Why do other people tell your story first?

After a panic attack at the doctor's office five years ago, I knew I needed to untangle my story from my family's and tell it as my own.

Getting away from chaos at home was always my incentive to grow up and grow up fast. And by the time I turned 18 in August 1992, I felt more than old enough.

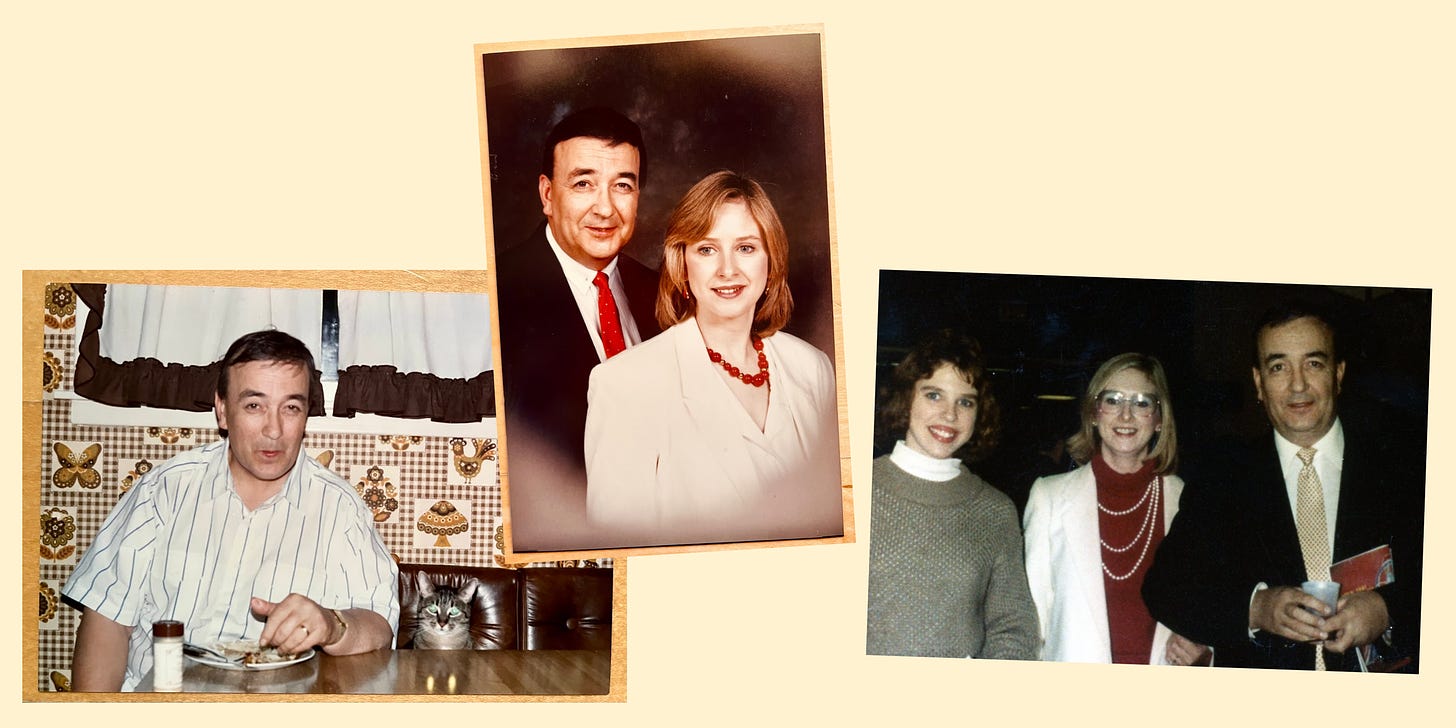

My stepdad Gene just died in May. It wasn’t unexpected. He’d been terminally ill with a failing liver for some time. But after a few years of living while dying, death starts seeming less possible. So when it happens, it still feels surreal, and sadness still feels heavy.

