My older brothers got in the newspaper for modeling denim leisure suits for JCPenney’s. My big brother Teddy’s local claim to fame was doing awesome in Special Olympics – and because he’s the best looking one in the family. My spotlight was for giving Teddy a black eye.

It was 1980 and we were shopping at our local Des Plaines Mall. A local reporter, looking for an “amusing story” for her “Laughing with Lori” weekly column, stopped my mom. My mom never turns anyone away.

Here’s a short version of the story: I kept bugging Teddy, following him around, and trying to do everything first. Eventually he tells me he’ll punch me if I don’t leave him alone. But instead, I punch him first, giving him a black eye.

In my defense, Teddy threatened to punch me first. In his defense, he didn’t actually do it … and I was super annoying. (I’ve since apologized to Ted.)

Hitting someone probably seemed normal to us then because our dad’s response to anything not going his way was to hit, break, or throw. I don’t think he knew any other way. As long as the anger outbursts were at home, it was fine — that thinking was common then.

Corporal punishment was “normal” then too. The Catholic nuns still pulled kids by an ear when my oldest brother Patrick started school in the ‘70s. Luckily for me, the worst I’d get was hit by a flying eraser if I wasn’t paying attention during Music Appreciation or Religion classes in the ‘80s.

At home, spankings, belts, and wooden spoons were considered legitimate forms of discipline. It was the same in many of my friends’ homes too. My grandma Odessa from Louisiana still used switches (twigs from trees or bushes). My grandma Marie from rural Wisconsin washed the sass out of my mouth with a bar of Ivory soap.

The thing is — in most cases — the adults really believed they were doing what they needed to do, to make you “turn out right.” Still, even though it seemed normal then, and I always knew I was loved, it just felt so wrong.

The messages I heard watching Oprah, made me think about how I took care of kids — the ones I babysat, and later my own.

Thanks to Oprah

I'm really thankful that things started changing during our generation. Whatever anyone may think about The Oprah Winfrey Show, I really think Oprah deserves credit for moving the needle away from accepting physical punishment and domestic aggression as “normal.”

Oprah’s voice changed the conversation on early life trauma, showing that when kids are exposed to anger or violent outbursts (even with words), it changes them in harmful ways. Like so many families, I saw the tragic consequences of that play out in different ways over generations.

With Oprah’s reach that continued for years, it’s impossible to imagine how many parents and caregivers were positively impacted by those messages.

Boxed-in by gender

The heavy-handed gender stereotyping is another thing I’m thankful is less common now. I’m described as a saucy, six-year old — “Miss blonde dynamite.”

“What was our spunky blonde up to you ask?” Beating her brother “to the punch,” Lori writes, proving that “blondes have more fun” — clearly cheesy.

To be fair, a writer’s voice is almost always heavily influenced by the time and publication they write for. And cheesy hyperbole seemed to be the reporting style from the time. It sounded similar to a 1978 Washington Post editorial that first coined the term “biological clock.” (I recently wrote about the article after interviewing the Egg Whisperer.)

Today, articles become outdated almost instantly, which means there’s always something “new” to write about.

I remember what it felt like then, being put into a “girl” box with a big warning sticker: FEISTY.

I grew up being told to eat my vegetables to have pretty babies, and my brothers were told to eat theirs to put hair on their chests. The promises of creamed corn or canned peas sprinkled in hydrogenated fat-laden tuna casserole were silly, but the differences in how our behaviors were judged mattered much more.

As long as my brothers were “all-boy,” they had a wide range of acceptable behavior. As a girl, my behavior was described in two ways, summed up by my nicknames: “Devil Woman” and “Miss Goody Two-shoes.”

I really tried being a “nice” girl, but I really wanted as many of those little, colored foil stars from my first grade teacher as I could get. My friends at school were girls full of ambition too. The question was: do you wanna be a doctor, or a lawyer?

Soon we learned it wasn’t okay to show what we wanted. In cheerleading we encouraged the boys to “Be Aggressive” in our chants—spelling it out letter by letter and yelling it out over and over.

But, as girls, we knew that if we showed any hint of outward aggression — even if it wasn’t directed towards anyone — we got labeled the B-word. So we went the passive aggressive route, promoting a mean-girl culture that’s still around today. And those gender biases didn’t end when we grew up.

The year I graduated high school in 1992 was declared “The Year of the Woman.” You knew things were a bit screwy when a single year was dedicated to the majority of the population.

I loved watching Murphy Brown then because her character was unapologetically honest about those gendered double standards. But I also knew that in real life, a bitch label would’ve either held her down or kicked her out.

My experiences were always in sharp contrast to my brothers’ experiences. It seemed easier for them to be openly ambitious. At the same time, it was also clear that they were even more boxed-in by their gender than I was. And they were less protected too; our dad always followed the never-hit-girls rule.

