how young my parents were when they became parents at 19 and 21.

My oldest son is looking a lot like my dad did at his age, before my dad’s face and Bavarian belly filled out his profile. I see my dad’s jawline and smile below a pair of glasses not nearly as thick—thanks to my husband’s non-myopic half. He drives like my dad. Wears turtlenecks and a camel-colored suede coat like my dad. Listens to some of the same music. And like my dad, he’s applying to the University of Wisconsin (UW) Madison. But that’s where the similarities end, and their contrasting outlooks at the same age become interesting.

Catalog dreaming

My dad and his cousins were the first generation in their family to think about college. And the first to leave their Catholic rural enclave—almost entirely. As a kid, the seed was planted for my dad while sitting on the porch stoop talking to his grandpa who showed him the holes in his shoes. “Your life will be different,” he told my eight-year-old dad. “You can go to college and wear a suit to work.” His grandfather saw college as a path to both comfort and respect. And the hope of a better life for his grandkids gave meaning to his decades of back-breaking work.

For any kid growing up in a 1950s sparse, make-do home, department store catalogs sold anything you could ever wish for. My grandma told me many times, how for months after my dad’s Irish twin sister died, he kept asking her if they could buy another Karen from the catalog.

But as Dad got older and more peer-focused, the stuff in the catalog became measures of relative success. In my mom’s childhood home, catalogs served as outhouse toilet paper. But my dad grew up middle class enough to imagine having the stuff he saw on the dream-filled pages, and he was close enough to a few kids who actually got to get what they wanted.

The seductive allure of the stuff of the capitalistic late 20th century stirred my dad’s competitive drive for material success. College-bound and determined, he first had to convince his parents he could afford to go.

