After I lost my brother, I longed for childhood like never before

For the first time in my life, I’m mostly surrounded by people who have no memory of the 1970s. After my brother died, I wanted to go back to when we were kids.

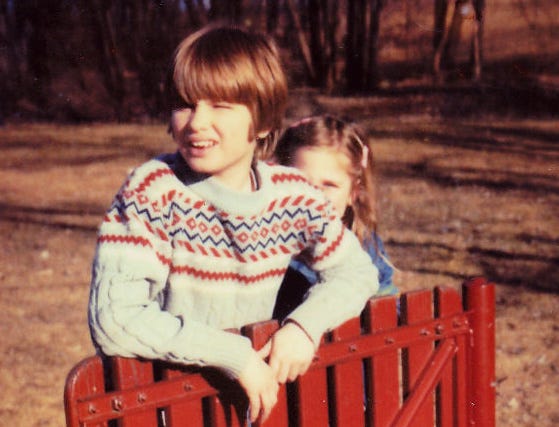

Lately, my headspace has been stuck in the ‘70s, when my brothers and I were born, starting with my oldest brother Patrick in 1970. The same one who late last year became the first one to die. Just like that. No accident. Just from natural causes, including despair.

Losing a sibling is gut-wrenching. It’s also a reminder of ongoing generational change. Natural, but somehow unexpected too.

For the first time in my life, I’m mostly surrounded by people who have no memory of the industrial-earthy ‘70s, gritty and smoke-filled, but warm and flowing with natural whimsy too. It’s slipping away, but I’m not ready to let go … not yet.

Life felt full of possibility in the ‘70s growing up in my family’s two-bedroom townhome northwest of Chicago. It will always be home in my heart.

The bold, earthy ‘70s

I only remember the big issues from the bold, earthy ‘70s for the significance they had in my own little-kid life.

Inflation meant wearing boy's hand-me-downs, sharing a bedroom with my three brothers, and eating Hungry Jack pancakes for supper (which was just fine with me).

Crime meant watching out for “stranger danger” and seeing scary local news teasers.

The faulty promises of fair housing meant living in a diverse neighborhood that was an anomaly due to its unincorporated status.

And the shifting gender roles meant an ongoing, adversarial undercurrent between my parents causing me to grow up fast amidst the drama.

The high conflict drama between our parents shaped much of our childhood. And the conflict was sky-high: plates flying, police coming, Dad’s warring words and Mom’s masked pain. And the came a long separation, a reconciliation and a few years later, a drawn out, lawyered up divorce that ended the marriage, but not the conflict.

But even with all the bad drama, life felt full of possibility in the ‘70s growing up in my Catholic family of six and living in our two-bedroom Colonial Ridge townhome northwest of Chicago. It will always be home in my heart.

Our Colonial Ridge 2-bedroom

Our Robin Drive townhome was the last place my family lived together. Dad died years ago. Now Patrick’s gone too, and I’m feeling homesick for that place I keep seeing in my dreams and memories.

The living room’s cathedral ceiling and the four levels of living made the inside feel bigger than its actual square footage. And homey too, with a color palette of textured, earthy décor. The avocado green carpet and orangey-brown parquet floors always felt warm.

Our oversized floor model TV — my first window to the world — sat next to a 4x5 grid bay window. Outside I saw a mirrored row of townhomes across the street and a tall beige hospital with grids of windows off to the not-so-distant east.

It wasn’t only the hospital where my younger brother and I were born. I used to think it was the General Hospital—the place filled with juicy, soap drama that I watched with Mom huddled around our second TV, the 9-inch Zenith, black-and-white one, furthest away from my napping little brother.

During the cold months, when our window view of the hospital was obscured by a 0.7 mm thick sheet of plastic, the frequent ambulance sirens kept reminding me of its presence in a weirdly calming way.

The worst part of living in our townhome was dealing with Raid-resistant water bugs. They’d come out at night in the kitchen and bathrooms and quickly scatter when you turned the light on. This was a real problem when I woke up in the middle of the night and had to pee. Should I wake up Dad? The few times I did, I learned not to do that again. I could call for mom, but she worked third shift as a key punch operator.

Eventually I found my own workaround. I quickly turned on the bathroom light. Then, I’d close my eyes and count to ten just outside the door. Usually, they’d be gone by then. But I kept my tennis shoes right by my bed to easily slip on just in case I still ended up stepping on one.

Outside of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, being a kid wasn’t special in the ‘70s.

Growing up free-range

Growing up free-range meant the space outside was just as much a part of my home. The tiny patch of backyard grass, or sometimes dirt, combined with all the other units into one big courtyard of space where there was always someone to play with and something to do.

We had a sandbox, several versions of flimsy metal-ish playsets, and a picnic table that we’d run to when our mom came out with a tall pile of sandwiches cut into fourths and a Tupperware pitcher of Kool-Aid.

Not to brag, but everyone on our block thought mom’s PB&J’s were the best. No matter how tired she was, she always spread the Skippy uniformly across the entire slice of Mother’s bread and never smooshed the other slice when she spread the Smucker’s out completely smooth.