Gene was someone I didn’t want to like when I first met him in 1983. But he was also someone I couldn’t help but like and eventually love. Gene didn’t have the problems most men I knew seemed to have. He wasn’t weighed down by a fear of not being “man enough.” He wasn’t intimidated by smart women. And he adored my mom.

Gene was also a realist, and knew the grittier side of life far more than most. He knew things were gonna get bad for us after he died, knowing he’d be leaving behind medical bills my mom would never be able to pay. So a month before he passed away, he gave me a singles brochure for an elite mega-church.

“Marrying well”

I knew “marrying well” was thought to be a girl’s best option when Gene came of age in the 1950s, and I knew his sharing this was well-meaning. I also knew “marrying well” wouldn’t go well for me. For someone else? Maybe. It’s not my business who or why consenting adults marry. I knew what I needed to do to be well. I just needed to make enough money to take care of myself.

Figuring out where to go in 1992 wasn’t easy. Smugness here, posturing there and senseless situations everywhere. And where could you go where your body would be yours? I tried to numb myself by stuffing myself with Snackwells. No good ever seemed to come from feelings.

During the day, I was taking catch-up classes to officially graduate high school that month. At night, I was a hostess, asking guests which side of the smoky room they wanted to be seated in.

I didn’t mind the job. But I didn’t get enough hours and I was desperate for money. Not dirt-level desperate enough to go to Dad, but look-for-change-under-couch-cushions desperate to buy things I desperately needed—community college credit hours, gas for my Ford Tempo, and fuel to keep me going: cigarettes, cereal, and skim milk.

Life-changing job

Each week I’d scour the want-ads. Then one week I saw a posting for “activity aide.” I had no clue what that meant, but “no experience necessary” and seven-something an hour pay sounded good. The job was at a residential home for people with developmental disabilities.

My first day was a sensory overload shock: people crowding my personal space, dozens of different interactions all at once, and the continuous sound of Richard Simmons’ “Sweatin’ to the Oldies” VHS tapes mixed in with a random piercing scream. I didn’t know what to do or how to help.

Had I not been desperate for money, I might not have shown up again. But I did, and it was life-changing for me—not only because it’s where I met my husband, who also worked in activities. Working there made me think about who I wanted to be.

I felt so lucky each day I spent there, getting to know each person who lived there. There’s a sameness in people beyond the surface-level differences. It’s grounding and connecting, but easy to forget when you don’t have enough regular opportunities to feel it. I felt honored to be there. Working there also made me think about who I wanted to share time with in my personal life.

