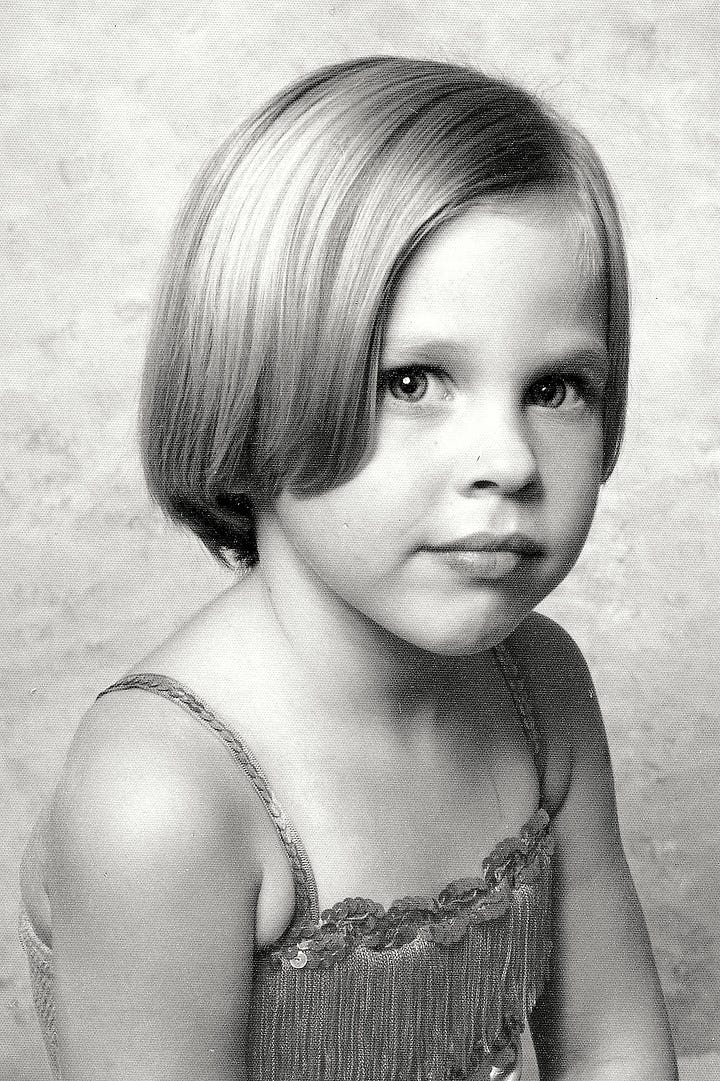

It’s striking to see aspects of your essence in another person. It can feel comforting and connecting. Or it can feel unsettling. (Do I really wanna see every aspect of myself reflected back?) Sometimes, finding points of commonality can be life-changing. I’ll never forget the moment when I knew I wanted to be with my husband.

While seated at opposite ends of a long pub table in a dimly lit pizza pit, our eyes wandered to each other, bored by the conversation among our college-aged co-workers. We saw our own thoughts in the others’ eyes and knew both craved conversations no one else there would understand in the way that we did.

With kids, those moments of connection are bidirectional. Adults see their past kid selves and kids see their own future ones. The more similarities, the more real the visions feel.

“We had a pop-up quiz today, and one kid started crying, so I ripped a tiny corner of my paper,” one of my kids once told me. I knew exactly what he meant and could picture myself doing the very same thing at his young age (and probably did). Hearing someone hurt and not being able to help hurts too. Ripping a piece of paper would release a tiny bit of that tension. It’s not easy feeling like a sponge.

Like my kid-self, he’s also the one who loves with an earnest intensity, is crowding and curious, and seeks out every sensory input, detail, and fact about life and a past that mysteriously still feels present. If you’re gonna absorb everything, figuring out how to make sense of it all feels necessary.

