When a parent treats you like crap, why is it so hard to let go?

Sorting through the past: I always knew my brother's life was harder than mine. But I never knew just how hard until after he died.

After someone dies, deciding what to do with the stuff left behind is a long, drawn-out process. My brother Patrick died a year ago. He lived alone and had no kids. We had thirty days to remove his personal belongings. It was a wretched, haphazard process. A storage unit seemed like a perfect short-term solution.

A year later, a storage unit a mile from me is still filled with boxes of papers. Should they get thrown out? Shredded? I feel like I need to go through each piece of paper to decide. But that’s a lot of work … and emotionally exhausting. Which is why they’re still sitting there. I guess Patrick felt that way too. A lot of the papers in his house were our dad’s, still in the same boxes from after he died fifteen years ago.

Note to reader: This is not a happy Thanksgiving newsletter. But Thanksgiving is not always happy. And here I share topics that you might not want to read right now, or ever. I fully appreciate that, but am sharing because I know I’ve benefited from reading other family stories that overlap with my family’s. In that shared story space, it’s comforting to feel less alone.

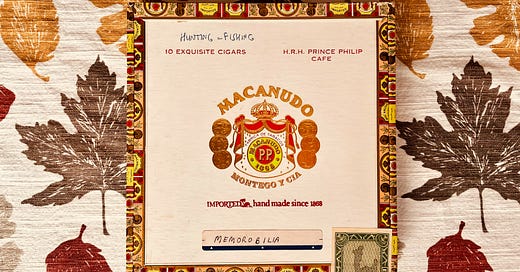

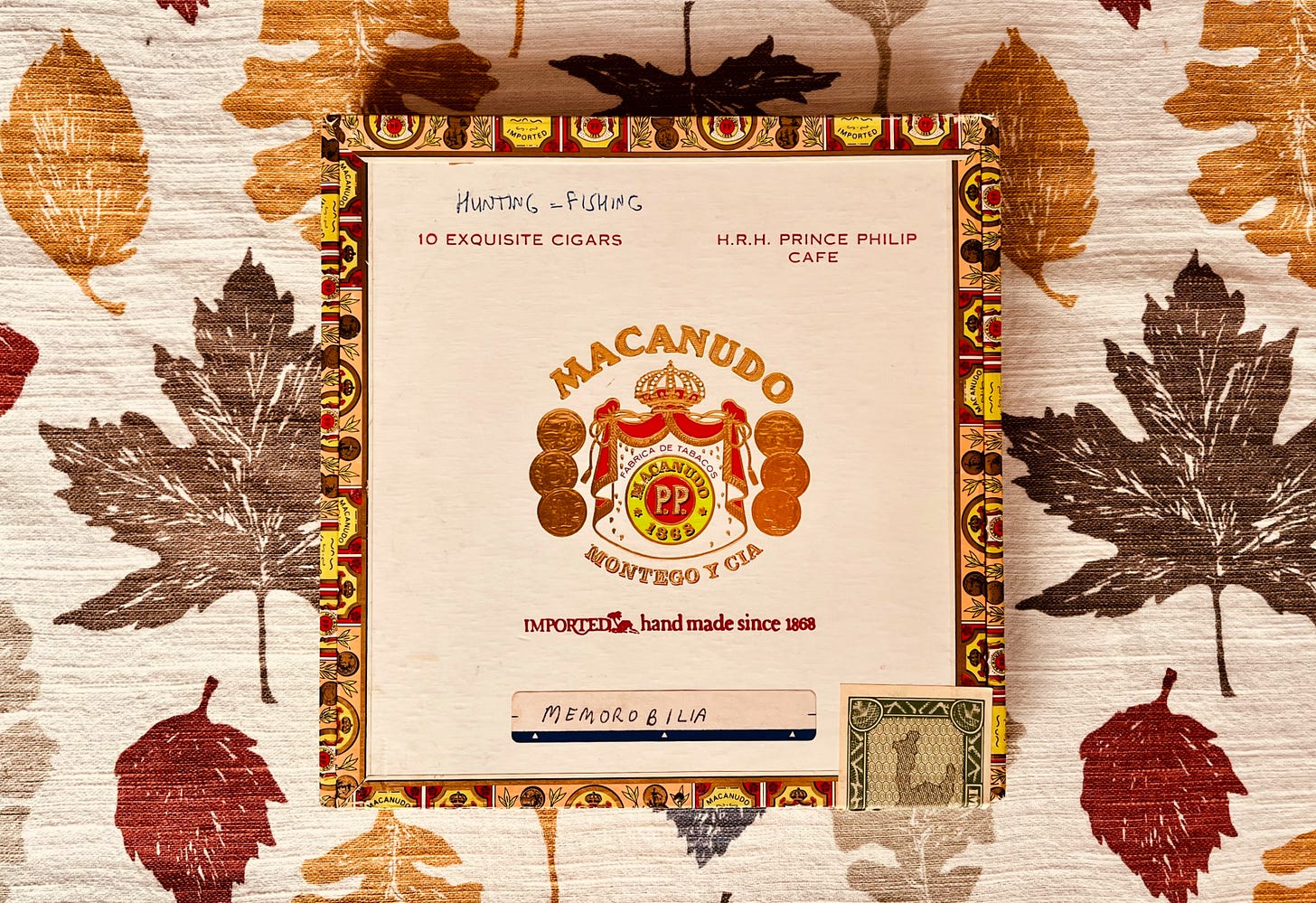

Macundo Cafe Cigar boxes: stacks and stacks

Our dad was a letter writer. Plus, he saved everything. Empty cigar boxes were his favorite place to stash notes and cards for safekeeping. They stacked perfectly and sealed tightly, with a nail included for added measure.

Back in the day, when the thought of spending money on an empty container was appalling—at least to my parents, but I’m pretty sure plenty more—cigar boxes were perfect for small things. My dad gave me empty ones too, and I filled them with my own prized possessions: tiny Barbie pieces, paper fortune tellers, and a collection of Love Is cartoon clippings.

Dad kept stacks of H.R.H. Prince Phillip cafe cigar boxes in closets and cabinets, each filled with tiny pieces of his past he couldn’t part with. Their signature embossed shiny gold Macundo logo and fake foreign bills are etched in my mind. It’s hard not to feel nauseated by the smoky, fumed memories. And it’s just as hard not to miss every bit of my dad’s fancypants, fill-up-a-room presence.

A cigar box with letters between my dad and Patrick sits on my dining room table. I read through the contents last week, and my mind’s still processing them. I know they were intentionally kept with the intent that they’d be read, so I don’t feel weird reading them or even sharing parts of them. Patrick wanted his pain known. Not so someone would feel sorry for him. But so someone would know—really know—some part of what he went through.