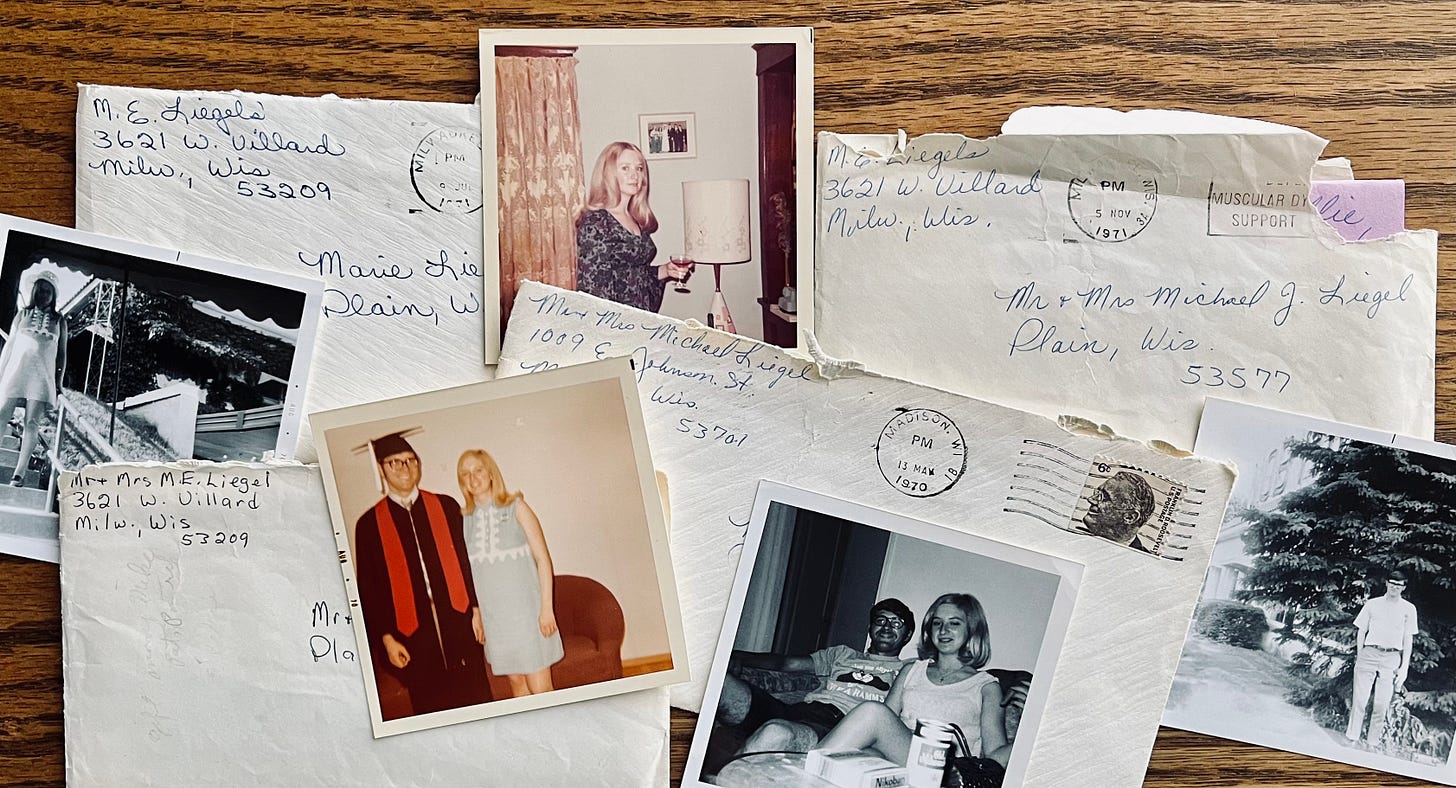

The Polaroid generation

My grandma saved Dad’s college planning number crunching note from 1966. Dad estimated a year’s expenses at a flagship state university, including clothing, toiletries, and spending money, to be about $1,500—or $13,000 in today’s dollars. He didn’t get the help from his parents he was hoping for—they were his expenses for him to meet—so he took out student loans. Still, at a fraction of today’s costs, it was doable.

Dad was a poli-sci/history major planning to go to law school. Midway through college he met my mom at a UW campus bar. Two years younger—but a decade or more ahead in life experiences—Mom worked as a key punch operator at a bank. She left the foster system at seventeen, supporting herself, which early on landed her in the hospital after going without food for a week. With her older brother in Vietnam and younger sister adopted, she was alone in the world, aside from some scattered extended family. And she learned to count on herself and herself alone.

My parents married in October of Dad’s final year of college. Still in the mod-60s, my parents came of age just before hippie culture took over. Their siblings, just a few years younger, seemed to be separated by a whole generation by the way they acted and dressed.

Mom had platinum blonde sculpted hair and wore brightly colored mini-dresses. Dad tried to look cool in his snug-fit polyester pants and patterned button-ups but couldn’t avoid a bit of a nerdy look with his thick, black, horn-rim glasses. They didn’t know what to expect as a married couple but knew they didn’t want to end up like Dad’s bickering Archie-and-Edith parents. They were the full-color TV generation and wanted that rich, vivid color in their own lives and relationships. Less formal but more real. And with an aesthetic sensibility worthy of a Polaroid.

Change of plans

On December 1st, six weeks after my parents married, the first in a series of dreaded draft lotteries was held. Dad died on December 1st. But on that same day in 1969, he lucked out. His birthdate was number 257. Dad understood those odds—virtually no chance he’d be called up for military service. But he was totally clueless about the chances of pregnancy, seemingly shocked when Mom soon found out she was expecting.

Neither of them had any real idea of how fertility worked. Birth control was available but not easily accessible—nor acceptable in Catholic circles. On top of that, options were limited. And no one they knew talked about such things.

With the baby coming, Dad needed to forgo plans for law school. He found work as a service attendant at a Phillips ‘66 Motor Oasis service attendant third shift—first part-time and then full-time after graduation. The pay was $2.35 an hour—“It sure isn’t the greatest job, but it’s a job,” Mom wrote to her mother-in-law. “I’m sure something better will turn up.”

My grandma saved letters my parents wrote to her during this time period. It was fascinating to hear my parents' voices at my kids’ ages. It was also fascinating to see the beginnings of who my parents grew to be. At nineteen, about to have her first baby, I could hear the future recruiter in Mom’s voice—a role she’d end up spending thirty years in.

Mom found Dad’s first JCPenney’s job in a newspaper ad—a place he’d end up at for nearly forty years. The deal then was that a staffing agency would connect you to the employer, and then you’d owe them a month’s salary. And if you didn’t pay, they knew where to find you.