I’ve always considered gender debates centered around one side winning, and the other losing, as no-win propositions.

There’s a real shift happening today. My Gen Z kids are less boxed-in and labeled. There’s a much better understanding of how early life trauma creates cycles of hurt people hurting people (including themselves). Both changes are huge opportunities to break cycles that’ve been generational. There’s something so healing about working toward that, even when there is no “there” that’ll ever be reached.

Making excuses for men

"'My husband, Mike, handled the situation very well as he always does,' bragged Pat (my mom)"—clearly cheesed up like the rest of the story. My mom doesn’t brag, and of course, no parent always handles every situation well. After seeing the the story print, Mom regretted stopping to talk to the reporter as soon as she noticed she’d been misquoted too.

It’s true that Mom frequently covered for Dad’s bad behavior though. Making excuses for men, in general, was a norm—moms for sons, wives for husbands, subordinates for bosses. As a kid, I couldn't understand why and swore I’d never do that. But after having been a mom of little kids, I could imagine doing something similar in a vulnerable situation too, like the one I saw Mom in and other kinds too.

I can also see generational differences too. My parents' marriage dynamics were similar to those of the Mike and Gloria characters on All in the Family. My mom supported Dad through college, the fancy-pants star always in the driver's seat. Like Mike, Dad was the first in his family to go to college. And like Mike, Dad became too big for his britches because of it.

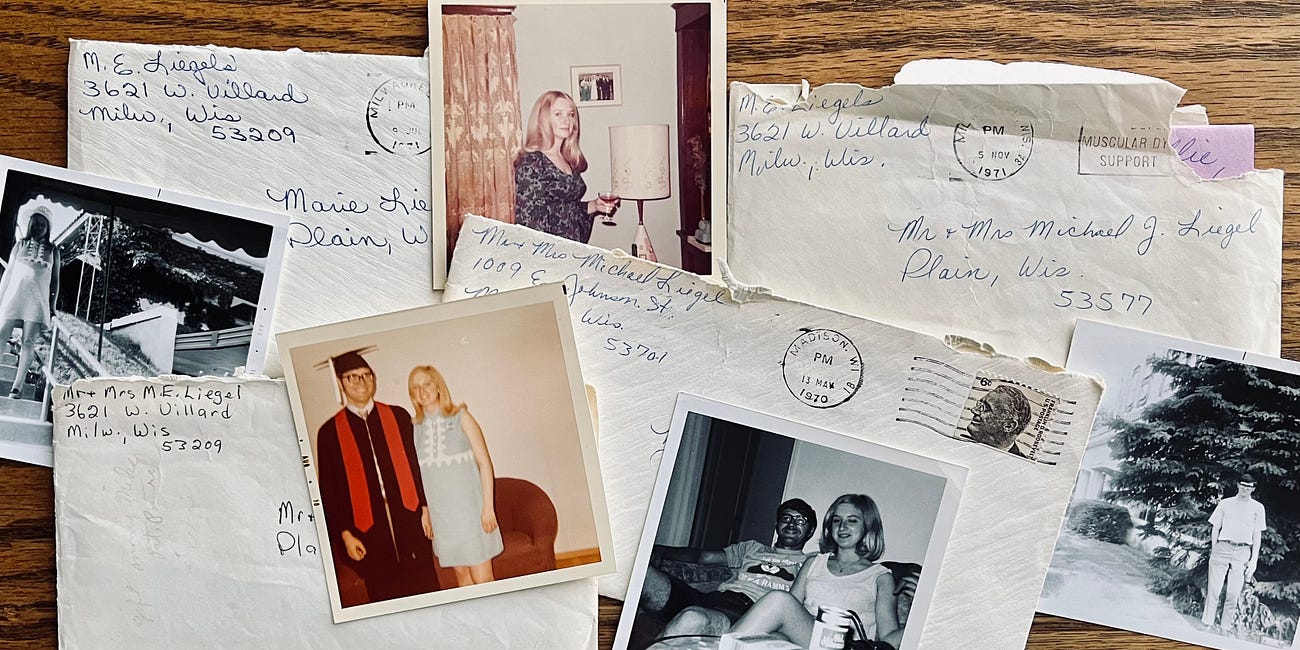

Late last year, I read letters my young parents wrote to my grandma during their early years together. I gained new insight and appreciation of how hard things were for them as they started a family. It got me thinking about how much I really don’t know.

My parents' cost-of-living struggle in the '70s. Why is help still so hard to get?

Hearing my parents' voices in letters from 50 years ago has got me thinking about the impossible choices too many families face. Did the '70s really ever end?