Crowding and curious

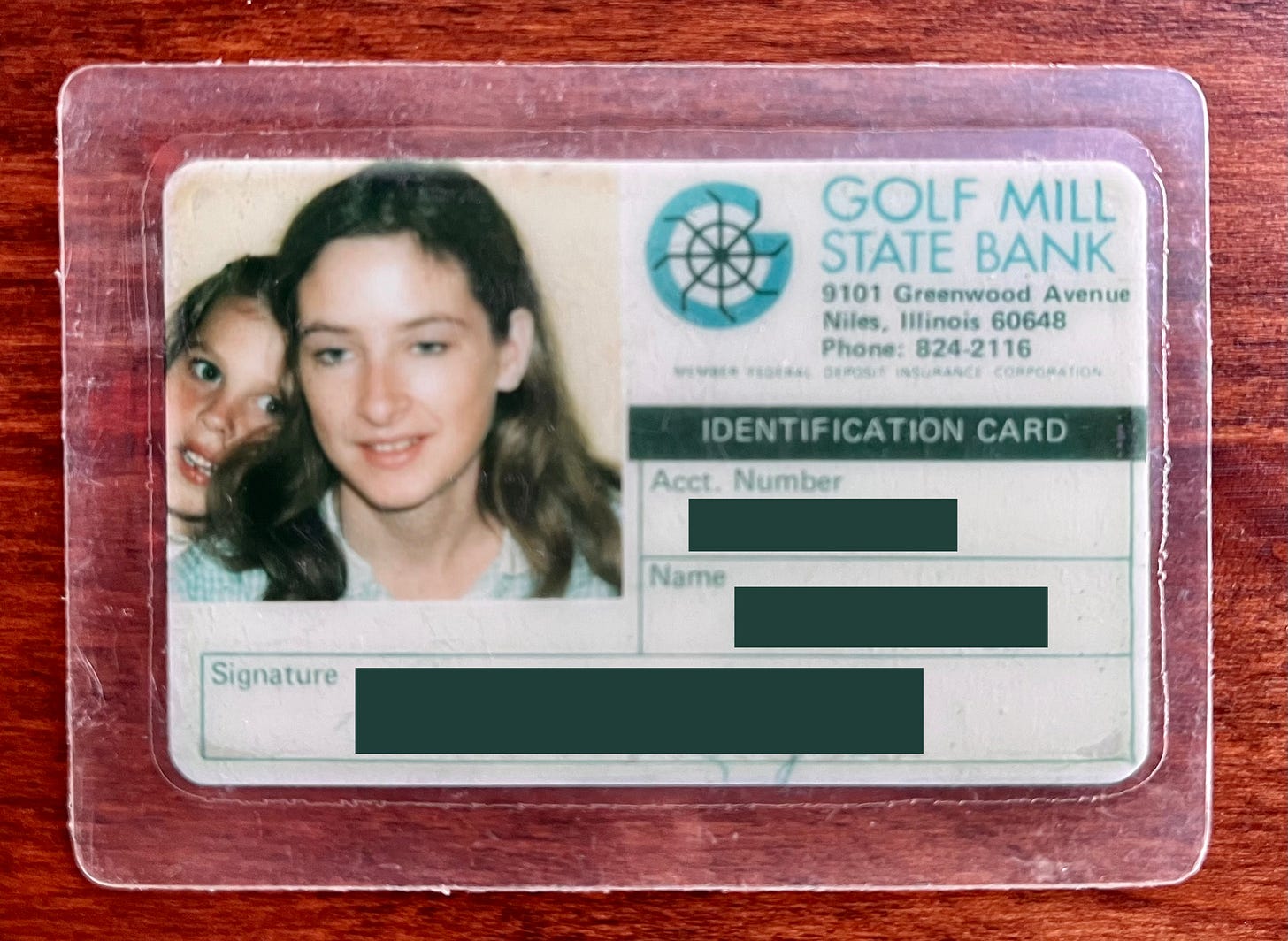

Years ago, I put Mom’s outdated bank card ID in with my keepsakes. It was one of the few pictures I had of me and my mom, with our faces close, like I remember them being. I remember Mom looking tired, but the fatigue in her young face is striking when I look at photos now. Was it from years without sleep? Years married to a man with anger issues? Years of doctor-ordered Valium (at doses of 35mg)? Or maybe anemia or endometriosis or all of the above (plus more)?