My parents’ first hurdle was moving to Milwaukee where the job was located, which in 1970 was more expensive than Madison. They moved a few weeks before Mom gave birth to Patrick, and quickly realized Dad’s income wouldn’t be enough to get by. But like always, Mom found a way to make it work.

Throughout my parents’ marriage, Dad was the one who freaked out and Mom was the one who figured out. She could find a solution for anything. Growing up, I really believed she had magic. “Watch, I’ll make it disappear,” she’d tell me when she put lotion on me after a bath. She was like Samantha from Bewitched. Fixing and cleaning everything. Making everything perfect once again. And then letting my first-Darren type dad get the credit.

Funeral home arrangement

With their newborn Patrick, the family of three moved into an apartment on the top floor of a funeral home. In exchange for rent, they’d both help out whenever needed. Mom would leave Patrick in his crib while he napped or played. Run down two floors to set up for visitations or three floors to do laundry in the basement where they embalmed the bodies. Dad went on ambulance runs and helped carry the bodies.

“After work I have to help get a body from the airport,” Dad wrote to his parents. “Tomorrow I help get the body in a casket and get the chapel prepared and sit downstairs while the body is in state.”

Dad resented his personal ambitions being thwarted. And he was unprepared for life outside of the structured order of his insular upbringing and then college dorming with cousins. His fears led to constant worry—worry about not having enough or someone having more. And worry that someone might see the scared young man underneath his cheap polyester suit.

Early in my parents’ marriage, a priest once told them “You’re on completely different wavelengths.” And I could hear that contrast in their voices while reading their letters. Mom was thrilled to be a mom and have Patrick to love and care for. After having so many losses and separations in her young life, motherhood was a gift. And after having lived through so many close calls, few things scared her.

With the economy down and everything, if this Christmas isn’t successful, I may find myself out of a job.

Breadwinner stress

While Dad was consumed by fear, Mom was completely ignored, sometimes not even spoken to. She solely cared for Patrick while trying to become the future homemaker of America that she trained to be in high school—on a penny-pinching budget.

A few weeks before Christmas 1970, Dad wrote to his parents asking them for help. With a family to support, he was worried. “I would like so much for you to come to Milwaukee and buy stuff from my department. Sales are down and I need a sales increase badly,” he wrote. Knowing Dad, I know he must’ve felt pretty desperate to write those words. He continued, “With the economy down and everything, if this Xmas isn’t successful I may find myself out of a job.”

Dad pitched an idea. He’d meet them in Madison when they went to visit his younger brothers in high school seminary. “You could look in the catalog and pick out the stuff which you would like. I could buy it with my 15% discount card so that the inconvenience of doing it this way would be compensated,” he messily wrote, then promised he’d try to write neater. “Remember I’m talking about housewares, gifts & lamps only, the department I work in,” he reminded them.

The next two pages are filled with gift ideas, referencing their page numbers. “Dad, I do carry small appliances, TV trays, wall decorations—many Ma may like for Xmas. We have a stainless steel fondue set for fifteen. And we have early Roman pictures, one for $11 or two for $22.” (Did that sales tactic work then?) Dad listed what they bought so far for Patrick—a crib for $11 and an out-of-season returned motorized swing for only $4.50. But then mentioned they really needed clothes for him.

“Hope you don’t take this letter wrong. I would like you to do business in my department because I need sales ever so badly and we do have good merchandise,” he closed, just before mentioning “Pat’s brother is home from Vietnam so we are going to visit him. This will be good because he can tell us the cheapest way to winterize our car. And I can probably have the side window put in from the junk Pontiac setting outside.”—like that’s the first thing you should ask from someone who just came home from war.

But Dad was raised to put the practicalities of having your ducks in order above all else, especially niceties. Always all business was easy for Dad because he was also always clueless about how someone else might feel.

And then came Mom. She smoothed out Dad’s sharp edges, kept him from putting his foot in his mouth, and saved his ass countless times. Mom felt needed, with a sense of purpose and loyalty for family. And she loved the sensory aspects of bringing comfort and care.

But Mom had no frame of reference for Dad’s crassness and coldness. And the only thing that made sense was for her to take it personally. I know I would’ve ended up feeling that exact same way at that age (or maybe any age) no matter how many self-help books I read and Oprah shows I watched.

If we can just make it through the winter, perhaps even trying harder to please them, we’ll be sitting pretty good.

