One and the same with your mom—why is separation so hard?

When a parent has a much harder start to life than you, there’s a gift in that: perspective. But it can also make hard things harder to say.

“Just be glad you have a pot to piss in and a window to throw it out,” I grew up hearing Mom say. And I get that.

It’s absurdly silly to think I now live in a home with four flushable pots and countless windows opened only for the fresh air. I know how new that possibility is and how rare it is today.

My mom’s stories have always reminded me of that. And I’ve watched her live her life with a down-on-her-knees appreciation for everything, sounding like a ‘90s Herbal Essence shampoo commercial every time she showers—because she knows what it was like to live without running water.

My relationship with my mom shaped me more than any other. My first feelings of love, loss, and belonging came from her. As a kid, I felt everything I imagined her feeling—and those feelings stuck.

Whatever happened to her happened to me. We were one and the same.

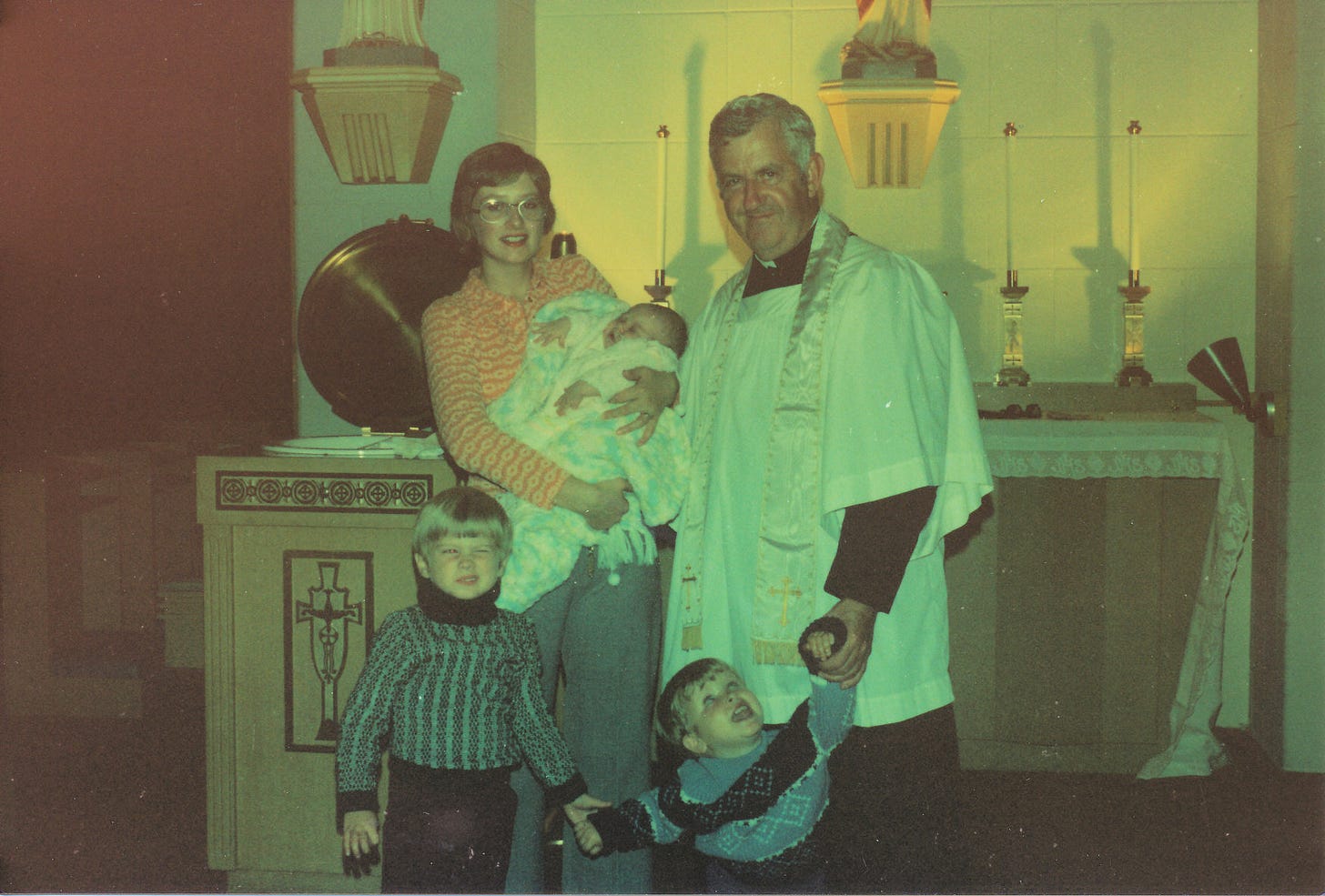

My miraculous mom

I grew up wanting to be exactly like Mom, even while knowing I’d never be able to pull it off. I still marvel at her preternatural ability to only see the good in everyone, everything, every damn day. That alone seemed miraculous, given how her childhood sounded worse than many of the made-for-TV dramas I addictively watched.

In addition to her Doris Day glass-half-full sunshiny outlook, Mom’s generosity was unmatched. She gave away more than she had. Did more than she could. Found the time no matter. Never pretended not to notice a need. And never tried to get ahead if it meant getting ahead of someone else.

People who knew Mom also knew her other side. She was dogged and gutsy, could turn a “no” into a “maybe” then “yes,” and would find solutions down what seemed like rabbit holes, always bringing as many people along as humanly possible.

It was easy being her daughter. But also not.

Day after day, how did she keep giving and living like that? I couldn’t imagine being so nice and doing so much all the time. People liked her for that, a lot. She was the Mom everyone wanted. And our home was the place everyone wanted to be. I’ve always felt lucky to be her daughter.

Try as I might, I could never make myself care about being liked like her.

“What’s wrong with me?” I wondered. “Isn’t everyone supposed to care?” But the problem with caring is caring too much. Keeping the circle small felt safer.

Plus, popularity seemed like pressure to pretend that something mattering to a group also mattered to me—and kept mattering until the one in charge said it didn’t.

Instead, I wanted to be like my mom, like a mirror image that only we saw. Because being totally like the “side” you’re on felt necessary in an us-versus-them family.