Mom’s bank ID photo was evidence of how I always had to be right by her side, determinedly so—I’d hear Mom tell other people, laughingly, and with a tad bit of pride. It feels good to be wanted. And Mom made me feel wanted too. I knew I meant the world to her. And I knew her being there for me and my three brothers also meant the world.

I used to think I grew up hearing so many family stories because I come from a family of storytellers and over-sharers. But I’ve also realized it’s because, like my son, I followed the grown-ups around, asking questions and always wanting to know more.

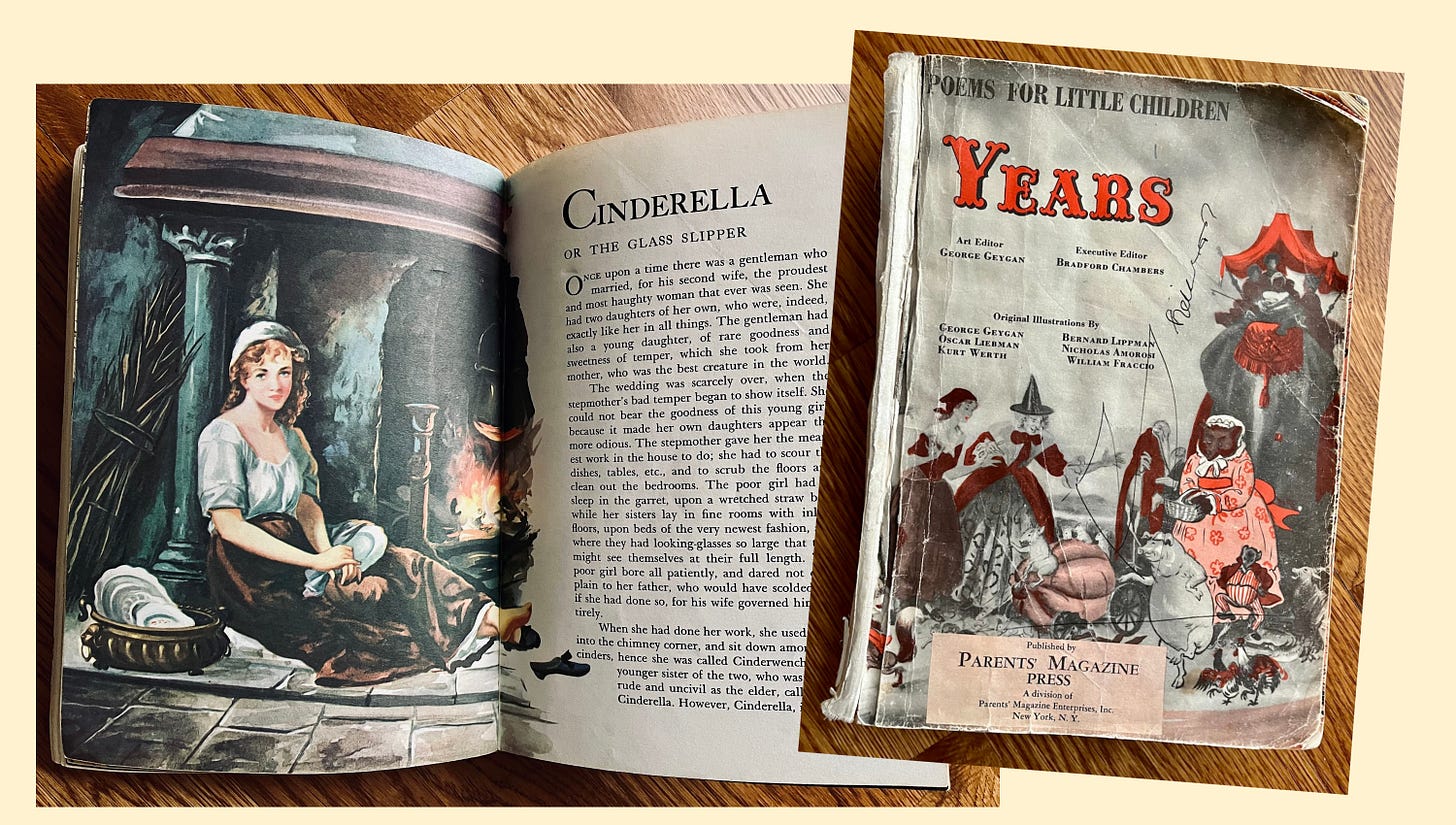

Luckily for me, my mom was a fantastic storyteller. We had one well-worn 4-inch storybook she regularly read from when my brothers and I were young. If you grew up in the 70s, maybe you had the same mass-produced copy too. If not, you’re probably familiar with the generations-old fairy tales and “poems for little children” about the cruel world and lessons to survive in it that were sometimes worse than the cruelty itself. But I get why they were told with similar versions in other cultures. Fear from story was far better than having no fear in an unsafe world with no safeguards. The problem, though, is the undesirable byproducts that fear brings.

Mom sat in a spindly chair, tiny by today’s standards, and we’d gather around on our bedroom’s parquet floor. Calmed by Mom’s voice, hearing stories made me feel taken care of in a way I’ve never grown too old to want. She narrated with cheery warmth and measured rhythm. She made up voices that perfectly matched each character and kept their voices sorted out from start to finish. The best part was how she built curiosity, knowingly accentuating key plot points with the grandeur flair of a British mystery.

The same stories never grew old. Cinderella was my favorite. She reminded me of Mom—gentle, unassuming, and helpful. Kind to all no matter what. Doing the drudgeries with the same sing-songy, sparkly-clean magic. In one stroke of a dish rag Mom could catch every crumb, smudge, and sticky spot. She scrubbed and rubbed and polished until every surface glistened and gleamed.

A chance to get out and away