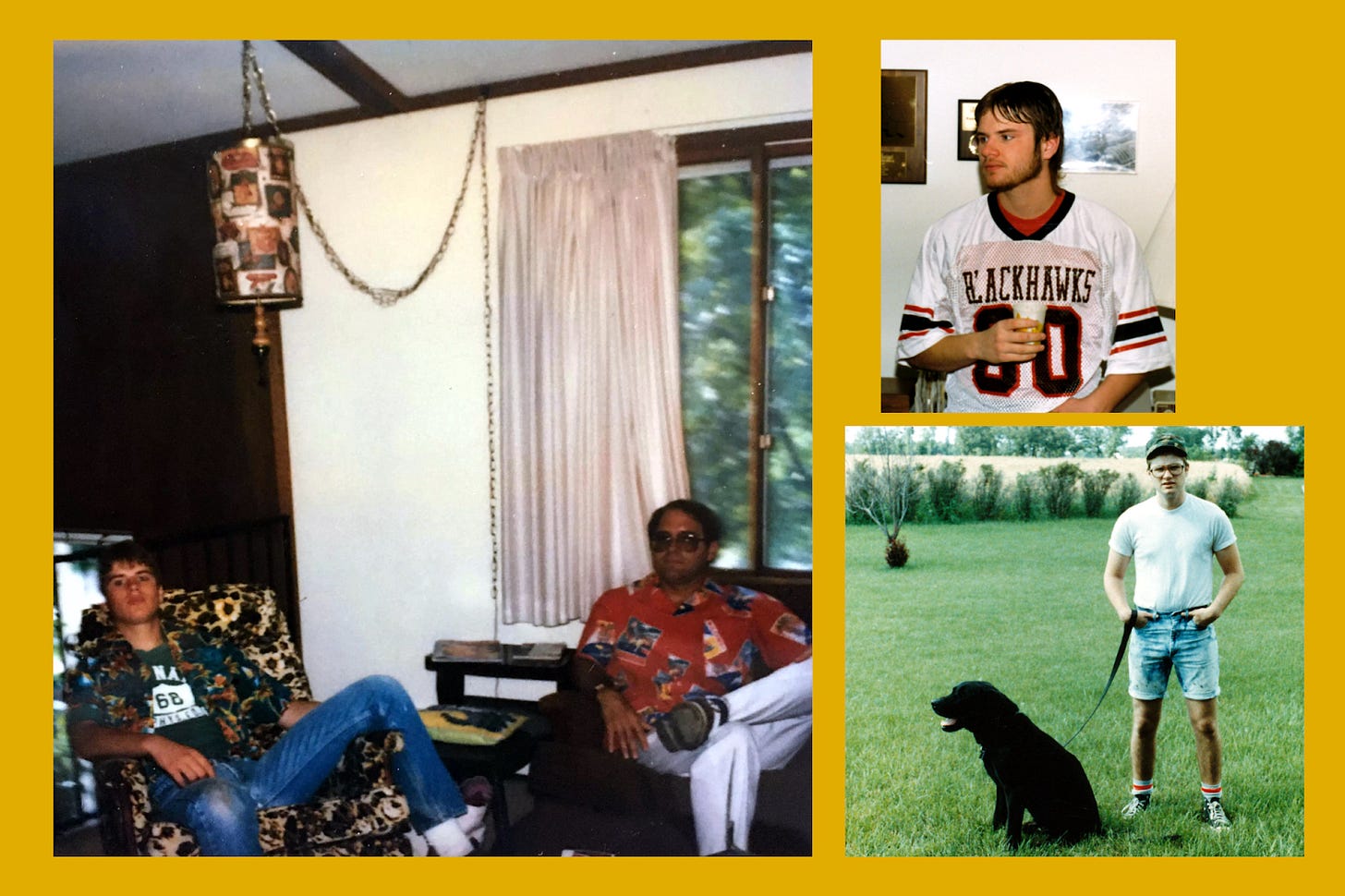

Patrick and I reconnected in our 40s. Never estranged, but separated after our parents divorced — him on Dad’s side and me on mom’s. Through long conversations, we pieced together our pasts, talked about our shared memories, and filled in family stories where parts were missing. We opened up, sharing our experiences of early life sexual traumas.

I always knew Patrick’s life was harder than mine. He was neurodiverse at a time when it wasn’t understood. He was bullied and beaten up by other kids and labeled by teachers who thought he wasn’t trying hard enough. And he entered adulthood in the 90s when being smart with your hands was quickly becoming less compensated and respected — and led to more wear and tear on his body than my “white collar” work. (I’ve never seen hands so scarred and worn as Patrick’s.)

They were more like brothers, with Dad always the alpha one.

No safe place to go

The mistreatment by our Dad made life even harder. Patrick got Dad’s breadcrumbs. He also got punched, blamed, and belittled whenever Dad needed somewhere for his explosive anger to go and stay. Patrick needs to be toughened up, Dad told himself. Lots of parents thought like that then, especially with their sons.

Dad got sole custody of Patrick after our parents divorced, which meant Patrick was on his own, paying his own way at 14. Because Dad never wanted to actually parent Patrick. He just wanted anything he could take away from Mom—and what could cause more pain than losing your child? Dad didn’t realize then, that he would eventually learn that too when I wanted little to do with him.

Patrick went to live with our paternal grandparents during the divorce and ended up staying. He loved the structure and routine of life in the tiny Wisconsin town of Plain, with its Bavarian Catholic farming roots. He learned how to make and fix things. He learned how to make due with what you have. And he cherished time spent with older extended family.

Living with our grandparents provided Patrick with a respite from our parents’ sky-high conflict. But it was replaced by a similar one.

“Grandpa said he is going to move out in two weaks. Grandma said she is going to quit work. And I get yelled at by both of them,” Patrick wrote to Dad.

Then things got even harder. Patrick became a caregiver for our grandpa after he was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. “It’s ruff up here,” Patrick wrote to Dad while sitting at Grandpa’s bedside listening to the transistor radio, asking Dad which rock group was his favorite. Grandma was unable (or unwilling) to deal with caring for Grandpa, so Patrick often ended up being the one witnessing the violent effects of cancer treatment in the 80s.

Dad visited Patrick once a month. He’d take him hunting or fishing. Take him out to eat or to a Badger game. Bring Patrick along wherever he himself wanted to go. And then leave.

“I miss you Dad,” Patrick wrote. “Grandma said she ain’t going to let me live with her any more. She is really mad about something and I don’t know what.”