Always on her side

For as long as I can remember, I was always on Mom’s side.

Even when I was too young to know why, Mom’s side was always better. Groceries from Mom’s Dominick's were better than from Dad’s Jewel. Mom’s vote for Ford was better than Dad’s for “Farter.” And the Bears beat the Packers no matter the score (though the Badgers were Dad’s true-true fave).

I was Mom’s loyal cheerleader. And I tried being her consoler when my parents' simmering conflict overheated to a boil. I’d run to her bedside or sit outside the locked bedroom on the floor, waiting for what felt like forever. If she left after a blow-up, I’d wait anxiously by the phone, unable to sleep until I knew she was okay. I wanted to know she was okay. But I also needed her to be okay so I could too.

Whatever happened to her happened to me. We were one and the same.

After the divorce, I stepped in as Mom’s ambassador and defense lawyer whenever I visited Dad. I self-censored anything I said to him, making sure nothing I shared could be used against her. I’d casually insert praise for Mom with the underlying hope of convincing him how wonderful Mom is (but yeah, sometimes just to annoy him). And when Dad made any direct attack on Mom’s reputation, I’d rapid-fire as many facts and details in her defense. And then tell him to F-off.

Mother-daughter enmeshment

As I grew older, I became more like Mom’s mirror image.

While Mom was away at work, I became her fill-in, cleaning, cooking, and mother-henning my brothers. And when I became a mom myself, I copied all of her overdoing, momming tasks and tendencies—constantly talking in the same sing-song-y voice; coming up with nonsensical love-crazy expressions for each kid; making the same chicken and dumplings and batches of baked goods; cleaning everything with the same detailed rigor; and arriving at the same conclusions, no matter the topic.

Our feelings were so entangled that sometimes it was hard to tell whose was whose.

Enmeshment felt normal, even good. Then, sometime in the late 2010s, it started changing. Was it the cultural shifting and divisions? My peri-hormones keeping me edgy and up at night? My mom listening to rad-trad talk on Catholic radio? Or me being GenZfluenced by my teens?

Carrying on conversation suddenly felt strained. The obvious differences made me realize something else obvious: I’m not one and the same with mom and never was. In fact, no two people are, not even twins. Obvious things are not always seen, maybe even more so up close.

I started seeing how my whole relationship with Mom was shaped by the underlying us-versus-them complex that dominated everything in our family for as long as I can remember. Resetting my relationship with Mom meant I needed to break free from that. And that meant understanding the other side—my dad’s.