Sitting pretty good, hopefully

I don’t know if my grandparents ended up buying anything, but they did lend my parents $80 (about $500 in today’s dollars). And that eighty bucks became a frequent topic in letters.

“Snelling and Snelling phoned Mike at work and demanded their money by the first part of next month or they would take us to court,” Mom wrote the following spring, pregnant again. “So that means all our paychecks need to be devoted to that. We want to get you all payed too. By October we plan to have you all completely reimbursed. In fact, by then our slate should be clean, except for car payments, school loans and dental bills.”

Meanwhile, their funeral home living arrangement grew more tenuous as they struggled to pay bills. Moving out wasn’t an option. “We won't be able to meet you in Madison this weekend,” Mom wrote in July, explaining that they needed to stay at the funeral home more often, especially on weekends. “If we can just make it through the winter, perhaps even trying harder to please them, we’ll be sitting pretty good.”

It’s not always easy to see your parents as people. Which is weird because you see them during their most human moments. When they’re on a good-news high or so happy they cry. When they’re beaten down, heartbroken, or depleted. When they do the things they swore they’d never do. Or find the strength to get through something they never thought was possible.

Every new memory of parents is superimposed on the last, starting from the earliest ones when you looked up at them from a few feet below. Their expressions and voices become permanently hardwired in your brain, and you remember how they reacted to your behaviors as you tried out different versions of yourself.

They’re your first audience and often your greatest fans. They want your picture, save your firsts, and tell strangers about you. It might not always be true, but I’ve found it’s more true than most people ever know.

Rust-belt Rockford

A month before Christmas 1971 Dad was transferred to Rockford—a small, rust-belt city 90 miles northwest of Chicago. The good news was housing was more affordable. They rented a bungalow on Oakley Avenue, walking distance from Penney’s. Free from the funeral home but their money troubles followed. “We have so many debts, including the $80 we still owe you,” Mom wrote, now very pregnant.

“We’ve been trying to get at that but it seems there just isn’t anything left of our checks. If you want it now tell us and we’ll put someone off another month. I am aware how unfair that is to you so if you want it before then because it will have to come out sometime before Xmas. In January, we have to save all our unclaimed money for the baby’s hospital bill.”

Borrowing money from family is almost always awkward. More so for some than others. Some families with little help a lot; some families with a lot help little. And sometimes you can’t see the price in emotional drama until it’s already paid.

My parents didn’t end up “sitting pretty good” in 1972. Teddy was born in January with spina bifida, a congenital condition the doctors in Rockford considered untreatable. The hospital literally put Teddy in the linen closet instead of the nursery.

Mom had to fight to see Teddy, and fight to keep him alive, which meant she had to leave Teddy at Children’s Memorial hospital in Chicago and only visit on weekends. The Ronald McDonald House that helps families stay close to their children during hospital treatments was still a few years away from opening.

Impossible “choices”

Letters to my grandma became sporadic after that. Dad was transferred to Chicago the following year. Shopping malls were booming in suburbia and every mall had a Penneys. Malls were my generation's version of a catalog—a place where anything is possible for a price.

My parents rented a two-bedroom townhome, but with rent costs double that of Rockford, they couldn’t make ends meet without Mom working. With no childcare or family to help, Mom picked up third-shift data entry work on and off while caring for Patrick and Teddy during the day, which meant she spent the 70s getting a half-night’s sleep at best. And she worked like this through pregnancies with me and my younger brother.

When Mom’s body started revolting in mysterious aches and pains, Valium became the medically endorsed solution to tolerate the intolerable. And she wasn’t alone. Valium was the top-selling prescription drug throughout the 70s, with 2.3 billion tablets sold during its peak in 1978.

As the distance between my parents changed into sky-high conflict, Valium became symbolic for the price Mom paid for tolerating the intolerable. When Mom divorced Dad in 1984, she placed her wedding ring in her last prescription vial, ending a chapter. Though it never had the feel-good closure and certainty stories are supposed to have.

As I see the next generation come into adulthood, I see my parents’ struggling start as a tiny piece in a story much bigger than their own, or even my family’s.

I see struggles that never needed to be quite so hard. Support that could’ve been available. Understanding that should’ve been had. And awareness of how much harder it would’ve been for them (and me) if they didn’t have the privilege of blending, moving from town to town, only worrying if they could afford the rent—not if they’d be welcomed or safe. They may have struggled to pay for essentials, but they had a dentist who would fix their teeth without a full payment upfront and in-laws who had something to lend them in an emergency.