Plus, we had our own natural features. An alley that flooded and turned into a swimming hole. A drainage ditch “crick” full of crayfish. It had a concrete platform just above it — the perfect place to hang out with a friend and talk. And nearby was a pond on hospital property. Through the chain link fence we could feed the ducks and geese during the warmer months.

Old world Wisconsin

My parents were both from rural Wisconsin. They grew up around farms and loads of cousins. Visiting was like driving back in time, to a world not that different from their 1950s childhoods.

On long weekends and during weeks in the summer we stayed with Dad’s parents. With the precision of a German clock, the tiny, Bavarian town had a rhythmic movement in accordance with the day, season, and Roman Catholic calendar. The noon siren brought the men back home to dinner tables filled with ring bologna, boiled potatoes, and sauerkraut.

I didn’t mind visiting for a day or two, but couldn’t wait to get back home. I missed the sounds of airplanes. With every takeoff and landing at nearby O’Hare airport, I imagined all the possibilities of people and places to go. I even missed the smell of pollution — it sure beat the farm fresh one permeating the whole rural Wisconsin region.

Best place in the world

This was home. I knew my few blocks of home must’ve been one of the best places in the world because so many families chose to make it their home too. People came to our unincorporated Des Plaines neighborhood, wedged between Niles and Park Ridge, from everywhere.

American small towns like my parents. Chicago and other large cities. Immigrant families from far and wide. And families from different economic backgrounds too. Families with doctor dads and families that couldn’t afford a phone line all lived on the same block.

We shared the same space. Played together. Ran around together, outside and in. Our home meant having a chance. Something bigger than the generation before. And something wider than ever before. I felt such a connection to everyone through a feeling of hope. And I saw that same hope through my window to the world watching channel 11 public TV.

I felt loved too. I always knew my parents loved me more than anything, just like other kids’ parents loved them. Mom gave the best hugs. Told the best stories. Made the best chicken and dumplings. And she always had some trick up her sleeve to fix any problem.

Dad had a zest for life and a touristy curiosity, always with a 35mm camera hung around his neck. He took my brothers and me all over town, put us up on his shoulders, and pushed us to do something we didn’t think we could do.

But outside of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, being a kid wasn’t special in the 70s. From an early age, I never felt like my existence alone deserved space. I knew I’d need to find it myself. But finding space meant belonging. And that meant fitting in. And that required a lot of figuring out.

We shared the same space, outside and in. Our home meant having a chance for something bigger and wider than ever before.

My first window to the world

So as an introverted kid I watched and listened to every conservation around me, especially the ones I wasn’t supposed to hear. And as a latchkey kid, I spent more time listening to the ones on our static-y, cube-shaped floor TV set than any real life ones.

Pretty soon I realized this: Aside from fantastical talent or incredible luck, a chance for something better would come from books. Those 26 letters that I was learning about on PBS, could take me wherever I wanted to go. And when things got really bad at home, that possibility meant everything.

Nursery school was the perfect place to start. While Mom was the first to go to high school and Dad the first to go to college, my brothers and I were the first to go to preschool. My world grew bigger. New same-sized friends. New rules to follow. New smells of salt dough, tempered paint, and vinyl blowup letter people.

And preschool brought new feelings about what it meant to be a girl, outside of my own family of boys.

Nice and pretty is harder than it looks

I started out feeling like I could do anything my brothers could do—that I’d want to do. (Hunting, fishing, and sports were not my things.) But as I entered school, I started realizing that it was gonna be a lot trickier for me.

A woman’s success was inexplicably connected to both being nice and looking pretty. But almost no one had the “right” kind of beauty; and absolutely no one kept it. What’s more, being considered “nice” wasn’t simple. And having too many thoughts of your own was risky.

Barbie through the hypnotic spiral of nostalgia

From My First Barbie to pukey pink to not wanting to be fatter than the guy: I never wanted to see Barbie again. And now Gen Z's got me rethinking.

I couldn’t figure all of that out. But as a kid, I knew I had some time before I really needed to worry. In the meantime, I worked on being nice by smiling and saying lots of Hail Marys.

I practiced being “pretty” through the magic of makeup. First when Mom made me up for dance recitals. Then when I painted my own face, sneaking some from her stash when no one was looking. Later, Santa granted my wish with a Fresh ‘n Fancy cosmetic kit so I could mix up my own magic. I knew the rest would take some time.

Until then, I ran around the house in my Wonder Woman Underoos, hoping that my body would magically morph into the same Barbie bod when I became a teenager.

While I was waiting for that to happen, my life kept changing in unwanted ways. After a yearlong heated divorce battle, Dad moved out. My brother Patrick had already moved away by then, escaping the drama to live with our grandparents. Many of my friends were moving away too.

Those blocks where everyone seemed to come for a chance for something better, started becoming a place that people moved away from if they could.