The other side

During the process of getting untangled from my relationship with Mom, I reconnected with my older brother Patrick, who’d been on Dad’s side in our family’s us-versus-them equation. Dad had died more than a decade before. Still, Patrick’s enmeshment with Dad lived on. And at the time, the two of us felt a connection in feeling both disconnected and stuck on our opposite sides.

Learning Patrick’s perspective from the other side helped me find my own space as I separated from my side. He coached me on to write and write some more. And he wrote too. We shared stories back and forth in conversation and text.

While learning more about Dad, I also had to own my watered-down feminized tendencies of being like him. I wrote that side of the story several years ago. There was something freeing about releasing a tiny snippet of our family’s story, doors wide open.

The weight of worrying about someone thinking you came from a “bad family” was so ingrained that I’d never realized how heavy it was. And what a waste. No family is “bad,” and all families have stuff.

But the barriers Patrick had to healing and getting untangled from Dad were incredibly steep. Patrick passed away while still stuck in that painful place. It’s impossible to fully describe what he went through—or for anyone but Patrick to know. But I’ve tried. Patrick wanted his pain known. Doesn’t everyone, deep down?

Hating her and hating myself more

Untangling from Mom was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. There seemed no way to separate myself from my mom without hating her—and hating myself even more. I knew; I tried it before.

“I’d hate being her almost as much as I hate being myself,” I wrote when I was seventeen. I’m sure I was in a mood that day, but I remember that mix of feelings: not wanting to be her but hating any part of myself that wasn’t like her. No matter, I couldn’t stay feeling that way for very long. Soon, I’d always come back to where I started: enmeshed.

One problem with enmeshment is that you lose touch with how you feel, even though you think you know exactly how you’re feeling. Another problem with enmeshment is that feelings lead to over-feeling—on both sides.

What if you tell them something that causes them to feel guilty or even blamed? If you express your feelings, you know you’ll hurt them and feel even worse, so you just don’t.

What do you do if you have “bad” feelings about them—because what relationship doesn’t? Those feelings are so uncomfortable they get buried and build up over time. You may not even know they’re there.

What about “good” feelings or agreement with someone not on their “side”—those feelings are also dangerous to feel, express, or even acknowledge.

Enmeshment may seem okay at first, but then it’s not. And it may be too late to separate before bad things happen.

There is no parent-child relationship when you're one and the same.

My peer-like relationship with Mom worked well when I was a precocious kid. I loved the freedom of not being parented. And she knew I was never the one she needed to worry about. I put myself to bed each night, on time, teeth brushed and homework tucked in my Trapper Keeper, organized for another do-what’s-needed (and then some) day. I brought home A’s and lots of praise—for her, maybe more than me.

But when hormones hit me in high school, not having a parental figure suddenly became dangerous. Mom didn’t know how to say no or set boundaries. And she couldn’t imagine me being anything other than how she’d always known me: someone who knew what she was doing and did what she was supposed to do.

The small red flags turned into big ones. There was no going back. And there was no backstop to stop me from getting into situations I was too young to be in. Once I got through, I never looked back.

Protecting a parent

Thirty years ago, I ripped up remnants, cleaned out closets, and mentally purged traces of my teen years. On the cusp of turning twenty, I was only looking forward, with blinders on by choice. I never thought I’d look back. In fact, I swore I wouldn’t.

Why would I risk facing judgment over things no one deserves judgment for? And besides, who am I to complain? But suppressing my past was also about protecting Mom—from blame she didn’t deserve, but I knew she’d feel.

Why are moms held solely responsible for everything that ever happens in their kids’ lives? That's unfair and unrealistic, and it creates blame-guilt cycles between generations, making painful experiences worse. Instead, parents need more understanding and support, especially during hardship (which may be hidden from view).

Parenting is a crapshoot. Even if a perfect situation were possible, there are no guaranteed outcomes. A lot depends on whether you have the security of resources and emotional support you can share with your child. Community and culture also matter. And we're only beginning to understand the influences of generational trauma.

People carrying significant hurt are expected to do the impossible—and do it perfectly and all alone. That’s how it seems. That even feels too much for me with my four flushable pots.

The facade of perfect is tiring. And in my forties, it started to feel sickening.