I can tell him anything, and he'll still like me

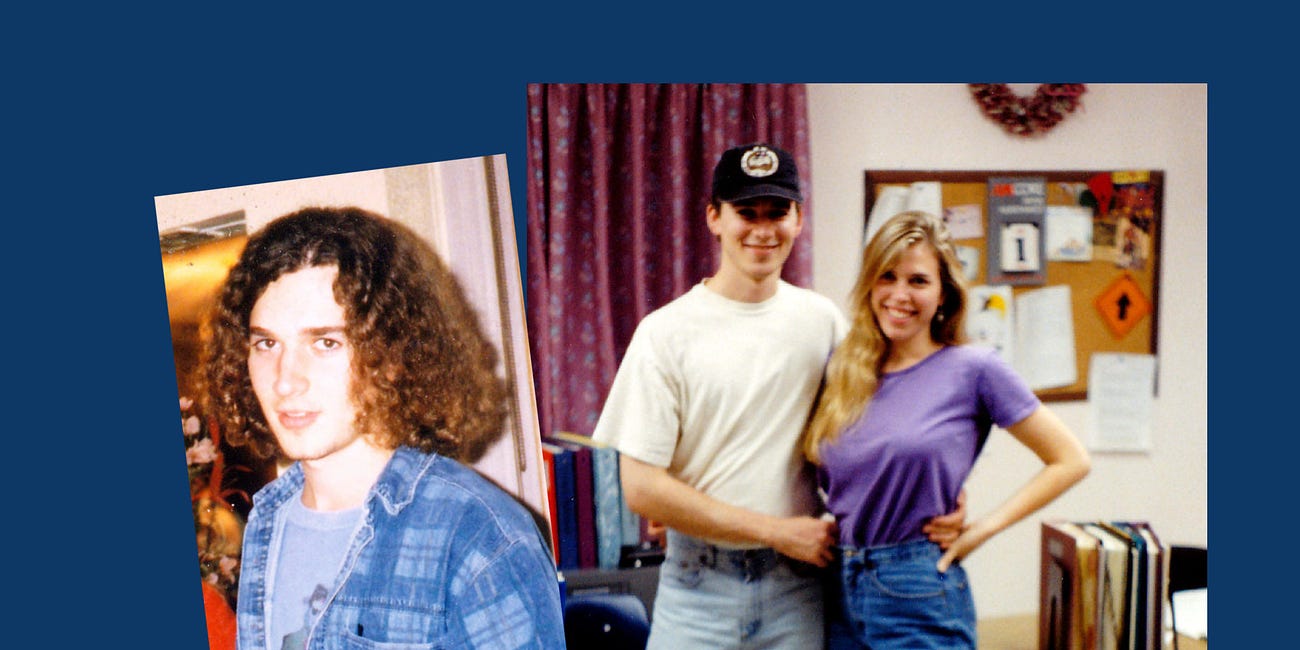

Brian had Kenny G curly hair, pulled back in a low ponytail. He wore flannels over cartoon character t-shirts. His car was cheap and his brown suede high-tops were held together with duct tape. Working in community theater, taking every creative class offered at the community college, he happily went about, finding his own space within the same bad-boy 90s I felt stuck in. His confidence in simply being himself totally fascinated me. I never met anyone like him before.

My husband’s mild-mannered, artist soul drew me in with curiosity and desire. He had the top two traits on the must-have list I made for any dating prospect early in college:

Open-mindedness—because I wanted someone to change with.

Being nice to other people—seriously, it’s hard to know if someone treating you nicely when you first start dating has anything to do with who they really are.

But Brian also had something I didn’t think was even possible. Unlike myself and everyone in my family, Brian wasn’t some reactive mix of “fight or flight.” And it wasn’t just a calm and collected side he put on when he needed to. So when I realized he was for real, I asked him to marry me.

Leaving home, but not getting away

I married Brian at 19, and it was the best decision I ever made. I sometimes wonder if the “wait until you’re old enough” has gone too far for young people, especially when it comes to real-life experiences. I don’t remember needing a nudge to jump in, try something new, or move on. Everything was trial and error, figuring out a way to leave home.

But leaving home doesn’t mean getting away. No matter how long it’s been since you left, you hear their voices in your head. Their imagined reactions shape your choices—whether you know it or not. Then, at some point, you realize some of their most annoying habits are in you too, drawing you back to places you couldn’t wait to leave and are now leaving your life in limbo. The past is always present.

How can we stay together without feeling stuck?

And how can we separate without falling apart?

An EPIC life summary

Why is such simple separation so hard for so many to find? Because I know my family’s not alone on this. Separateness is such a sticking point in relationships and life—until a turning point.

Mine came during an annual doctor’s appointment five years ago. We’d recently moved, and I was new to the practice. The medical assistant brought me into a windowless exam room, sat me down, and strapped a blood pressure cuff on my arm, leaving it in place while she gathered my full medical history.

While typing and talking, the assistant’s eyes darted back and forth between me and a screen filled with a familiar-looking EPIC chart layout I knew from work, but one that feels very different when I’m on the patient side.

Up on the top left, there’s my tired-looking, oddly-lit face in a circle. Just below is my overrated BMI. Directly left is my expanding list of weirdly-worded “problems,” kitty-corner to a graveyard of my relatives’ death dates, conditions, and diseases.

Scroll down further: any vice I have had, now have or might have. And a little further down to a list of everything I’ve ever known that’s ever happened inside my uterus: one abortion, two miscarriages, and four pregnancies that turned into four live births, which got charted with names.