The saddest letter was between my dad and grandma after Grandpa died, where they bitterly argued about who’s turn it was to take Patrick in. Who’d treat a kid like that? Shamelessly writing about it, matter-of-factly. But anyone in the middle of dad and grandma’s high-conflict relationship suffered collateral damage, even when that person was someone they both loved.

How do you let go and move ahead when you’re constantly pulled back—dutifully answering because it’s not in your nature to do otherwise?

Someone to boss around. Someone to love.

After Patrick graduated high school, he followed Dad to Mankato, MN, where he stayed after Dad moved on. Patrick built a career welding custom car and boat parts. He lived out his passion for racing and motorsports. And he became immersed in baseball as a scout and coach.

Even though Patrick had a separate life of his own with lifelong friends who became his family, his frozen relationship with Dad kept his pain frozen in time. How do you let go and move ahead when you’re constantly pulled back—dutifully answering because it’s not in your nature to do otherwise?

In some ways, if Patrick’s relationship with Dad were mostly bad, it would've been safer. Because Patrick would’ve left, or at least kept Dad at arm’s length like I did. But Dad and Patrick loved spending time together.

They were more like brothers, with Dad always the alpha one. They’d follow their sports obsessions, going to events, memorizing trivia, and debating technical details with the same loud, jovial zest. And when Dad was in a good mood, his gusto, bravado, and high energy were contagious. Patrick wanted to be around Dad. Lots of people did.

For decades, Dad called on Patrick to vent his frustrations, to fix whatever needed fixing, or to do a job that needed to be done but he didn’t want to do. And he called on Patrick whenever he needed to be validated that the divorce was 100% mom’s fault. Membership in the “Mom is evil” club was not optional. There was only one-side to that story. And Dad’s version was brainwashed into Patrick as a child.

Why did Patrick continue staying so loyal? Must be the money, right?— my young adult self thought, looking on from the other side, mom’s side. But Patrick's loyalty to Dad gave him worse than nothing in return.

Is there a phrase for the opposite of generational wealth? Like when the parent screws over their kid?

I knew my F-off vibe with Dad would take away any significant inheritance of mine, but I thought for sure Dad would end up passing some wealth on to Patrick. It wouldn’t even be passing it on, it’d be more like paying him back for years of work Patrick did for him. Work that Dad could’ve easily paid him for then. Money that could’ve helped Patrick finish college so he could teach high school shop classes—his true calling. But I just had no idea who Patrick was then and how much he was like our mom. It would never be about the money.

Trying to understand complex trauma can feel like trying to put jigsaw puzzle pieces together from different puzzles.

Realizing just how bad

I didn’t find out how bad things were for Patrick until after he died. Until I saw how he lived, a place he never let me visit. Patrick’s “inheritance” from Dad was a truckload of picked-through collectibles Dad had spent a lifetime collecting. Patrick was supposed to sell this stuff on eBay to earn a living after his body became too beaten up from welding.

Dad’s stuff became like the breadcrumbs Dad had always given Patrick. And it was all packed into a house no human should’ve been living in. Almost everything inside was Dad’s.

Tweed coats from the 70s. JCPenney diagrams of endcap displays from the 80s. Piles of VHS tapes from the 90s. Records, beer steins, baseball hats. Sports memorabilia beyond imagination.

Worth money? Sure, a dollar fifty here, fifteen bucks there, after the hassle of selling it if you’re lucky. Somehow, Dad made sure Patrick would always be subordinate to him, taking care of his stuff, even after he died.

How do you help someone who’s slowly dying because they feel like they don’t matter?

Too much to carry, too hard to let go

The problem was Patrick was still too enmeshed with Dad to leave the stuff. To walk away from it all, leaving it inside the needing-to-be-torn down home. A house that felt more haunted and unlivable than any I’d ever been in.

I’ll never forget the cold chills I felt walking into Patrick’s home after he died. The 80s hit song “I Wanna Be Rich” was eerily playing on a battery-operated radio, kept on somehow with a fork jammed in it, but unable to be turned off.

The house was creaky, unheated, and lacked safe water. It looked like a jumbled up post-apocalyptic scene with scatterings of Patrick’s welding side jobs and eBay work, though mostly filled with Dad’s decades-old decaying stuff.

Though I never knew it was that bad, I knew Patrick needed help. But how do you help someone who only wants to help others? And how can you help someone when they don’t feel safe enough to accept it? I’m asking these questions because I know there are so many people in situations like this.