The perfect their life never was

When a parent has a much harder start to life than you, there’s a gift in that: perspective. But it also can make hard things that you go through seem like not a big deal. So maybe you don’t think of bringing them up. It’s even harder to bring hard stuff up if you know how happy they are to hear how well you’re doing—happy for you, of course. But also, them viewing your life as the “perfect their life never was” might give their own sacrifices and hardships meaning and maybe even ease their own pain.

This is common. I hear it a lot and know it’s been my experience. Even after I became aware of how much hurt I hid from Mom, I consciously continued the facade because I felt it’d be better for her. But the facade of perfect is tiring. And in my forties, it started to feel sickening. I couldn’t do it anymore. I was done. Done, done, done. Transitioning out of that was really hard and took time.

We don’t have to think or feel the same things. And actually, we never did.

No longer one and the same

It’s taken me a good five years to reach: I’m not her; she’s not me—and that’s okay. Mom and I are still close; but it’s a different kind of close that’s healthier for both of us. When needed, we agree to disagree. Some topics are still too divisive to discuss, but not all and not always.

I’ve grown to accept that we don’t have to think or feel the same things. And in fact, the total alignment I felt before wasn’t even real. Sometimes Mom was reflecting back what she thought I wanted to hear because it seemed easier than saying what she really thought. Other times I was still a kid pretending I was her.

Mom’s experiences that I imagined and felt as my own were never mine. They are hers and only she knows. I listen and learn from Mom—and of course, our stories overlap—but I need to understand our perspectives are different. Likewise, my life is not a measure of how good she is as a mother or person. I'm so over the “perfect mother” myth that creates unrealistic expectations and perpetuates blaming and shaming.

Now and ahead

I’m almost 50, and finally, I’ve stopped feeling the need to be just like Mom. Just like me is enough.

I still absolutely love Mom. And I want to be there for her in whatever way she needs and wants as she moves through her later years. Mom's been the best teacher I've ever had. And many of her lessons are growing deeper in meaning as I grow older. But I’ve also worked on unlearning some that haven’t helped me be a better me.

My mom and daughter Nora are also close. We lived nearby while Nora was growing up so they spent a lot of time together. I often say Nora is the fun daughter Mom never had. But Nora’s grown and off creating a life of her own. So I try to stay in my own relationship lane with Mom and respect Nora’s relationship with her as separate from my own. I’m not saying I always do that perfectly, but that’s what guides me.

I’m hoping not to repeat the same enmeshment pattern with my daughter (if I haven’t already). But relationship repair is needed at some point in every relationship. And it’s ongoing. There’s no all-figured-out and done. So I’m trying my best to respect and support Nora (like my mom has with me), even when there are uncomfortable things for me to hear. It’s all okay to say.

Stories coming up:

“Picking a side, the always-present past, and rad-trad what? That's family for you” — it’s a story about a panic attack I had at the doctor's office 5 years ago and the growing Catholic cultural divides within my family.

In “Writing my way forward” I talk about why I started writing and why I'm not stopping now. Plus, thoughts on healthcare anxiety and slowing down the discussion at the doctor's office.

I’m watching Little Adventures. My middle son became obsessed with this show during the pandemic, so I already have Julia’s voice etched in my brain from hearing it in the background. But now I’m watching it in preparation for the two guinea pigs he’ll be getting this summer.

So You Became a Mom

Three big things happened the summer I turned 14. I found out my aunt was pregnant. We finally got MTV. And the 1988 summer heat wave convinced my mom and stepdad that A/C was a must-have. With high school about to start, my life seemed to be on fast forward.

The strangeness of being in the middle of your mom and her mother-in-law

Mother-in-law and daughter-in-law relationships are complicated, even more so after divorce. I was stuck in the middle — between my mom and dad’s mom — for decades. I felt fragmented and wondered: Why are the women who stay sometimes the first to judge? Why do they set the standards other women are compared to?

What an important essay. I wish every mother-daughter could read this. I remember the moment when I finally differentiated my experience from my mom and it took forty years to get there! I found it interesting also that first, in order to separate from your mom you, you had to look at how things lived for your dad. And then I’m assuming ultimately that freed you to finally discover your own thoughts and feelings. Thank you for sharing this intimate and enlightening piece!

This is SUCH a good piece. There's a few people in my life — both women and men — who I know could benefit from reading it. Will try to figure out how to get it in front of their eyes...