There’s something so weird about spilling secrets summed up in seconds to a complete stranger. But the problem with sharing so much so fast is it can easily lead to oversharing—at least for me. And the moment I start talking faster, it’s probably too late.

I can’t remember exactly what I said, but I’m sure it had something to do with the latest family drama at the time over my daughter’s coming out (which was old news to me) but new (“yeah, we knew”) news to some of them.

I felt un-belonged by my side—a side I no longer wanted to belong to.

Alone at the cafeteria Catholic table

While most family members fully supported our daughter, the Catholic cultural divides in my family were widening alongside the culture writ large. And the rad-trad route wasn’t one I wanted to follow. No God’s will voice told me I should. And my own voice told me I should not.

“You can’t be Catholic and support your gay daughter,” I was told. I felt un-belonged by my side—a side I no longer wanted to belong to, but I still felt like I needed to. They were “my side” in our us-versus-them family. They were my safe place. I just needed to get them to see how deeply hurtful (and damaging and nonsensical and hypocritical and …). Then everything will be okay again.

But as time went by, and little changed, I became filled with raw, mama-bear anger over something that’s nobody’s business and that I couldn’t even imagine mattering, especially in the 21st century.

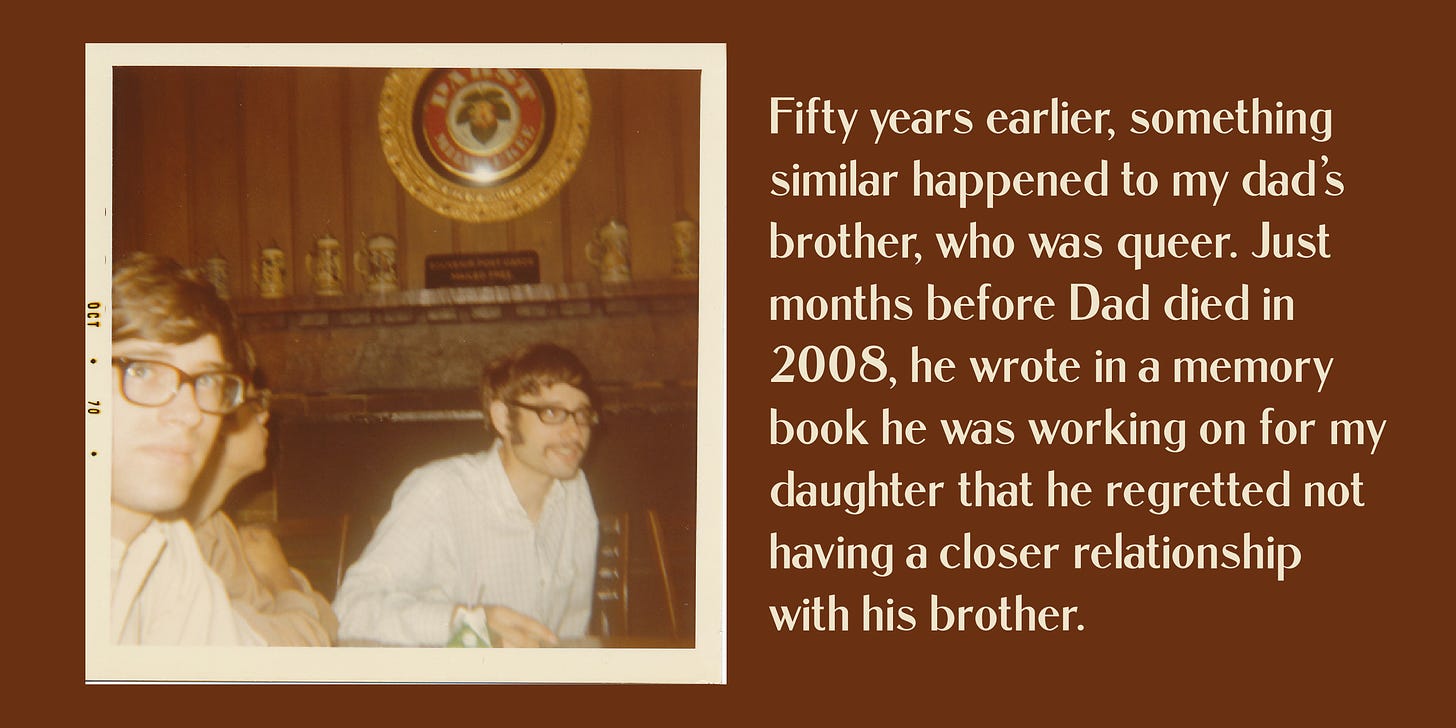

Why does history keep repeating itself? I like remembering the past, but mostly to remember how much it sucked. And to learn from it.

Biblical debates aside (I’ve learned to never, ever engage in those), THIS felt deeply personal, hurtful, and abandoning. And soon, it snowballed to include inferences about my Baháʼí-raised, now agnostic husband, my tumultuous teen years, and even how we raised our kids. THIS was about MY family, the people I live with and love. (And all of this happened before the topper—2020.)

Exam room panic attack

Feeling embarrassed for wasting precious healthcare time babbling about my life problems, I shut my mouth. My attention shifted to my arm, now numb and hurting with the blood pressure cuff still in place. It started feeling tighter and tighter, but when I looked down, I saw it hadn’t started.

I looked up and said nothing but sensed she was trying to make sense of my secrets by turning them into a story of her own about me.

Though in retrospect, this probably wasn’t the case. She was probably thinking about how to get on to the next patient, what to eat for lunch, or something about her kids. Whatever it was, it probably had nothing to do with me on a personal level. But in that moment, everything felt personal and tied to something I felt before.