No matter how shattered and soiled life got, Mom wiped away tears, picked up the pieces, and put it all back together while consoling and assuring others, “It’ll be okay.” The ease of the words left me with unease too: Why should it be okay?

The unfairness of adulthood heightened the appeal of adolescence. Teens were so other-worldly cool. “What a great time in life. The perfect time,” I thought. Having a chance for something better had to be better than no chance at all.

I’d watched my babysitter dreamily trace “I ❤️David Bowie” on the sides of her high school textbooks, displaying her devotion greater than any fine to be paid. I’d ask what she was doing when she underlined her eyes in electric blue and concealed her zits in Maybelline beige, and then needed to know what zits were. I learned how handkerchiefs helped hide hickeys, and upturned collars could low-key display them.

Being a teen meant having a chance to flip the script or get a better hand before getting stuck in situations with no easy through or out. I couldn’t wait for my teen girl curves to elevate me above being a “dumb kid” with little to no choice or say. And if life at home ever got bad enough, I wanted my chance to get out and away. Just like Cinderella did. And just like my mom did as a teen herself.

BUT I never wished to be swept away into a castle. That sounded more nightmare-scary than dream-like. I knew happily-ever-after could turn into a heart-wrenching prison sentences, and I wouldn’t wanna be stuck in a castle if it did.

Friends with mom

“When the lights are on, people might be watching you without you knowing. But when the lights are out, they can’t see you,” Mom explained as she turned off the bedroom light one summer night. I was scared of the dark until Mom reframed darkness as safety. But I was still scared of being alone in bed.

I feel bad now thinking about how many times I climbed into her bed, squirming in next to her poor, sleep-deprived body, nudging her awake and wanting her attention. Hearing her tell stories about her childhood was my favorite kind of attention. Family stories felt more like destiny than fairy tales and fables. The best ones were told at night in bedrooms lit only by the artificial sky glow from outside.