If I came across as pushy or dishonestly hopeful, I knew Patrick would stop picking up the phone. And I was the only regular contact he had left with family. There are numbers to call if someone is in a crisis, but what do you do if you know someone who’s slowly dying because they feel like they don’t matter? Patrick felt like another disposable person, near the bottom in our caste system that we’re supposed to pretend doesn’t exist.

Trying to understand complex trauma can feel like trying to put jigsaw puzzle pieces together from different puzzles. Or did it feel like that because the big picture was so awful that my mind protected me from seeing what I didn’t want to see?

Back to Robin Drive

So many of my conversations with Patrick were about growing up in our 2-bedroom townhome on Robin Drive—the only place we all lived together. The last time we all felt loved together. And the last time Patrick was “allowed” to love Mom.

We’d share GenX memories of being home alone and out on our own. (There was something so awesome about that freedom.) And the mix and mingling of families on our block kept life feeling full and interesting. All the differences in background faded away when spending time in another home. The human interactions — parents loving their kids, frustrations that percolate, monotony of the day-to-day — were shared experiences.

Though each unit looked nearly identical, one difference stood out: Could your family afford curtains? That was the question in our mixed-income townhome neighborhood that seemed to separate out families who had enough from those who didn’t.

Our mom grew up on the didn't-have-enough side. Her childhood home had no running water and later she lived in foster homes. She never pretended not to notice someone in need like most people seem to do, like I know I’ve done. Mom let other families use our phone and washing machine, helped people find jobs, and took us to visit and show support for teens on our block sent to “juvie.”

After Patrick died, I heard so many heartwarming stories about how Patrick helped others, in lifechanging ways too. I realized then how much Patrick is like our mom Patricia. His heart of gold was her heart of gold. And sadly, his relationship with Dad was just as dangerous as hers.

“If you don’t have anything nice to say, then don’t say anything at all,” we were told growing up. But bad things need to be said because bad things happen.

Our own family of six appeared as the church-going Catholic family with a college-educated breadwinner father. And we were that family. But we also had police come to break up fights. And we had empty cupboards and utilities shut off during the year dad moved out in 1980, taking his breadwinner paycheck with him.

A 19-year old bartender Mom knew from one of her cocktail waitressing jobs moved in with us to babysit. He made homemade pizza, made extra money selling cocaine, and made out with his girlfriends on the couch. He set up Rocky-style boxing matches between my older brothers. I hid behind mom’s flowy disco dresses hanging in the closet, hearing lots of loud, unfamiliar voices. I learned to cry without making a sound. Pretend I was full when I was hungry. Act like I was asleep when I was awake.

As unsafe as this time period could’ve been for me as a six-year old girl, it was so much worse for my ten-year old brother Patrick. The sexual abuse he suffered by the babysitter’s friend became lifelong pain.

Patrick started pulling his eyelashes out, making up a story that turpentine splashed in his eyes. That sounded hard to believe, but so did pulling out eyelashes knowing how much that’d hurt. But I had no idea how badly Patrick was hurting inside.

“If you don’t have anything nice to say, then don’t say anything at all,” we were told growing up. But bad things need to be said because bad things happen. And when bad things happen to you, and you feel like you can’t talk about it, it’s like those bad things keep happening to you.

Maybe far away, or maybe real nearby

Even as a kid, I knew life wasn’t fair. But even as a kid, I knew it could be fairer. That feeling of “could-be-better” kept me going, explaining why Annie was hands down my favorite early-80s movie. “Maybe far away / Or maybe real nearby” meant possibility, and I loved that song. But it’s hard to have hope sometimes. Within my own family of six, I saw cruelty, some of which I’ll never write about.

My stepdad died after a long struggle with an alcohol use disorder. But the hate Dad suffered from was more destructive than addiction because hate is contagious. And it’s deeply personal.

“So I heard he kicked the bucket,” my dad casually said to me over the phone on the evening after my stepdad’s funeral. “What do you mean?” I replied, confused, shocked, and wanting to have misheard. He rambled on, arguing why my stepdad was a “waste of a life” — until I hysterically threw the phone down, swearing at him.

Right there, on the day of my stepdad’s funeral, Dad expected me to show my allegiance to him by throwing my stepdad under the bus. I threw the phone down to make it stop. But that kind of badgering never stopped for Patrick.

I’ll never understand why tragic events get made worse, again and again.

The weighty now

Sorting through my family’s past and seeing how conflict can live in one family for so long makes me feel like giving up on any feelings of a could-be-better—especially given the current state of the weighty world.