It’s taken me years to separate out what I was feeling at that moment. Like all life stories, mine are filled with deeply felt and deeply private experiences, with layers of granular details and overlap too complex for even me to understand.

Stories are complicated. And when they get pulled into family divisions fueled by cultural divisions, there’s no making sense of anything anymore.

The rad-trad stuff brought out anger over sexual shaming—from Dad’s mistreatment of my mom to my high school slut-labeled days to my own daughter's identity. Three generations of bullshit (and generations behind us). Will it ever end?

Talking about Dad's death flooded in mixes of missing him with feelings of resenting him and guilt over not saying things I wish I’d said.

Documenting my past abortion fed into fears of having my personal and private medical history used to feed into narratives with divisive or political motives—which felt invasive and deeply disturbing with worrisome consequences.

And my sense of disconnection from my family reminded me of my runaway teen years when strangers forcibly took me out of my bedroom in handcuffs and sent me to a psychiatric hospital.

I felt it all, everything, all at once.

I knew that feeling of having my story told by others, so much so I spent my teen years existing in monotonous disconnection from life. But I also felt connected to others through feeling disconnected, knowing they knew the feeling too. Maybe disconnection is more the norm than the exception.

“There's a woman on the outside / Looking inside, does she see me? / No she does not really see me / 'Cause she sees her own reflection” - song lyrics by Suzanne Vega, “Tom’s Diner”

As the intensity of my pulse grew within my squeezed arm, spreading throughout my body, I started hearing the rhythmic sound of “Tom’s Diner” playing in my head, just like I’d heard playing on my car radio in 1990—the day I drove right past the Sugar Bowl diner where my shift was about to start. The day I kept driving and driving until I almost didn’t come back.

When the medical assistant finally pressed the button, and the blood pressure cuff began inflating, squeezing tighter and tighter before cresting, I had a full-blown panic attack. My old teen selves were with me, along with their memories of rape and restraint. Like broken-into-bits Matryoshka nesting dolls, they’d been hidden away, broken and trapped inside. And they’d been broken and left abandoned by me.

I knew I had to put them back together and tell their story as best I could.

Telling my story myself

Writing has helped me feel whole again, and it’s made a big difference in my life and relationships. The process was self-focused at first, but the better understanding has grown into more compassion and levelness for everyone.