Born in 1950, I imagined Mom’s whole childhood in black-and-white. The simple contrast seemed to suit her life on the farm. I snuggled up to Mom as she shared stories sometimes last told to her only friend, the family cow, before she was sent away for slaughter. As Mom’s voice resurrected decades-old memories, she became my age again, making me feel even more “one in the same” with her.

Granted, I never had anywhere near the hardness of life as Mom. And with gratitude, I knew this. The differences in our lives made hers all the more interesting and sad. I never had to harvest tobacco in the summer or sleep beside my sibling, seeing our breath during cold Wisconsin nights. I had a doctor, a dentist, and even a dance teacher, while Mom had none. And though I often felt odd-like at school (doesn’t everyone?), I’d never been ostracized for smelling different or having a parent in jail or rumors of hanky-panky happenings at home.

Small-town 1950s life had major downsides to anyone or family on the outside of whatever those on the inside said was okay. Some families could become excluded after something happened. But for other families, no happening was needed to be excluded. The one Black family and one Jewish family in the town were each excluded without any reason or rumor. It’s not part of my family’s story, but it’s an important difference to acknowledge because it is consequentially different.

Hearing Mom’s little-girl self made me want to be her friend—because she was lonely and because I liked her. Plus, I wondered the same things she did: Why are some people so needlessly mean and others so caring and kind, even to complete strangers? Why do good people do bad things, sometimes to the people they love most? And why are people so often unfairly labeled in ways that are life-changing?

Earning your keep

Script-flipping often happens by events that are unwanted, unsuspecting, and unequivocally permanent. In 1965, Mom’s world that I imagined turned Kodachrome color just as her whole life changed in an instant flash.

Mom’s dad suddenly died. Her mom (my Grandma Odessa) had left four years earlier and had no means or health by that time to take custody of Mom and her siblings. As was common then, leaving your husband (no matter the reason) meant losing everything, including your kids. So Mom spent her remaining high school years as a “ward of the state” (something sounds so wrong in that phrase).

As Mom entered the foster system, living in three different homes, all the complex ways people can be shaped her path. Some people were too scared, busy, or minding-their-own to help. Others were extraordinarily generous or simply inhumane.

After Mom’s first wonderfully kind foster mom was hospitalized,1 she and her younger sister were sent to a new home, moving in with a married couple and their two daughters. Stories of this second foster home sounded sort of like the centuries-old Cinderella saga. That story stayed with me, along with the words “better earn your keep.”2

Being mistrustful of Mom spending time with her sister, the wicked woman kept them apart and then asked for them to be separated, leaving Mom alone in her cold, cruel care.

Cruelty can happen without ever being touched, and without ever having “proof.” Mom was told she had to walk to school behind their daughters. When Mom spoke, they pretended not to hear her. And Mom wasn’t trusted or allowed bathroom time without constant knocks or intrusions. No wonder Mom suffered from diverticulitis then, a condition she still has today. Can a person ever feel totally safe and okay after an experience like that?

Mom found whatever way to hold on to herself, hiding her clipped fingernails underneath her pillow when they made her clip them off—they were hers and hers to keep. On Mom’s 15th birthday, she was unexpectedly left home alone. She was given a gift: clothing fabric. Instead of making new clothes for herself, she ran away, on foot, walking miles.

When you feel like you’re in a sinking boat, a chance for better is better than no chance at all.

Seeing my destiny

I took this picture last fall while chaperoning a field trip to a pumpkin farm, located along the same stretch of highway Mom walked along to go back to her hometown after escaping the mean foster home. I didn’t grow up in Wisconsin, and when we came back when I was a kid, we only went to Dad’s hometown.

Mom never shared a nostalgia to go back home and I always understood why. So being there on that unusually warm October day, looking through the lattice layer of clouds, seeing the sun from a place Mom would’ve walked past, I felt a sameness with Mom like I’d felt my whole life. Feelings of hope from a sun not too bright to see shifted to heaviness in my heart, out of sync with the squeals and screams from the school-aged kids running in swirls.