Parents worried about their kids being confronted or hearing horrible things about their family’s ethnic or national origins, religion or culture. People worried about their safety. Ongoing cruel and hateful rhetoric of every kind. Sometimes obvious, and other times not—but with an alarming insidiousness.

Talk of deporting or discounting Palestinian, Muslim or Arab lives, including by some in elected office. Downplaying or ignoring the rising (now spiking) antisemitism. Jewish synagogues and schools needing even more security to stay safe, though still not feeling safe.

I talk with my kids about speaking up in their social circles if they hear anything even subtly disrespectful about other people, cultures, and religions. I encourage them to surround themselves with people who’ll be honest like that with them too. I tell them to seek real conversations with real people who have different perspectives, and then listen more than talk.

But I fear becoming numb. I’m worried I won’t speak up when it matters or that I’ll say something that inadvertently causes harm. And I know that I don’t know … a lot.

“We all meet the same tests,” I recently heard someone say. But that’s not true. Lots of people are facing unbelievable tests at this moment, ones that I can only imagine. Mine pales in comparison: I need to let go of the stuff that Patrick carried for so long. But I know I need to learn something from it too.

Trying to figure out how to let go and move ahead, I listen to Patrick’s coaching voice in my head, prodding me on to do better, believing in me that I can. And I want to use my voice to help others around me feel that too.

Don’t ignore the seemingly subtle

There must’ve been thousands of moments when my dad was a jerk to my mom or brother in front of other people. They looked away, stayed away, or even rationalized it. Or maybe they were too shocked to know what to do or say. I really believe if lots of people around Dad called out his behavior, it could’ve made life-changing differences. Underneath Dad’s bravado was insecurity; he needed some external sources of approval.

I also need to be honest with myself and admit that I paid less attention to moments Dad mistreated Patrick too. Was I too self-focused? Or was it because Patrick was on the opposite side of our family’s divide? Us-versus-them changes what gets noticed.

Watch out, or you’ll become what you can’t stand

After Patrick died, I was so angry, especially at Dad. I pictured all Dad’s stuff in a dumpster fire on top of his Indiana grave. Months were spent like that. And I’ve learned: Don’t tell someone who’s angry to let it go. I needed to let myself feel those feelings.

Eventually, I knew what to do because Patrick showed me before when I was first working through my anger towards Dad five years ago. He helped me see that by focusing on what a jerk Dad could be, I risked becoming more like him. I know that Dad’s wanna-be-right, hyper-focused fancypants is in me. But so are Patrick's and Mom’s hearts. I have a choice.

Pain needs to be seen when it happens

There’s so much I don’t understand. But I do know this: Lots of people are hurting. Pain needs to be seen even if it can’t be fixed or will never go away. Seeing pain matters, and seeing pain when it happens can sometimes prevent even more.

Something unexpected (almost magical) can sometimes happen too. When pain is acknowledged — fully and deeply, again and again — it becomes easier to see other people’s pain.

Forgiveness can’t be forced and it may take time. And maybe it’ll never happen. But it might. I’ve found that place with Dad, holding the good and the bad together and still feeling love, in its full-color splendor. Patrick helped me get here. And that makes “could-be-better” feel real nearby — once and again.

Related reading:

Feeling Badgered by Past Family Trauma

Mourning my brother while missing the '70s—our first decade of life

Staying Alive Inside While Feeling Dead to the World

The First Birthday After the Death of a Love One

Today is my brother Patrick’s birthday. He would be turning 53, but he died last fall. Patrick was four years and four days older than me. He was a loving and protective older brother who made me feel loved, not in spite of my spunky-kid self, but because of it. Losing a sibling is losing someone who knows your family's precise flavor of crazy like no one else can. The same crazy you spend early adulthood trying to escape. But at some point realize you have to make peace with the crazy because it’s a part of you too, in some recombined way.

When Your Dad's a Jerk, Is it OK to Accept His Love?

My dad was an abrasive, unaware, selfish jerk. A sharp contrast with another man in my preschooler life: Mr. Rogers. This man told me I deserved to be treated better than how my dad treated me and my brothers. And because I spent a lot of time in and out of other kids’ homes on my block, it seemed like most kids deserved to be treated better too.

Daphne, this must have been a hard newsletter to write, but thank you telling yours and his story. We have many parallels, as we've discussed in comments before. Be kind to yourself this holiday season.

Feeling all of this deeply. Thank you for bringing the full spectrum of living forward so that “what is” and “could be better” can coexist, in gratitude. 💛