The other side of train tracks

During winter break of sixth grade, mom remarried and we left our Colonial Ridge townhome. We only moved a few miles away to the other side of Des Plaines. But it had a completely new culture. Entirely white, mostly Catholic two-parent families with many dads working in the trades. This split-level 60s neighborhood was going to be my gateway to more opportunities.

As a 100% commission headhunter, mom worked her butt off to give us opportunities she never had. She spent days working in a smoke-filled office, rented in a ten-story high bank building. She spent evenings working in the kitchen, doing dishes while talking to clients on the phone, with the coiled cord stretched stick-straight, barely able to reach the sink. And when I woke up in what seemed like the middle of the night, I’d usually find mom folding clothes, sorting through paperwork, or making school lunches.

Then, Mom did it all again the next day, getting dressed up in Chas A. Stevens suits, with shoulder pads and pencil skirts, and painting her face with Mary Kay. And for added discomfort: a pair of L’eggs control-top pantyhose and 3-inch pointed-toe pumps. Required business attire for an 80s working woman.

One and the same with your mom—why is separation so hard?

“Just be glad you have a pot to piss in and a window to throw it out,” I grew up hearing Mom say. And I get that. It’s absurdly silly to think I now live in a home with four flushable pots and countless windows opened only for the fresh air. I know how new that possibility is and how rare it is today.

How could I feel anything but grateful to be in that space that she sacrificed so much to provide? My mom grew up poor and later in foster homes. So I knew how lucky I was just to be there.

But secretly, I was feeling boxed in. Like being stuck in one of the grids on my old living room window, or my new one, now 5x5. My view of the world grew more cynical. And my home life became more complicated.

The hopelessness of my parents’ getting along shifted to a hopelessness that my stepfather Gene would stop drinking. No matter how hard they tried. No matter how hard he tried. Some things just can’t happen. Marriages end. People die, sometimes slowly.

The Mikes were simply replacing the Archies in the hierarchy. For the Glorias, the expectations multiplied.

Those were the days … that never ended

It was there in my 10x11 bedroom, wallpapered with three different floral patterns, when I began understanding the 70s a lot better. I became hooked on the beloved sitcom, All in the Family.

The TV show became like my second family, their familiar voices drowning out the background noise of my own family, which was usually a bunch of brothers with a bunch of friends making various loud, non-word sounds while crowded around the TV playing Nintendo. I eventually watched every episode in a piecemeal, random order.

I found the Mike and Gloria subplots more personally relevant. Mike was the first of his generation to go to college, just like my dad, also named Mike. Gloria and my mom were from a new generation of liberated women — wait, really?

Unlike Archie’s traditional housewife Edith, who was supporting her husband by making beds and casseroles, Gloria supported her husband as a working girl, behind the cosmetic counter at a department store.

Archie came home from his unionized labor job, sitting in his chair with his wife waiting on him.

Mike came home from a college class and did the same, but with two women waiting on him, while he complained how tough school was.

The Mikes were simply replacing the Archies in the hierarchy. This explained so much of what I saw in my own life. The white college-educated boomer Mikes saw their opportunities expand at unprecedented levels, but society’s expectations of them stayed the same.

Sure women’s opportunities expanded too, in an uneven hierarchical way. But most women saw expectations of them multiply. They were expected to be grateful just to have a job. Just to have a chance to earn a living. Complaining was risky.

I feel like a latchkey kid again. But this time, I’m not only responsible for myself.

A latchkey 40-something

As soon as I became a teen, the boomer gendered power dynamics became center stage in my own life. My high school years were traumatic, immersed in the final hairband days on the Chicago rock scene. I grew further apart from Dad after he moved to Minnesota. But I stayed close with mom and stepdad, until he died the month I (barely) graduated from high school.

I can tell him anything, and he'll still like me

30 years ago, my GenX heart fell for a guy who told me I could say anything, so I asked him to marry me

At 19, I made the best decision of my life and married my artist boyfriend. We built our lives together — college, careers, kids, houses. I felt validated by the admiration of baby boomers in charge. As if our good choices were so responsible and deserving of our conventional success.

But I always knew my life could’ve turned out very differently, very easily.

The meritocracy has shadows, locked doors, and secret passages that keeps some people out, sometimes by design. It divides communities, even families like my own. Places people in boxes on a hierarchical grid, leaving them sorted and stuck. And that wasn’t the outcome I expected from my ‘70s window-to-the-world start to life.

After living in a boomer world my whole life, this omnipresent group is suddenly fading from my day-to-day life. I feel like a latchkey kid all over again–but this time I’m not only responsible for myself. And in midlife, I’m having a growing feeling that I’m not only responsible for my family. I’m still trying to figure out what that means.

The First Birthday After the Death of a Love One

Today is my brother Patrick’s birthday. He would be turning 53, but he died last fall. Patrick was four years and four days older than me. He was a loving and protective older brother who made me feel loved, not in spite of my spunky-kid self, but because of it. Losing a sibling is losing someone who knows your family's precise flavor of crazy like no o…