I felt that sameness as a teen and thought for sure our destinies were intertwined when my stepdad was in the ICU and expected to die, the exact age she was when her dad died. Knowing what it’s like to never get the chance to say goodbye, Mom had my brothers and me write goodbye letters to share with him. Maybe he’d hear, or maybe not. Either way, our feelings would come out, and out was almost always better than stuck inside.

But at 14, my feelings were all mixed up in an Inside Out sort of way. All I knew is that I wanted to flip the script—on everything. I had an Appetite for Destruction with a Metallica mood to match. “I miss your old cheerleader self,” Mom would say, and I hated that preppy and perfecting version of myself, wanting her gone even more.

I pasted over my flowery bedroom walls with posters of dudes in faux leather pants and hair so big it went off the page. The few girl glam bands blended in that metal wall of fame in a gender-blurring way I thought was interesting, more so than the cheerleader-jock contrast that bored me by then. Plus, I was so annoyed that Mom idealized my old group as wholesome sweet and better than my new one. There are many sides to every group, and no group is totally safe3.

The voices and faces of every late 80s hairband filled my head in my bedroom, a refuge from the chaos and sadness outside. Even hard-core metal music like Megadeth and Slayer soothed me. I prayed Gene would make it through, but then felt guilty: Was it really him I was worried about, or was it what would happen to me?

Sinking-boat feeling

Dad took this picture of me that same spring. The weather was warm so we ate at our usual forest preserve spot. Dad’s condo food stock usually consisted of cans of beer, cans of soup, and a collection of condiments. I never remember eating in his home.

Since the divorce four years earlier, Dad lived in Lombard, another Chicago suburb not too far away. He was gearing up to move to Mankato, Minnesota, following a job transfer that summer. I didn’t know what that’d mean, or even how I felt. My feelings for Dad felt unsatisfyingly complicated.

The threat of Dad retaking custody had lingered after my parents’ divorce, but the threat had been building in the past year. The escalation of Gene binge drinking, money stresses, and health crises could serve as evidence of Mom’s unfitness for keeping us in her care. If Gene died, the stress would be way worse, and maybe Mom would be sent away, like her foster mom had or like my dad’s mom did.

A sinking-boat feeling was setting in while I began preparing for a time when I might have to hedge my bets. Leave. Just go. Somewhere. Because there was one place I knew I could never live: My Grandma Marie’s Lysolized Castle, which is where I knew I’d be sent if Mom lost custody.

Dad liked being a dad, but not like an every damn day “it’s all on you” dad. Though I loved Grandma Marie and knew she could provide a physically safe space, I could barely get by a few weeks there in the summer and knew it’d never be a home.

In some ways, we were too much alike: strong-willed. (Commonality does not necessarily create good chemistry.) And in other ways, she was so different from Mom: harsh and cold. I’d choose emotional safety over the physical kind in almost every circumstance. Because really, feelings can feel just as painful and more.

I wrote about those visits to my grandma’s house here:

I promised myself I’d run away if I ever got sent to live there. I watched Poison’s “Fallen Angel” music video, rewinding and replaying, seeing the girl from the Midwest get on the bus, the one played by Brett Michael’s then-girlfriend, Susie Hatton. She had “her whole life packed in a suitcase by her feet.” And she was headed to LA to “roll the dice of her life.”

The more I watched it, the more I wondered, “Maybe I should roll the dice too?” No, not for the chance to become famous. I had some sense of realism, and a houseful of my brothers’ friends to tell me everything about my body and how it “ranked.” Unfiltered and unsolicited honesty sucked. But sometimes, their straightforwardness seemed simpler to read than conversations with other girls also socialized to be Cinderella no-ego “nice” all the time, which isn’t possible (even for my mom).

Open, honest, and respectful relationships are so refreshing (and worth the work). It only took me several decades to figure this out. But I did have some self-awareness back then. I knew I didn’t have the goods to be model material — no matter how many creepy guys and “photographers” later told me I did, along with my friends.