I’ve stopped putting my stories into ones that aren’t mine—or at least catching myself when I do. I had no idea I even did that. I’m also much more aware of how telling stories from the outside looking in is often wrong, hurtful, and disrespectful.

Owning my story also means owning my parts, including the ones I regret.

“Just don’t pick up the phone,” my husband would tell me when drama flared. But for the longest time, I did. I couldn’t help myself. What kept sucking me in and pulling me back to places I didn’t want to go to but went to anytime the phone rang? I really didn’t know. The sadder part wasn’t that I went; it’s what it took me away from.

“I’m gonna be the best damn gay mom I can be,” I told my daughter after she came out. But my daughter didn’t need a “gay mom” fighting fights that oftentimes had nothing to do with her. She just needed a mom. And I deeply regret the times when I chose drama over presence.

It’s true I needed to show clear support for my daughter and set boundaries with some people in my family. But I can see now that most of the family drama wasn’t about her—or me as her mom. The drivers of the conflict started years ago with our family’s us-versus-them dynamics and each of our own shoved-down painful pasts.

Bridging the past to next steps now

Writing was my way of figuring out a way forward, but it doesn’t have to be writing.

I’ve seen people find ways through in lots of other ways—music, movement, faith rituals, making new things or new connections. Really, anything that helps you tap into your feelings and bridges you into moving ahead—one step, then another and another.

For most of my life, I’d say “I’m fine” reflexively to everyone. And even if I did admit having any problem, I wouldn’t be able to articulate why. Anyone who needs help deserves it—no questions asked. I needed professional help during the process.

Having a neutral, trained person there when the floodgates open is important. Mental health issues are very common and treatable. It also helped being selective about who I turned to for personal support. And in some cases, I needed distance from some relationships while working through stuff—that was really hard to do.

The Avalanches’ 2020 album We Will Always Love You was so healing when I started this process. Each song is a mix of sadness and hope. Figuring out how to hold those together is the way forward.

What’s next?

I'll go deeper into my family's Catholic cultural divide in an upcoming post and discuss how I'm managing family conflict. In another post I’ll discuss healthcare anxiety and biomedical ethics (one of the most useful college courses I took).

I still plan on writing a “troubled-teen” psychiatric hospital story, but am waiting until next winter. My memories are strongly connected to the season they come from. This summer, I want to write about the 1990 Pretty Woman “bad girl turns good” fairytale and the toxic takeaway messages I took in the summer I turned 16.

With our oldest son graduating high school, I’ve been thinking about how much harder it is today to get through college without parental help. Like a lot of Gen Xers, my husband and I did, but the numbers today are on a whole new scale. Getting through the “weeding out” process seems a lot harder too.

Referring to people as weeds itself is repulsive. Symbolism aside, do the cutoffs and scores really determine who’ll do well when it matters—after college? I don’t know, but it does seem like a lot of fields narrow who enters them by making the perquisites stricter than they need to be based on what’s required to do the job. What are the downsides to funneling people into different professions? This I want to write about too. But like all writers, I have way more ideas than time.

Related reading

America’s Mental Health Is Worsening. Special Urgent-Care Clinics Step In by Stephanie Armour. A psychiatrist I interviewed this week mentioned having one of these in the health system where she practices.

‘A step back in time': America’s Catholic Church sees an immense shift toward the old ways by Tim Sullivan. This article hits home—in my heart and family. Some Catholics I know feel judged for living according to their religious traditions. That shouldn’t happen to people of any faith. But it’s possible to be respectful of individuals while voicing larger concerns and asking questions.

What happens when strict and total alignment is expected within a group?What happens when religious beliefs are imposed on people outside of the faith?

If you have concerns, speak up. If you have stories that need to be remembered, share them. Those are important Catholic lessons I’ve learned and they apply to any group belonging. I’ll write more about this in an upcoming post.

One and the same with your mom—why is separation so hard?

When a parent has a much harder start to life than you, there’s a gift in that: perspective. But it can also make hard things harder to say.