Families need more support—without shame or strings attached.

Does everything need to be wrapped in a story?

Gift wrap has become another holiday dilemma. Wrap and waste? Or spare landfills and the magic? An unwrapped gift doesn’t feel the same. It just doesn’t. The sight alone of a wrapped present fuels curiosity and anticipation. And the multi-step process of opening it—even though lasting mere seconds—feels satisfying, just like finishing a good story.

Christmas wish

This is one of my favorite Christmas pictures from childhood. Through the plastic film covering the bay window everything inside is blurred just enough to feel both real and magical. Dad must’ve stepped outside with his 35mm loaded with slide film. Each Kodak Ektachrome image was another catalog item in his wish book. Each proof of something had. Each leading to something else wanted.

I see Mom inside and can imagine her face as I remember—tired and surrendered, but with just enough left to keep going while trying to make things better. They were both so young, unprepared and unsupported. The biggest Christmas wish I ever had was for my parents to have it easier.

Seeing through the blurred image, I feel more clear-eyed that struggling starts can be made better. Families need more support—without shame or strings attached. Putting it all on parents is unfair. And while extended family is important, not everyone has family with the means or willingness to help. And sometimes the help costs even more in dysfunctional family stress, guilt, and conflict.

Reproductive healthcare and education are important and life changing. My parents would have chosen to postpone parenthood if they had the option. Respect for choice is also important and it goes both ways. Coercing people to have children is abhorrent. So is blaming people for having children at the “wrong” time or without the “right” set of resources or life circumstances.

Dad lived the American Dream, clearly “better off” than his grandfather. But was he really?

Final thoughts

Dad came of age resenting his parents for not helping him more. Despite Dad having multiple times their means, he ended up helping his own kids even less, including Patrick who did everything for him and Teddy who clearly deserved extra help.

He died in 2008 owning two houses and two cars and having a six-figure pension and seven-figures in savings. He traveled the world, ate at some of the best restaurants, and attended some of the biggest sporting events. He lived the American Dream, clearly “better off” than his grandfather. But was he really?

Dad lost much of his family to conflict, causing a deep sense of loss that grew bigger as he grew older. He worked 60-hour work weeks until he retired, just sixty-some days before he suddenly died. He died more than a decade earlier than his grandfather. Was the stuff in the catalog worth it? Did having more material things end up meaning anything in the end?

Losing Dad when I was 34 made me rethink a lot about “stuff”—real stuff vs. material stuff. My favorite Christmas memory is from 2010, when my middle son was a newborn. From the outside, my life may have looked like a Pottery Barn catalog in our Northshore brick-and-cedar colonial. But something inside me was really feeling wrong. Like my identity was merging with stuff, the way Dad’s had. And likewise, my energies were becoming devoted to holding on to it all.

After losing a baby boy in the fourth month of pregnancy the previous year, little Owen felt even more miraculous and awaited. One tiny moment touched me and stayed with me ever since.

Our oldest son was so excited about his little brother. On the yellow-brick-road kitchen tile floor that looked warmer than it felt, Konrad sat by Owen's bouncy chair and sang his made-up song over and over, “I love you Owen more than stuff / I love you Owen more than stuff.”

People over stuff. It’s that simple. And that hard. But worth the struggle.

What’s next?

I’m over-the-moon excited to talk to former Walgreens pharmacist Bled Tanoe and share our discussion here. Bled is founder of #PizzaIsNotWorking, a nationwide movement to improve public safety and working conditions in large chain pharmacies. And she's the author of Surrendered Motherhood, a beautifully written memoir.

Related reading:

When Your Dad's a Jerk, Is it OK to Accept His Love?

Mourning my brother while missing the '70s—our first decade of life

Lately, my headspace has been stuck in the ‘70s, when my brothers and I were born, starting with my oldest brother Patrick in 1970. The same one who late last year became the first one to die. Just like that. No accident. Just from natural causes, including despair.

"My own anticipation is somewhere between low-key dread and grateful contentment, depending on the moment." Love this relatable summation of the complicated mix of feelings that come up during the on-ramp to the holidays!