“But maybe, just maybe,” I thought, “I have enough of something to find some place to be, earning my keep.” And more importantly, “Someone to be with, so I never have to be alone.”

At 14 going on 15, my body started mattering in new ways that meant something. Was it good or bad? I couldn’t tell. It reminds me how one of my babies went through a phase where they made a scrunched up funny-looking face at strangers. For months, he’d make the same face in line at the grocery store or at school pickup. He seemed so surprised by how his facial expression could cause strangers to react in different ways.

Still a kid or something else

The changing reactions to my changing body on some level fascinated me. But when it came from adults, it felt scary. Once puberty hit, girls started getting hit on by men sometimes decades older, in a very unpredictable way. Take the two bus drivers in my neighborhood: two middle-aged men who looked alike but one saw 14-year-olds as kids, and the other saw opportunities.

My bus driver would look you up and down, winking in approval as he told you how nice you looked. After seeing me put out my half-lit cigarette before climbing onto the bus, he offered to let me smoke the rest on board, smiling with eyes saying, just between you and me. To get away from him—and be by my friends—I tried switching routes.

I turned to my crafty friend for help changing the bus route on my school ID. She knew how to turn cutoff Barbie doll hair into wearable extensions and make homemade fake nails that almost looked real (from a distance). That bus driver looked at the ID and then back at me. He called me a bratty kid, tossed it back, and warned me not try shenanigans like that again.

Nothing was a given. This I knew. But some chances were worth taking. And some were worth giving your all. Like Cinderella, my body might make me matter to someone who would protect me. But also like her, I felt blamed and targeted, sometimes missing the days when my body was mine alone, and left alone.

My urge to run away was soon quelled by Gene coming home from the ICU. The intense relief that he made it through was shadowed by knowing anything ahead would be borrowed time. Still, it was a relief and a gift we’d gladly take.

Mom grew busier working to keep the lights on and keep up with Gene’s complex and costly medical care. Had I been 10 at the time, I would have painstakingly been as perfect as possible to make life easier for Mom. But at almost 15, my brain was not thinking about Mom. I wasn’t even thinking that much about friends.

Girl drama between friends bored me. Plus, my hormones drew me in the opposite direction. I wanted their attention. I wanted an audience. But mostly, I wanted an audience of one—the best kind in my book. The one you can lay in the dark with sharing stories that become each others. I loved my cat and my God. Still, I needed more. Yes, I’m needy. And no, I’m not sorry for being so.

Cinderella moment

That summer, my braces came off and I felt instantly older. My Cinderella moment came at the hairband’s concert. After the concert I waited near the entrance with my two friends, trying to spot Mom’s powder blue parent-pick-up Dodge Caravan. A scruffy, long-mulleted, wiry roadie guy approached us. With a Led Zeppelin look of the late 70s, he was probably late 20s I guessed.

“Do you wanna go backstage and meet the band?” he asked me, holding up a large red, round backstage pass sticker. “Can we all go?” I asked. “No, just you,” he answered, placing an awkward decision in front of me.

I’m often cautious because I tend to overthink. Plus, bad things from stories, movies, and real life stay stuck in my head. But when it came to split-second decisions, my teen brain was full-on in for most things, which put me in a perpetual state of doing something and then regretting it. So I went, knowing the girls I was with might be mad, but also knowing, if not this then something else. Girls were so fickle like that, I reminded myself.

As we walked through the nearly empty stadium, I felt a safety in the wide openness even as he felt me up while placing the sticker pass on my chest. My whole life, I’ve always had a delayed reaction to everything. So something like that didn’t even register as anything at the time.

He dropped me off at the end of a line leading up to the lead singer, Tom Keifer, who was signing autographs and chatting with fans. I stood there taking the atmosphere in, feeling almost drunken but without the dizzy. But no, it wasn’t because I was fangirling over the superstar’s bare-chested sex appeal and barely-there hot pants.

I never understood celebrity obsession. Though he did look even more fantastical in person. And how could I not get some gratification from the equalizing aspect of seeing grown men having to deal with all the trappings of objectified sex appeal: hair, makeup, uncomfortable clothes that show everything even on days you don’t feel showy, and clunky, grippy accessories that pull in odd ways and weigh you down?

Instead, I was drunk by the energy in the room. I didn’t have the confidence the people there had, but wished I did. I imagined how cool it’d be to flip the script, turning “Pick me, pick me” into “Take it or leave it.” You get to take the chance without risking the chance you’ll lose? You win either way—how utterly brilliant.

Groupie girl chemistry

Soon, another teen girl standing in line struck up a conversation. Quickly, I learned she knew what she was doing. I studied her hair so high, bustier so low, and skirt as short as short shorts get. Looking down at my tee, cutoffs, and Keds, I suddenly felt so school-age drab. She was colorful cool in a glam metal way that seemed funner and more playful than my Black Sabbath sad.

As she chatted at a racing pace, I learned why she seemed so at home backstage, given her young age. She was there with her dad, an ex-roadie. She pointed him out across the room where he was talking to another similarly-looking man his age. And her nearly same-age sister was also with her, standing quietly at her side.

The quiet sister's dulled demeanor seemed out of sync with the personality you might expect from her Malibu Barbie, popular-girl appearance. She wore a tube top, miniskirt, and max-high heels. She seemed less like someone who’d become a friend. What is it about chemistry that tells you things like that?

Chemistry is real in relationships. A hairstylist recently told me about how tough online dating was without being able to tell if there’s chemistry. After giving up on the apps, she met her partner at a karaoke night. There’s something in presence and space that can’t come across online. Um yeah, she’s my age. So maybe that’s why? Finding chemistry with a total stranger doesn’t seem like something young people I know are open to. (Though honestly, I think they would be if they knew other people were.)

It was clear sister number one was the thought leader of the two, driving the conversation and direction. Her slightly crazed “dare me” bravado and hell-yeah conviction added an outsized contribution to the overall vibe in the room. And she had an earthiness that made her seem immune to the passive-aggressive girl-drama so annoyingly familiar in same-gender friendships I’d experienced and seen. I felt an instant chemistry with her. We exchanged numbers and addresses that night.

A few weeks later she sent me the photo she’d taken of me with the singer and included a long letter. By then, I’d started dating the a guy down the street. I found my audience of one and didn’t have time to think about anything else. I stuffed it in a drawer and forgot about it.

Fast forward several months and that sinking-boat feeling started setting in, weighed down by a newly placed bright red scarlet letter ‘S’ I’d been branded with.

I pulled out the groupie girl’s phone number. When you have a sinking-boat feeling, a chance for better is better than no chance at all. To be continued …

Every risk-taking harm I experienced happened at times I felt emotionally unsafe. And the same is true for most everyone I know. Helping everyone feel safe, welcomed, and included is a gift for everyone that needs to continually be given. Some lessons I don’t need to relearn with each rehashed cultural backlash.

Mom’s first foster parent was an amazing woman with a sensibility ahead of her time. She became estranged from her own children after divorce. She took Mom under her wings and made a lasting difference. Mom stayed in touch, regularly visiting her through her final years. Helping is healing, oftentimes both ways.

I grew up hearing Mom say, “Better earn your keep,” and I started saying the same to myself. Those words weren’t mine. I had no need for them. Why was I telling myself that into my thirties as I scrubbed my home’s floors Mop & Glo pristine clean? Worth isn’t earned or given. That phrase is going down with this ship.

Growing up on the outside looking in, Mom imagined the inside as a “happily ever after” place to be. She wanted that for me. But being on the inside isn’t perfect. Mom later learned that even some kids from “good” homes where she grew up had bad things happen too. Empathy for everyone is ever-important.

And yes, I overused the sinking-boat analogy. Infinity Song’s mesmerizing “Sinking Boat” was in my head while writing this post.

That Cinderella (the band) story is wild 😅. I went to a few metal band concerts in the 80s myself. Can't believe my mom dropped me off at that age and drove away.